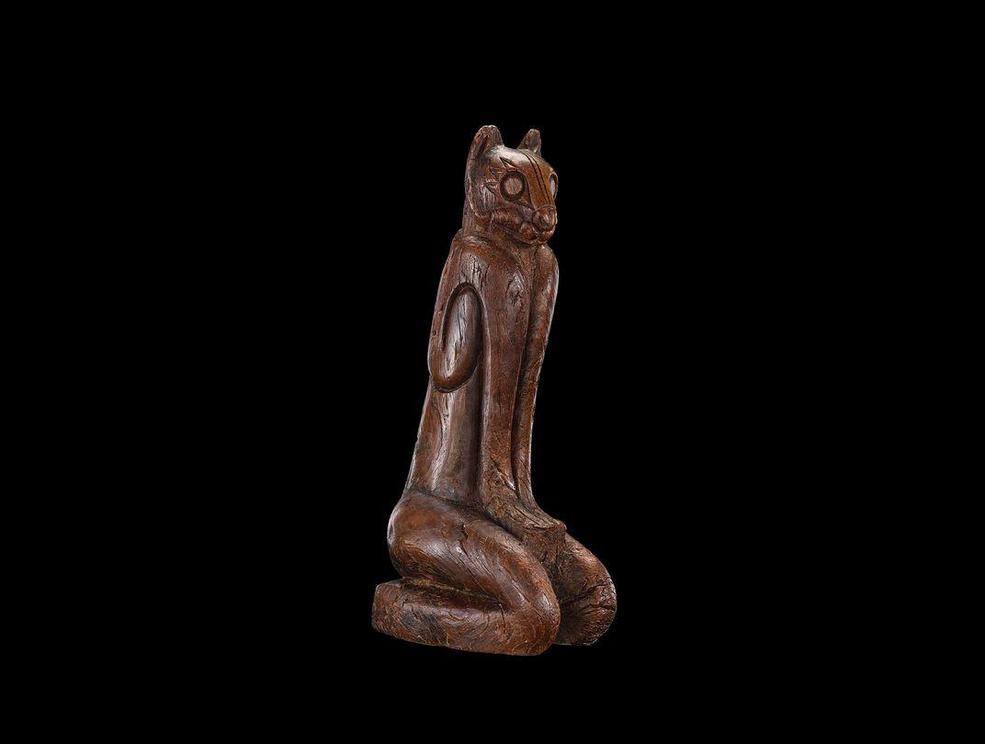

This hand-carved panther statuette embodies a lost civilization’s harmony with nature

Calusa Indians harnessed the bounty of Florida’s estuaries with respect and grace

The Key Marco Cat was unearthed at Marco Island off Florida’s southwestern shore in the late 19th century. (NMNH)

Standing no more than half a foot tall, the wooden statuette known as the Key Marco Cat is an enigmatic survivor of an American society lost to history. Its exact provenance is uncertain, but both the location of its discovery and the spiritual beliefs suggested by its appearance point to the Calusa Indians, a once-widespread people of the Gulf of Mexico whose distinctive culture collapsed in the wake of European contact.

Hewn from Florida cypress, the “cat” is in actuality only part feline—its head bears the pointy ears and big round eyes one would expect from a panther, but its long torso, rigid arms and folded legs are all suggestive of a human being.

The tragic history that underlies the wide eyes of the Key Marco Cat is a tale of a unique, vibrant society in perfect communion with its environment and the blundering conquerors whose poor health sealed that society’s fate.

As its sobriquet indicates, the Key Marco Cat was unearthed at Marco Island off Florida’s southwestern shore, in an astonishingly fruitful late-19th century archaeological dig commissioned by Civil War refugee William D. Collier and headed up by the Smithsonian’s Frank Hamilton Cushing.

In 1895, Collier and his wife operated a modest inn, hosting visitors eager to fish Marco’s rich waters. An avid gardener, Collier routinely tasked his employees with retrieving plant-friendly peat from the island’s swamps. In the process of doing so one day, one of Collier’s workers found his progress thwarted by a mass of solid objects hidden beneath the surface. Collier immediately set about getting an expert archaeologist on site.

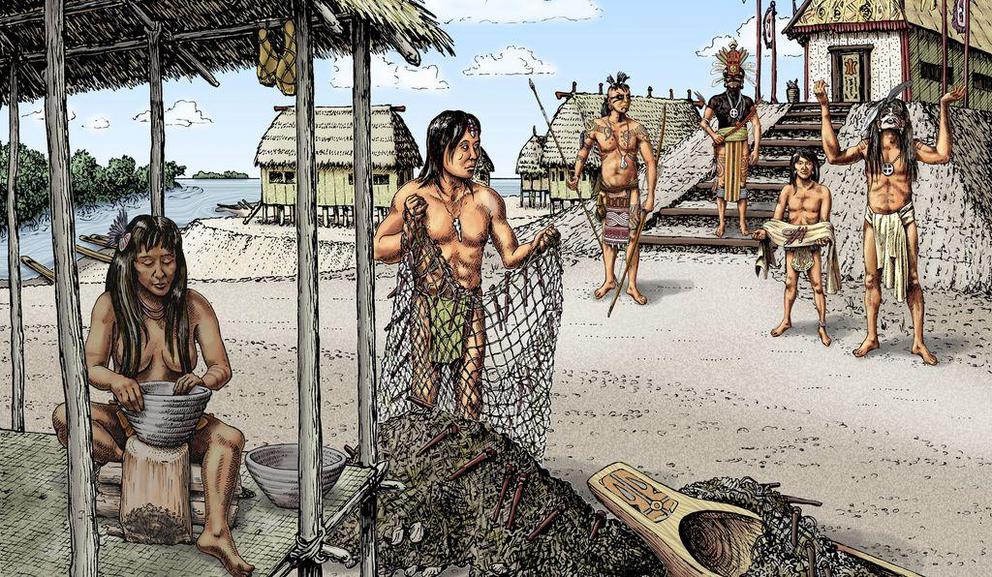

Between fishing and oyster harvesting, the Calusa were always well fed. Ever resourceful, they elevated their homes using middens of discarded shells. (Merald Clark; courtesy of the Marco Island Historical Society)

That expert was fated to be the fastidious Cushing, who was on sick leave from the Smithsonian Institution when some of the first Marco artifacts to reveal themselves—pierced shells and fishing netting—were brought to his attention. Thrilled at the prospect of deciphering the culture of a pre-Columbian people, a revitalized Cushing hurried off down the coast.

Environmental historian Jack E. Davis, in his 2018 Pulitzer-winning nonfiction epic The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, quotes Cushing’s logs directly, revealing that he “struck relics almost immediately” and considered his initial probe of the peat a “splendid success.” A ladle and wooden mask pulled from the muck spurred a more formal archaeological endeavor: the Pepper-Hearst Expedition, named for backers William Pepper (the founder of Penn’s Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology) and Phoebe Hearst (a prominent philanthropist and mother to William Randolph). Undertaken in 1896, this ambitious project surfaced approximately 1,000 unique artifacts from ancient Calusa society.

Among these was the entrancing anthropomorphic cat, which made its way into the collections of the Smithsonian Institution and rapidly became the object of anthropological fascination nationwide. Now, in 2018, the Key Marco cat is to return to its place of origin alongside an assortment of other tools and trinkets from Cushing’s dig for a special exhibition at the Marco Island Historical Museum. Since the late 1960s, Marco Island’s deep Native American history has been somewhat concealed by a veneer of glitz and tourist kitsch. The new Calusa exhibition, however, set to debut at the museum this November, will allow visitors a direct line of conversation with the people whose homes atop shell mounds and canoe-friendly canals far preceded today’s beachside resorts.

“They used their natural endowments from their surroundings to develop this very powerful chiefdom,” Jack E. Davis says of the Calusa in an interview. Ranging all along the southwest coast of Florida, the Calusa made full use of the Gulf of Mexico’s estuarine ecosystem. The confluence of freshwater and saltwater in the region’s ubiquitous estuaries made places like Marco Island hotbeds of subsurface activity. From dense oyster beds to meaty food fish like snapper and snook, the waters of the Gulf had endless gifts to offer.

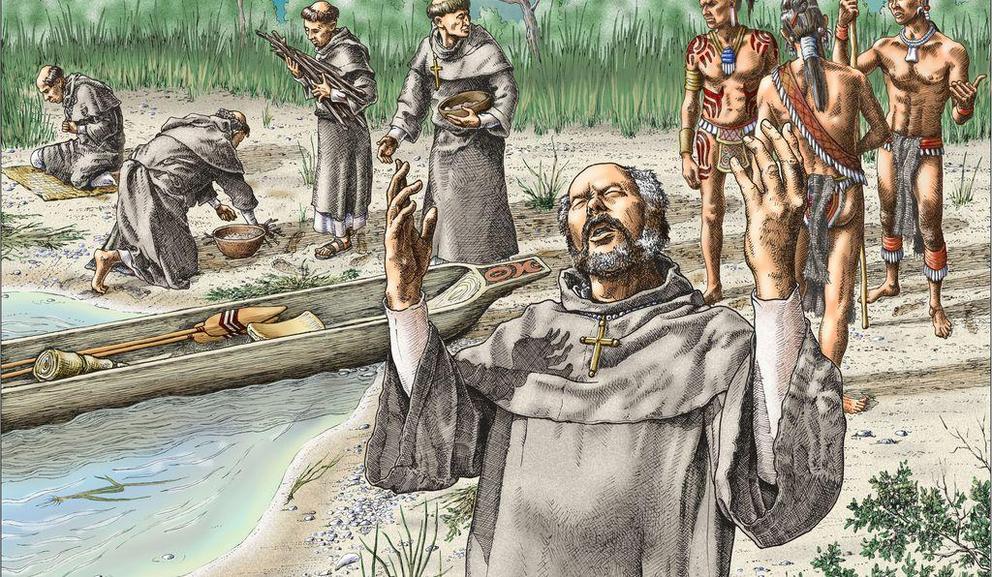

Unlike the brash explorers who sailed from Europe to lay claim to their land, the Calusa lived in respectful harmony with the wildlife all around them. (John Agnew; courtesy of the Marco Island Historical Society)

“What is unique about the Calusa compared with most other native peoples,” Davis says, “is that they were sedentary people who did not have agriculture.” The Calusa of Marco Island never feared food scarcity—the water always delivered. Fishing and oyster harvesting were so effortless that the Calusa could afford to focus on the cultivation of their culture, and explore surrounding waters in sail-trimmed canoes fashioned from hollowed cypress trees. “They were hunter-gatherers,” Davis says, “but they didn’t have to go anywhere. Everything was right there in those estuaries for them.”

The intimate relationship of the Calusa with their natural surroundings heavily informed their spiritual outlook. In The Gulf, Davis writes that “Life in all forms was a world of common spirits, of humans and animals.” The Calusa, like many other native peoples across north America, believed in a form of reincarnation, holding that one’s spirit took purchase in the body of an animal upon death. Animal spirits, by the same token, were transferred to fresh animal bodies when their present form expired. The half-man-half-beast Key Marco Cat stands as a striking testimony to the power of spiritual interplay among species.

This beautiful equilibrium was unceremoniously disrupted when Spanish conquistadors arrived in the early 16th century. The Calusa of Key Marco were not surprised when Juan Ponce de Léon approached their island in 1513—they had encountered itinerant Spaniards before, and even knew some of their language. Unafraid, the Calusa—much taller than the Spaniards by virtue of their hearty seafood diet—turned Ponce de Léon’s ships away, stunning the would-be colonists with a line of defense 80 canoes strong and an intimidating warning volley of arrows and poison darts.

Come 1521, Ponce de Léon was back, and eager for revenge. Davis notes that the Fountain of Youth fantasy we tend to associate with Ponce de Léon has little in common with reality. The explorer came back to the region in search of gold and territory—nothing so romantic as eternal life. Ironically, the voyage not only failed to confer immortality on him, but was directly responsible for his demise. On this occasion, a Calusa warrior’s dart, laced with the potent poison of the manchineel apple tree, pierced Ponce de Léon’s leg, sending him to the deck and ultimately to his grave. Once again, the Calusa had repelled the Spanish—and claimed the life of one of their most famous men.

In the years following Ponce de Léon's initial encounter with the Calusa, Spanish missionaries attempted to overwrite the native people's spiritual beliefs with Christian thought—to little avail. (Merald Clark; courtesy of the Marco Island Historical Society)

“These were tough folks,” Davis says of the Calusa. “They had communication networks, and they were aware of the Spanish before the Spanish arrived. So they were ready for them—and they were ready to resist. This is true with a lot of Gulf Coast natives.”

Even once the Spanish began making bloody inroads into mainland Florida, they remained completely oblivious to the natural cornucopia of the estuary ecosystem.

One striking illustration of this ignorance is the story of Pánfilo de Narváez, a conquistador noted for his cruelty and his bitter rivalry with Hernán Cortés who fell prey to a clever ambush by the Tocobaga tribe—coastal neighbors of the Calusa—after arriving unannounced in Tampa Bay. Cornered on the beach after an unproductive northward trek, Narváez and his men managed to jury-rig escape rafts using the trees all around them. Yet the notion of fishing seemingly never occurred to them—instead, they butchered and ate their own horses. Even after fleeing on their watercraft, Davis says, Narváez and his men refused to fish or harvest oysters. Their only food came from raids on whatever native settlements they chanced to encounter.

Starving and delirious, a subset of the original group of ill-starred warriors wound up reaching the shores of Texas. Their captain, the fearsome Narváez, was swept out to sea—and inevitable death—during an exhausted sleep on his raft. What conquistadors remained were so desperate they took to cannibalism, disregarding completely the fish thronging in the water.

Franklin Hamilton Cushing (left), backed by Phoebe Hearst (middle) and William Pepper (right), conducted a remarkably productive archaeological dig at Marco Island in 1896. (Merald Clark; courtesy of the Marco Island Historical Society)

“These explorers were from inland Spain,” Davis says, “and so they didn’t have much exposure to seafood.” But he acknowledges that that fact alone is insufficient to explain their boneheadedness in crisis. “My God, they end up eating each other!” In the unwillingness of the Spanish to respect the highly successful lifestyle of the Calusa and other estuarine Indians, Davis sees a historical question mark for the ages. “It’s one of those great ironies of history,” he says. “I think we’re totally dumbfounded.”

What ultimately spelled doom for the Calusa was not the military might of the Spanish so much as the vile contagions they brought with them from Europe. “It’s disease, it’s enslavement, and it’s warfare with other groups as their numbers are diminishing because of disease,” Davis summarizes.

The Calusa, formerly one of the Gulf region’s greatest powers, soon fell into obscurity. Some Calusa may have been absorbed into the Seminole people; others may have made it to Cuba. In any case, the blissful equilibrium of estuarine life on Marco Island ceased to exist. What had once been a formidable community and culture was now a ghost town of seashell mounds and disused watercourses.

Davis sees in the practices of the Calusa people a degree of humility and respect for nature from which we could all stand to learn. “The Calusa extolled wildlife in a way that we don’t, even when utilizing it for their own survival,” he says. “They lived in a much more stable relationship with the estuarine environment than does modern Western society. We’ve been very careless.”