Why were the Knights Templar so interested in Harran, one of the oldest cities in the world?

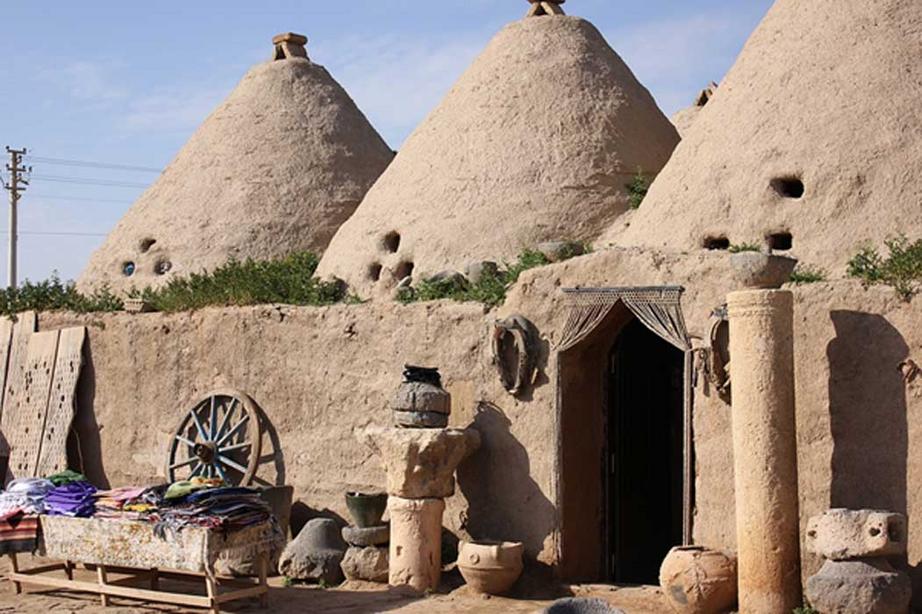

Harran is one of the oldest cities in the World. Located in southern Turkey, a remarkable feature of this ancient place is its beehive-shaped adobe houses, built entirely of mud without any wood. Their design makes them cool inside and is thought to have been unchanged for at least 3,000 years. Some were still in use as dwellings until the 1980s. Harran dates back to at least the Early Bronze Age, to sometime in the 3rd millennium BC.

Dome Urfa Harran

Dome Urfa Harran

Renown as a point on the Silk Road, there are many references to this ancient place in the Bible and, for example, its trade with the Phoenician city Tyre in ‘choice garments, in clothes of blue and embroidered work, and in carpets of colored stuff, bound with cord and made secure’ (Ezekiel 27:23-24). It is perhaps most famous as the city of Abraham. His birthplace, Sanliurfa, is close by and Harran is the place where his father Terah went to die. My own interest in this city is not, however, in its Biblical connections, fascinating though they are, but in its more esoteric history.

Harran beehive houses

Harran beehive houses

The Christian Interest in Harran and the Ancient Kingdom of Edessa

Harran’s close neighbor, Sanliurfa, holds a clue to this hidden aspect. Sanliurfa has undergone many transformations over the millennia. Most curiously, in the 12th century, when Sanliurfa was a Christian kingdom that went by the name of Edessa, it attracted the attention of the Knights Templar. There seems to be some significance in St Bernard of Clairvaux, and not the Pope, preaching the Second Crusade at Vezelay in Eastern France, not in order to defend Jerusalem but to rescue Edessa after its capture by the Seljuk Turks in 1145.

Christ Embracing St Bernard by Francisco Ribalta (circa 1625)

Christ Embracing St Bernard by Francisco Ribalta (circa 1625)

The question is, why? Why did St Bernard, who was responsible for helping to create the Knights Templar, take such an interest in this land-locked city-state which, as writer Adrian Gilbert points out, was of no strategic importance on the wrong side of the Euphrates? (Adrian Gilbert Magi – the Quest for a Secret Tradition, Bloomsbury, London, 1996 p191) It was quite a military undertaking after all, and not an obvious destination.

Trulli in Harran

Trulli in Harran

Maybe the Knights Templar knew that Edessa could have been the original ‘Ur of the Chaldees’; the place where the Chaldean Magi had spent time. In the 1920s, Sir Leonard Woolley claimed that the ‘Ur of the Chaldees’ was his excavation of the city of Ur in southern Iraq. What he found was spectacular and extensive: huge quantities of artifacts dating back three thousand years, and much gold, including a beautiful golden sculpture of a ram caught in a thicket. Many of his finds are on display in the British Museum. But important though his find was, I am not convinced that this was the Ur of the Bible. ‘Ur’ is a common word found in ancient times as it has the meaning of ‘foundation’ and can be found in the name of Jerusalem – ‘Uru-shalom’ – meaning ‘place of peace’. It makes more sense that the Chaldean Ur was further north, not least as Abraham makes reference to his conflicts with the Hittites who were based in central Turkey.

The famous Ram in the Thicket found in the Great Death Pit at UR Gold Silver Lapis Lazuli Shell 2600 BC

The famous Ram in the Thicket found in the Great Death Pit at UR Gold Silver Lapis Lazuli Shell 2600 BC

Hidden Knowledge in Harran?

The Chaldean magi, an elite of wise men, skilled in the arts of divination, had taken refuge in the remains of the Hittite empire in central Turkey at least a thousand years before the Knights Templar arrived and it is possible that something remained of their occult knowledge in the area. But it is just as likely that the real focus of the Templar attention was Harran itself.

It is important to reflect at this point on what might have been the genuine mission of the Knights Templar. There is no doubt that St Bernard played a key role in creating the cover story that this select group of religiously inspired crusaders existed to protect the routes to Jerusalem. But given the low numbers of Templars, at least to begin with, this explanation does not make sense. What is more plausible is that they had a presence in the Near East because, after the First Crusade in 1097, St Bernard and others from the Court of Burgundy became aware of occult knowledge contained in a body of writings known as the Corpus Hermeticum considered to be ‘older than Noah’ having been composed by Hermes Trismegistus and therefore of great interest. And one group of people who knew a lot about the Hermetica was the Sabians, who at the time of the Crusades lived in Harran.

What made Harran unusual in the 12th century was that it was not Jewish, Islamic or Christian. Its main temple, eventually destroyed by the Mongols in 1259, was dedicated to the Mesopotamian Moon god, Sin. It was also famous as a center of alchemy, as practiced by the Sabians who regarded Hermes as the founder of their school.

Worship of the Moon God. Cylinder-seal of Khashkhamer, patesi of Ishkun-Sin

Worship of the Moon God. Cylinder-seal of Khashkhamer, patesi of Ishkun-Sin

A Sabian Sanctuary

The Sabians’ distinctive form of alchemy focused on metals, especially copper, and minerals, rather than gold. In the view of some writers, this distinction indicates a very early tradition, possibly going back to 1200 BC when copper was the chief metal (Jack Lindsay The Origins of Alchemy in Graeco-Roman Egypt, Frederick Muller, London, 1970). There is little doubt that the Sabians’ beliefs and practices date back into ancient times and that they had strong links with Egypt. Indeed, it is possible that the name ‘Sabian’ derives from the ancient Egyptian word for star, sba, and they may have been ancient refugees from Egypt.

The Sabians could have been the last remnants of Egyptian priesthood which mostly disappeared from Egypt in the 4th century when Romano-Christians destroyed what was left of Egyptian temples. As a result of that persecution, they may have found their way up the trade routes to Harran on the northern Euphrates where they felt safe enough.

Hermes and Athena by Bartholomeus Spranger, 1585

Hermes and Athena by Bartholomeus Spranger, 1585

What kept the Sabians safe and allowed them to continue with their practices was a reference to them in the Koran. The Koran acknowledged that the Sabians were of the religion of Noah and therefore accorded them respect. The precariousness of their existence is, however, recorded in the story of the Caliph of Baghdad who passed through Harran in 830 AD. He wanted to know if those who dressed differently were ‘people of the book’ (i.e. the Koran or Bible). Fortunately, he accepted the response that the Sabians’ ‘book’ was the Hermetica, their prophet was Hermes and they were the Sabians referred to in the Koran and so they were spared death as infidel.

Little did the Caliph realize how much the Sabians had contributed to his own culture, Sabians having helped to found the city of Baghdad in 762 AD and turn it into a great seat of learning. The Sabians were a great ‘conduit for the transmission of ancient wisdom to the Arabs, especially to the Sufi and the Druze (Adrian Gilbert op cit,1996, p70). It was a Sufi alchemist by the name of Jabir ibn Hayyam who had in his possession one of the oldest copies of the most famous Hermetic texts, the Emerald Tablet, and who wrote the magical tales of a Thousand and One Nights. He was skilled in mathematics, medicine and other sciences and was keen on disseminating knowledge of the Pythagorean principles of number (Baigent & Leigh - The Elixir & The Stone, Viking, London, 1997 p41).

Above all, it is thanks to the Sabians, and to the city of Harran, that so much knowledge relating to ancient civilization, to the Egyptians and others, was preserved throughout the Dark Ages and from which we can now once again benefit.