The dragon in ancient China

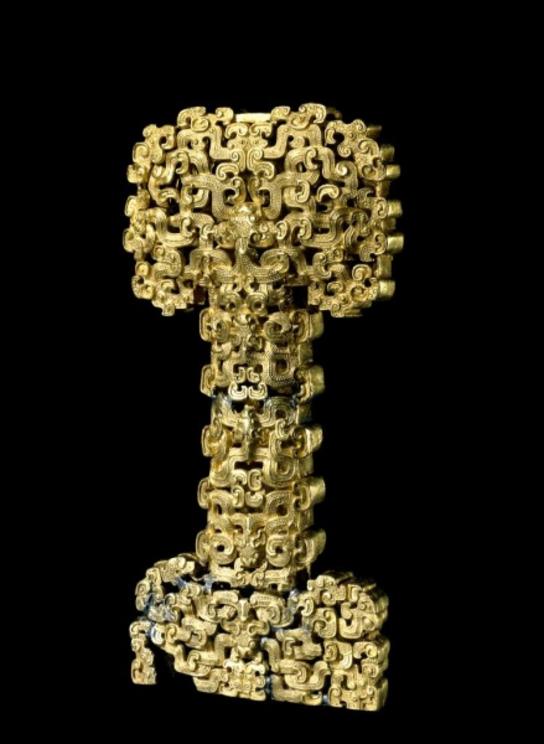

Dragons appear in the mythology of many ancient cultures but nowhere else in the world was the creature quite so revered as in China. There, in marked contrast to other world mythologies, the dragon was almost always seen in a positive light and particularly associated with life-giving rains and water sources. Considered the most auspicious year sign, worn on the robes of emperors, depicted in the most precious materials from gold jewellery to jade figurines, and with countless references in literature and the performing arts, the dragon was everywhere in ancient China and looms as large today in the Chinese psyche as ever.

Origins & Physical Attributes

One of the earliest creatures to appear in the tales and legends of ancient China, the dragon is most often depicted as a giant and lithe beast which dwells in either water sources or clouds. The Chinese dragon is extraordinarily powerful, and when it flies, it is usually accompanied by lightning and thunder. When, by whom, and on what reality the dragon was first invented is not known, although some historians suggest a link with rainbows and a 'serpent of the sky' which is seen after rain showers or at waterfalls. Carved jade dragons have been excavated at sites of the Hongshan culture, which can be dated to 4500-3000 BCE, far before any written records of the creature appeared. The historian R. Dawson gives the following description of the Chinese dragon’s physical attributes:

As chief among the animals the dragon was supposed to be composed of outstanding features of other animals. The traditional description gives it the horns of a stag, the forehead of a camel, the eyes of a demon, the neck of a snake, the belly of a sea-monster, the scales of a carp, the claws of an eagle, the pads of a tiger, and the ears of an ox. (231)

Alternative descriptions give similar attributes but sometimes with the body of a snake, the eyes of a rabbit, the belly of a frog, and the antlers of a deer. Other qualities of the dragon were that it could change its shape and size at will and disappear or reappear wherever it wished.

The Chinese scholar Wen Yiduo suggested that this fantastic collection of beastly parts was actually based on the political union of several different tribes, each with a different animal as their totem. The dragon was, therefore, a symbolic representation of the assimilation of these tribes into a single nation. An interesting hypothesis, it does not, however, explain the appearance of dragons long before any such political associations existed in early Chinese communities.

Powers & Associations

Despite the dragon’s fearsome aspect it was not usually seen as the bad-intentioned monster that inhabits the myths of other cultures around the world where it is typically slain by a brave hero figure. Indeed, in China, the dragon was and is regarded as being a just and benevolent creature. It is for this reason they became associated with rulership and especially the emperors of China who, in their capacity as the holders of the Mandate of Heaven and as God's representative on earth, must always rule in a just and impartial manner for the good of all their subjects.

The Chinese populace, in general, considered the dragon as a lucky symbol & bringer of wealth.

Another reason rulers should emulate dragons is that the creature was considered one of the four most intelligent animals (along with the phoenix, unicorn, and tortoise). One famous myth tells of a dragon actively helping a ruler, Yu the Great (c. 2070 BCE), the legendary founder of the Xia dynasty, who was helped by a dragon (or actually was a dragon) and a turtle to manage the floodwaters which were devastating his kingdom and so control them into a better irrigation system.

The populace, in general, considered the dragon as a lucky symbol and bringer of wealth. Further, ancient farmers thought dragons brought much-needed rains and water to aid their crops. Dragons were also thought responsible for strong winds, hailstorms, thunder, lightning, and tornadoes - the latter are still known today as 'dragon’s whirlwind' or long juan feng. It is also interesting to note that many early depictions of dragons in jade are circular.

In rural communities, there was a dragon dance to induce the creature’s generosity in dispensing rain and a procession where a large figure of a dragon made from paper or cloth spread over a wooden frame was carried. Alternatively, small dragons were made of pottery or banners were carried with a depiction of a dragon and written prayers asking for rain. Attendants would follow the procession carrying buckets of water and, using willow branches, they would splash onlookers and cry “Here comes the rain!”. When it seemed that a drought was imminent, another appeal for rain was to draw pictures of dragons which were hung outside the home.

The dancing processions had another handy purpose too, which was to ward off illnesses and disease, especially in times of epidemics. The dragon dance became a part of rural festivals and came to be closely associated with the Chinese New Year celebrations. The link between dragons and rain, dancing and healing may all derive from shamanism, commonly practised in ancient China.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.