Through the twelve chambers of hell

...The afterlife in ancient Egypt

Death, the ancient Egyptians believed, was not the end of our struggles. They believed in an afterlife and that the worthy would go on to paradise, but their dead didn’t simply pass over to the other side. If they wanted eternal life, they would have to fight for it.

The souls of dead Egyptians had to battle their way through the twelve chambers of hell, overcoming demons and monsters, crossing over lakes of fire, and finding their way past gates guarded by fire-breathing serpents. The path through the afterlife was violent, brutal, and dangerous. They could be killed in hell, and a death there meant an eternity in oblivion.

If they made it through unscathed, they would meet their judgement day. They would stand trial before the gods, who weigh their hearts against the weight of a feather. The worthy might go on to paradise, or even become a god – but the unworthy would have their hearts cast to the demons, torn to shreds, and devoured.

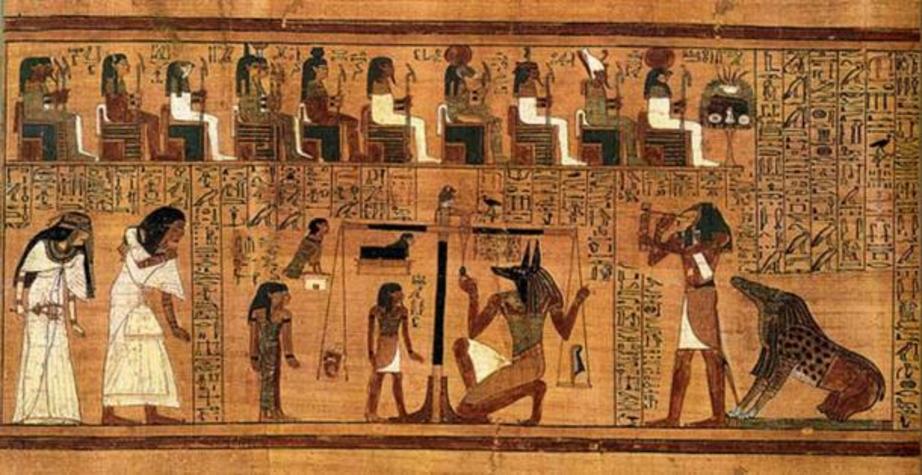

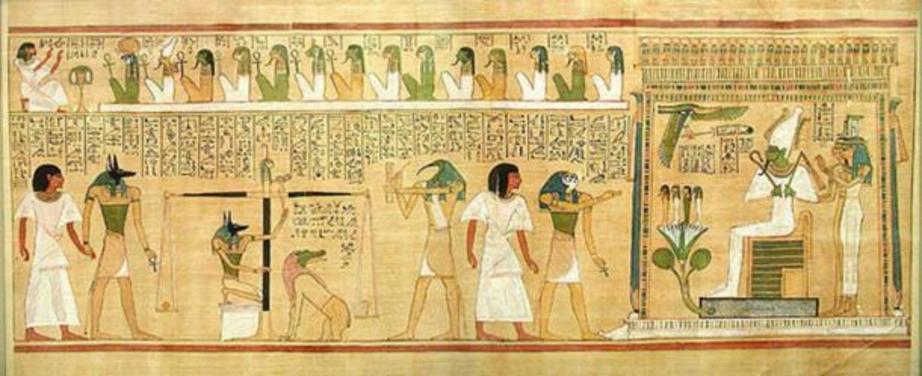

The Weighing of the Heart from the Book of the Dead of Ani. At left, Ani and his wife Tutu enter the assemblage of gods. At center, Anubis weighs Ani's heart against the feather of Maat. At right, the monster Ammut, who will devour Ani's soul if he is unworthy, awaits the verdict, while the god Thoth prepares to record it. On top, gods are acting as judges. (Public Domain)

The Egyptian vision of the afterlife was incredibly complex. We’ve seen the decaying remains of their fixation on death: the massive pyramid tombs that dwarfed their cities and the mummified bodies buried inside. But these were more than just monuments to the vanity of kings – they were gateways that got them ready for the afterlife, where priests prepared their souls for an incredible journey unlike anything they’d experienced in life.

A Soul Split in Two

When the body died, the Egyptians believed, two parts of the soul would split apart. The life essence that made up a man’s spark and energy would get up and move, free to roam around its tomb and to make its journey up into the afterlife. But the other part of the soul, the part that carried the personality, was left behind, trapped in the lifeless and motionless body that stayed on the earth.

The dead’s only hope for eternal life and a reunited soul was to travel through hell and face judgement. If the essence of their soul could make its way through Duat, the Egyptian netherworld, and pass judgement before the gods, their souls would be reunited – but this was no simple journey, and the clock was ticking. If the body crumbled into decay before their essence made it through the netherworld, the part of the soul trapped inside would die. It would all be for nothing.

Mummy of an upper-class Egyptian male from the Saite period. (Keith Schengili-Roberts/CC BY SA 2.5)

Preserving A Dying Soul

Egyptians were mummified to keep their souls alive. Their bodies needed to stay preserved or else their chance at eternal life would be lost. And so Egyptian embalmers would pull out their vital organs and their brains, leaving only the heart, the home of the soul, inside. They would drain their liquids until their bodies were completely dry, leaving them in a state that could be preserved for thousands of years.

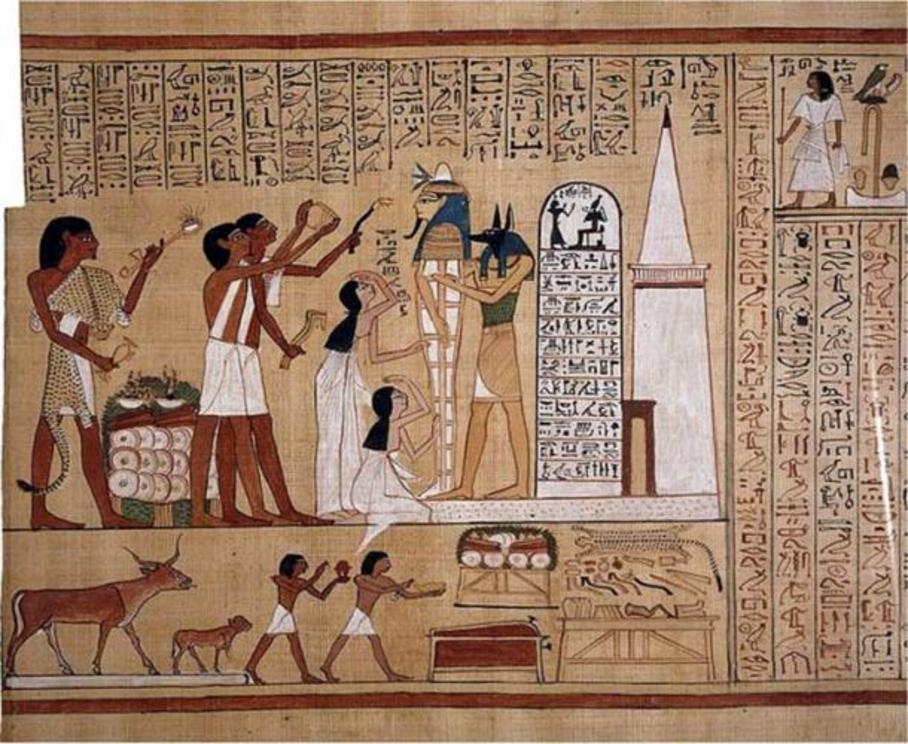

Even after death, though, the soul trapped inside the body needed to eat. It could still starve – and so a sorcerer would have to call on the gods to open its own mouth. After the body was buried, priests would perform a long and complicated ritual, pulling open the mouth on the statue made in the image of the dead, begging the gods to let them eat, and leaving sacrificed animals at its foot so that the soul could feed.

The mummy of Hunefer is shown supported by the god Anubis (or a priest wearing a jackal mask). Hunefer's wife and daughter mourn and three priests perform rituals including the Opening of the Mouth ritual. The lower scene has a table bearing the various implements needed for the ritual and animals being led to sacrifice. (Public Domain)

The rituals gave them a fighting chance at eternal life, but this procedure was expensive. The pharaohs and the wealthy could get a tomb and an embalmer to help them earn their second life, but there was no protection offered to the souls of the poor. Their only option was to carry their dead out into the desert and bury them in a shallow grave in the hopes that the dry air would dehydrate their bodies long enough to reach paradise.

Crossing the River in the Sky

While one part of the soul stayed behind in the decaying body, the essence of the soul had to make its journey through the netherworld. But this wouldn’t be an easy trip.

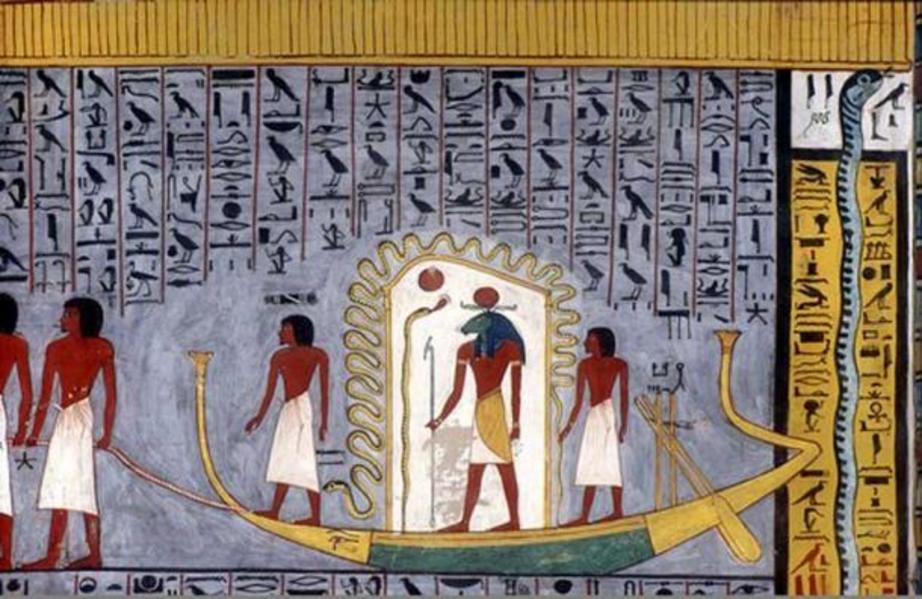

Between earth and the netherworld, the Egyptians believed, there was a great river in the sky that even the gods couldn’t pass. The only person who could pass it was the ferryman of the gods, a creature with eyes on the back of his head. The ferryman, though, wouldn’t always help. Sometimes, he had to be persuaded. And sometimes, he had to be threatened.

When a pharaoh died, sorcerers would spend days casting magic spells to help his soul make it into the netherworld. These would be please to the divine – and sometimes threats. When the Pharaoh Unas died, his sorcerers ordered the ferryman to take him across, threatening, “If you fail to ferry Unas, he will leap and sit on the wing of Thoth,” warning him that, if he did no obey, he would face the wrath of a god.

Ra traveling through the underworld in his barque, from the copy of the Book of Gates in the tomb of Ramses I (KV16). (Public Domain)

Passing Through the Twelve Chambers

The ferry, though, would take them through Duat, a land full of gods, demons, and monsters, many of which were out to kill the soul that tried to pass through. These creatures would prey on the souls of the dead, who had to fight them off with magic and weapons, and so the dead Egyptians were often buried with spells and amulets to help them stay in the netherworlds.

To make their way through Duat, they would pass through twelve impenetrable gates lined with sharp spears and guarded by snakes who breathed venom and fire. The only way to pass through was to say the names of the guardians. Many kings would be buried with these names, lest they forget.

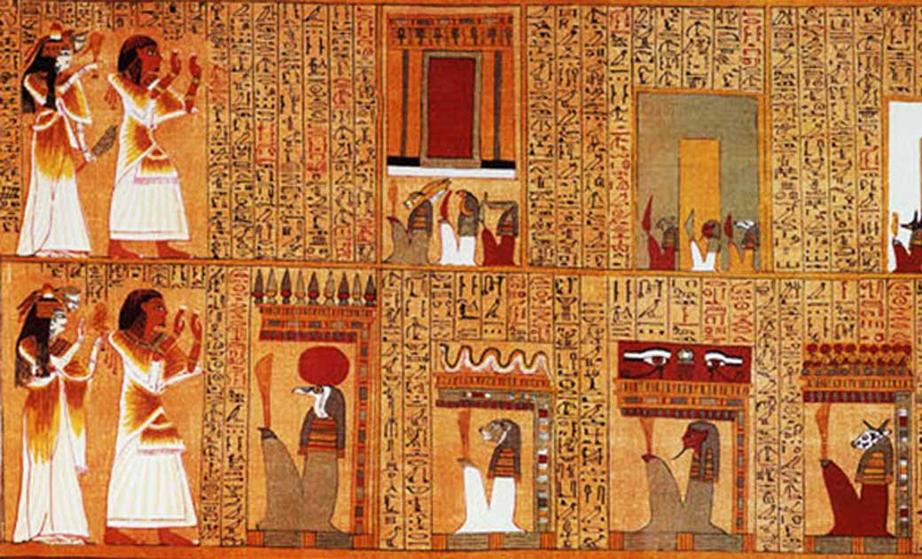

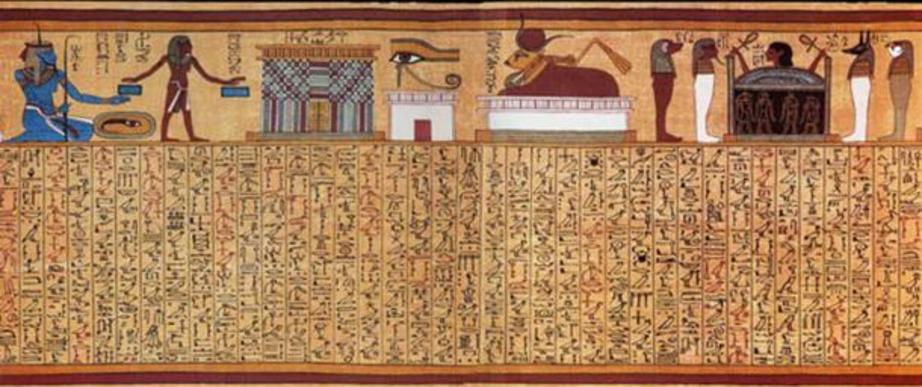

Book of the Dead spell 17 from the Papyrus of Ani. (Public Domain)

Some were even buried with a map of hell. It would show a world not unlike Egypt, but dotted with supernatural wonders. Alongside caverns and deserts, a voyager travelling through Duat was promised to see forests of turquoise trees and lakes of fire.

Threatening the Gods

For all the terrors of Duat, though, the pharaohs themselves were often the most horrifying things there. During the Old Kingdom of Egypt, many kings would threaten the gods before their deaths, warning them that they were coming into their domain – and promising to butcher them and cannibalize their bodies.

Some pharaohs left messages in their tombs, warning the gods that a king is coming who “feeds on gods.” One promised that three Egyptian gods were going to tie their brothers down and tear out their entrails so the pharaoh could cook them and eat them.

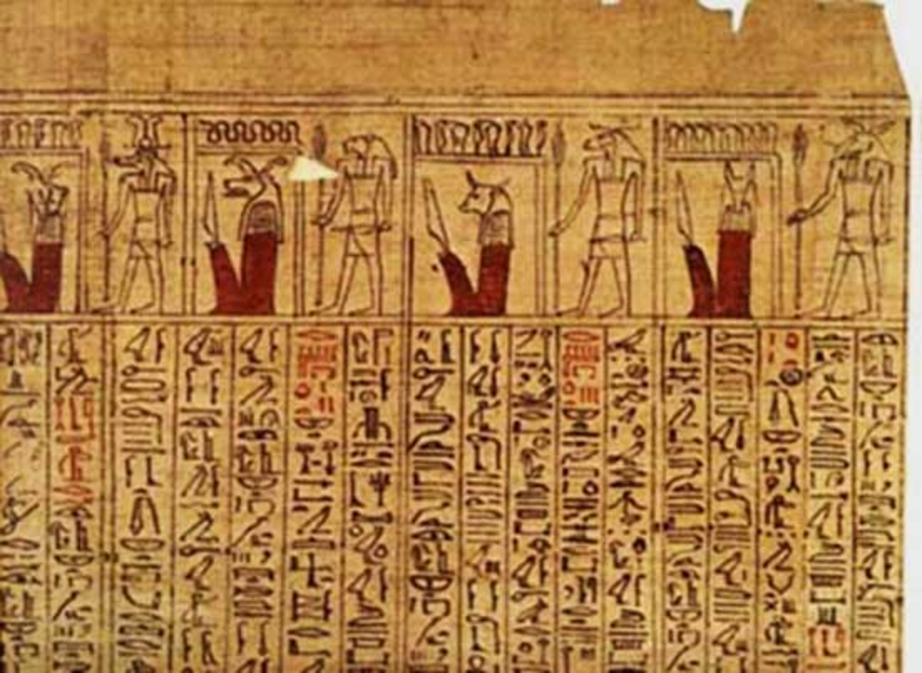

Guardian demons of Spell 145 of the Book of the Dead. (Rita Lucarelli/UCLA)

Eating a god would give the pharaohs the strength to make it through the netherworld. They could steal a gods’ divine powers and knowledge by taking a bite out of a minor deity – or, as one pharaoh promised, by devouring their heart, smashing their bones and sucking out their marrow.

The Judgment

If souls could make it through the twelve gates, they would arrive at the Kingdom of Osiris, the god the dead. Here they would have to plead that they had lived good and just lives by denying having committed a set of 42 sins. Then their hearts would be weighed against the feather of Ma’at, a symbol of goodness, to see if they were truly pure.

The innocent were reunited with the part of the soul left behind in the body. They would be granted eternal life and passage into paradise, where they would live with the gods in a land where the fields grew in an endless abundance.

Even here, though, a soul could meet its end. If the gods ruled you were wicked, your heart would be thrown to The Devourer, a creature that was part lion, part hippo and part crocodile. Then their souls would be cast into a pit of fire and they would be erased into oblivion.

The scribe Hunefer is conducted to the balance by jackal-headed Anubis, who also weighs the heart against the feather of truth. The ibis-headed Thoth records the result. Ammit, which is composed of the deadly crocodile, lion, and hippopotamus watches. In the next panel, showing the scene after the weighing, a triumphant Hunefer is presented by falcon-headed Horus to the shrine of the green-skinned Osiris accompanied by Isis and Nephthys. 14 gods are shown above as judges. (Public Domain)

An Eternity of Servitude

The journey to paradise, for the Egyptians, was no easy path, but it was far easier for a pharaoh than a common man. There was no equality in the afterlife. Even in paradise, a king would become a god, while a servant’s only reward would be to till a slightly higher grade of wheat.

This was actually a step up, though. In the early days of the Old Kingdom, Egyptian priests taught that only the pharaoh could enter paradise, while the rest had to stay in Duat forever, struggling to survive.

Even for the pharaoh, though, the path was never easy. Theirs was one of the most terrifying and challenging afterlives a culture could face. It was something a man might spend his whole life preparing to face. And, as the massive pyramids they left behind make clear, it was a fate the Egyptians truly believed awaited them on the other side.

Sphinx and Pyramids at The Giza Plateau (CC BY 2.0) , the moon, and clockworks (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Top Image: Detail of two ancient Egyptian 'gate spells'. On the top register, Ani and his wife face the ‘gates of the House of Osiris'. Below, they encounter the 'mysterious portals of the House of Osiris in the Field of Reeds'. All are guarded by unpleasant underworld protectors. Source: Public Domain