The mysterious cocaine mummies

Evidence which shows that ancient Egyptians had already crossed the Atlantic 3,000 years ago, long before Columbus in 1492, comes not only from the mimicking of cultural traditions as seen in Peru and the Canary Islands where evidence of trepanning and mummification has been found, but from the actual Egyptian mummies themselves.

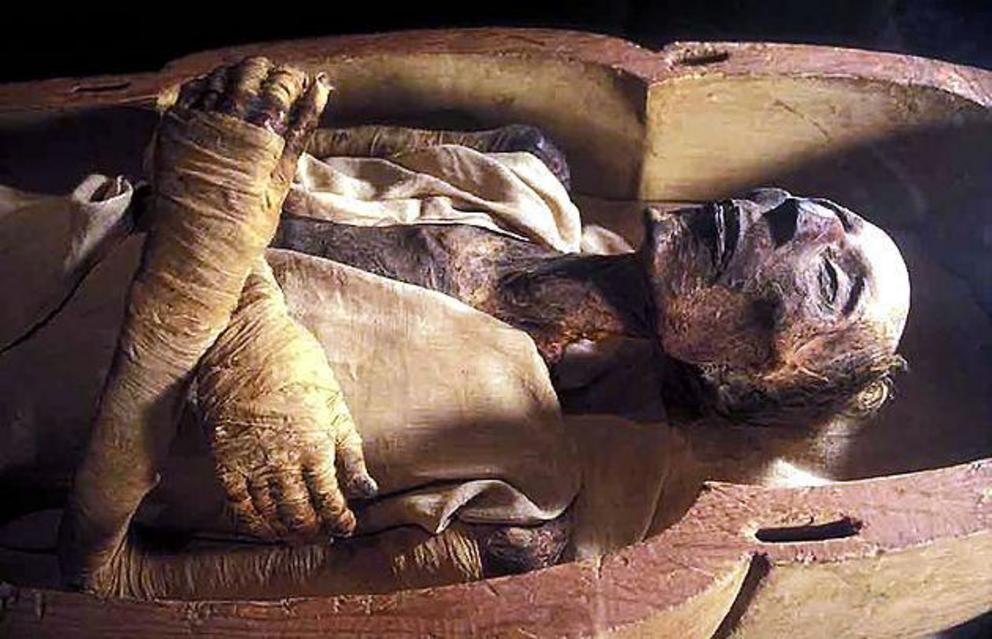

Incredibly, in 1976, Dr. Michelle Lescott from the Museum of Natural History in Paris received a sample from the mummified remains of Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses the Great to study. Using an electron microscope she discovered grains of tobacco clinging to the fibres of his bandages.

This initial discovery was berated by the authorities and her senior colleagues insisted that she had simply observed “contamination from modern sources”, maybe from some old archaeologist smoking a pipe in the vicinity, or perhaps she had found the traces of a workman’s sneeze? Tobacco first came to Europe from South America during the time of Columbus, 2700 years later, ruling out the possibility of tobacco being present during the reign of Ramses circa 1213 BC.

Some years later, Dr. Svelta Balabanova, a forensic toxologist at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at ULM, followed up on Dr. Lescott’s findings with yet more intriguing evidence. In order to eliminate the possibility of contemporary contamination Dr. Balabanova obtained samples of intestinal tissue from deep inside Ramses, rather than the external layers of skin and cloth, and much to her amazement she discovered traces of cannabis, coca and tobacco, laid down in his body cells ‘like rings on a tree’.

For her fellow researchers this still was not enough proof despite her excellent reputation, as such evidence contradicted conventional explanations of intercontinental contact thousands of years in the past. But, a decade later in 1992, seven ancient Egyptian mummies were flown from the Cairo Museum to Munich for further analysis.

Dr. Balabanova conducted a series of gas chromatography tests on samples of the seven mummies, one of which was the mummified remains of Henut Taui, 'the lady of the two lands', a priestess who lived sometime during the reign of the 21st Dynasty of ancient Egypt around 1000 B.C. Each individual revealed the presence of nicotine and cocaine, and both the mummies and the results were deemed entirely credible.

‘It may be therefore implied that Egypt obtained these plants in trade with far flung urbanity from all over the ancient world’, wrote author/researcher Dr. Alexander Sumach. ‘Prepare to warm up to the plausible notion of intercontinental cultural contact that was either sustained, or else in play to some extent during every phase of human history.’ [1]

Professor Martin Bernal, a historian at Cornell University is one of many scholars who conceded that ancient trade links which vastly predate present calculations must have existed; ‘We’re getting more and more evidence of world trade at an earlier stage.’ Besides, he is not alone in his hypothesis, more details of transoceanic contact can be found in my latest book.

History tells us that on September 20, 1519, Ferdinand Magellan set out from the coast of Spain with his expedition, intent on being the first man in recorded history to successfully circumnavigate the world by sea. Despite many sources claiming that he succeeded in this immense task, the truth of this tale states that having become embroiled in a local war, Magellan was killed during battle on April 27, 1521.

According to historic accounts, it was his personal slave Enrique of Malacca (above) who ultimately succeeded where his master had failed, and managed to navigate the vast ocean the entire way around.

History speaks of many ancient crossings of both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the past but evidence has come to light which extends the timeline of these activities thousands of years beyond the presently accepted figures.

Pitcairn Island, an isolated volcanic formation which lies 1,350 miles south-east of Tahiti in the Pacific Ocean, was first officially sighted in 1767. The population of Pitcairn today is made up of descendants from survivors of the 215-ton Royal Navy transport ship the HMS Bounty, which was the victim of a dramatic mutiny in 1789 by Master’s Mate Fletcher Christian, who ultimately led his fellow mutineers to the island before disembarking then burning the famous ship. Here they established what they must have believed to have been the first colony in such a remote spot.

But they were not the first.

In 1820, a rock inscription written in the Libyan dialect of ancient Egyptian was reportedly discovered on Pitcairn Island that read:

Our crew, wrecked in a storm, made land thank God. We are people from the Manu region. We worship Ra in accordance with the scripture. We behold the sun and give voice.

Manu is a highland area of Libya. So, the question remains how did such distant travellers reach these shores in ancient Egyptian times and why has this particular piece of evidence been ignored ever since? Is it because officially, no sailors ever crossed the Pacific that far back in history?

John L. Sorenson and Carl L. Johannessen studied evidence from archaeology, historical and linguistic sources, ancient art, and conventional botanical studies, which revealed ‘conclusive evidence that nearly one hundred species of plants, a majority of them cultivars, were present in both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres prior to Columbus’ first voyage to the Americas.’ [2]

Their research paper ‘Scientific Evidence for Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Voyages’ explains that many plant species, over half of which consisted of flora of American origin that spread to Eurasia or Oceania, can only have been distributed to foreign shores via transoceanic voyages led by ancient mariners.

‘This distribution could not have been due merely to natural transfer mechanisms, nor can it be explained by early human migrations to the New World via the Bering Strait route,’ state the authors.

Sorenson and Johannessen claim that, ‘The only plausible explanation for these findings is that a considerable number of transoceanic voyages in both directions across both major oceans were completed between the 7th millennium BC and the European age of discovery.’[3]

Such controversial scientific findings contradict accepted notions of the plausible dates associated with transoceanic travel, but as the authors insist, ‘Our growing knowledge of early maritime technology and its accomplishments gives us confidence that vessels and nautical skills capable of these long-distance travels were developed by the times indicated.’

The presence of anomalous maps only serves to reinforce the notion that trans-oceanic travel took place thousands of years earlier than is currently accepted. We shall take a close look at these maps in another post.

This article is an extract from The Myth Of Man by J.P. Robinson.

For full references please use source link below