The conquistadors encounters with giants

After a failed invasion of Northern Florida the Spanish conqueror and explorer Pánfilo de Nárvaez retreated back to port with a ragged bunch of restless men. More than half of his platoon had either been killed by the savage Florida jungles or were picked off by killer native attacks. Supplies had vanished, and when Narváez returned to the harbor he discovered that his ships had all disappeared. Returning to Cuba without him. He ordered the construction of four large rafts and told his fellow soldiers that this is “where New Spain ends”. It is not known for certain where and when Narváez died.

The last man to see Narváez alive and tell of it was Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, a junior officer of the Narváez expedition. According to Cabeza de Vaca, when he asked Narváez for more food and provisions Narváez refused, basically saying “every man for himself.” The rafts took off for Cuba but were destroyed in a hurricane. Around thirty men survived the sinking of the rafts, but Narváez was not among them. Cabeza de Vaca and the remaining Spanish survivors washed ashore near modern-day Tampa Bay. They quickly formed an expedition to reach a Spanish settlement in Mexico and regroup there, thinking it was only a few miles away, but after a series of battles with hostile natives they ended up rafting their way into southwestern Texas. Traveling west along the Colorado River, de Vaca and the survivors of the ill-fated expedition became the first Europeans to see a bison, or American buffalo. De Vaca returned to Spain nine years later and published his story. It was the bestseller of its time. In it there are references to Conquistador encounters with giants.

De Vaca’s astounding tales mention an encounter with giant natives during a raid while in Florida: When we attempted to cross the large lake, we came under heavy attack from many giant Indians concealed behind trees. Some of our men were wounded in this conflict for which the good armor they wore did not avail. The Indians we had so far seen are all archers. They go naked, are large of body, and appear at a distance like giants. They are of admirable proportions, very spare and of great activity and strength. The bows they use are as thick as the arm, of eleven or twelve palms in length, which they discharge at two hundred paces with so great precision that they miss nothing.

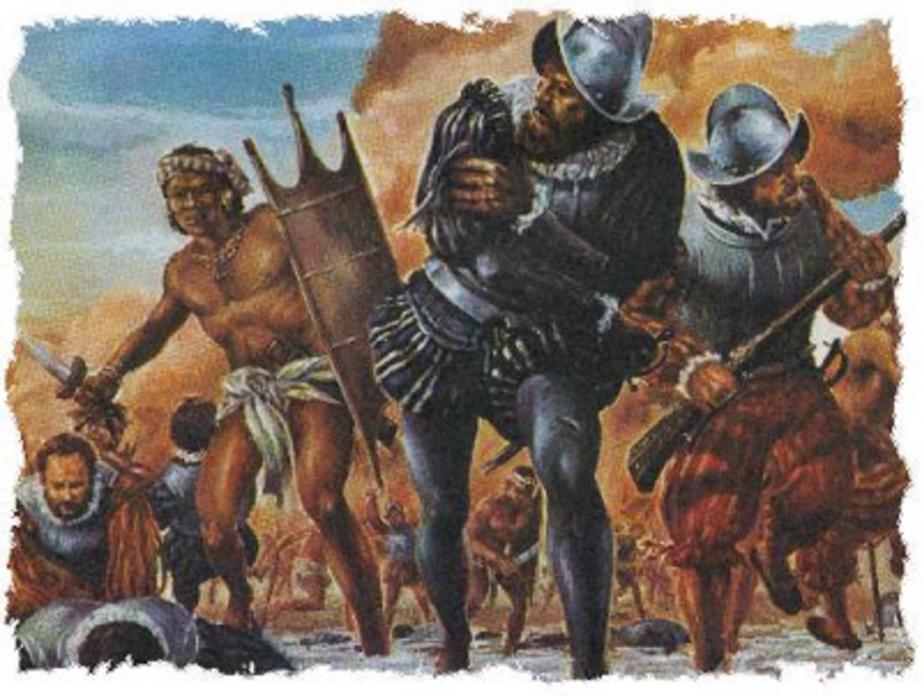

In 1539 Hernando De Soto followed in Nárvaez’s footsteps sailing nine ships into Tampa Bay. As they ventured inland, they encountered various tribes each with a giant that reigned as chief. For protection the Conquistadors took these chiefs hostage and called them guests. When the natives realized becoming guests meant being turned into slaves, the local tribes, led by Chief Copafi of the Apalachee, sparked an uprising. After weeks of warfare the chief was finally captured in a battle near what would become Tallahassee. Copafi was described as a man of monstrous proportions. Hernando De Soto’s encounters with giants continued as he pushed further inland in 1539. Traveling with more than six hundred men and two hundred horses, he trekked through North Florida, the southern swamps of Georgia, and the landlocked crossroads of western Alabama. Before dying of fever near the western banks of the Mississippi.

Rodrigo Ranjel, De Soto’s private secretary, wrote a diary detailing the expedition. The new lands they explored were ruled by the giant Native American chief Tuscaloosa and upon the Conquistador's arrival, the Chief's son fiercely approached De Soto's calvary. Ranjel writes: Seeing him we paused, dumb with amazement. For, though but a youth...he towered on high. A great-limbed giant: heads of tallest men reached only to his breast. After a three day march De Soto and fifteen soldiers entered Tuscaloosa's village, and discovered that the chief was a giant ten times mightier than his son and turned out to be the tallest and most handsomely shaped Indian they saw during all their travels. After a few days of watching colorful war dances, Tuscaloosa was persuaded to join De Soto on their quest towards Mobile. While on the trail two of De Soto's soldiers turned up missing and the returning scouts returned to warn De Soto about the many Native Americans that had gathered for rebellion. De Soto, brave and defiant, approached the town and its high walls. A welcoming committee of painted warriors, clad in robes of skins and headpieces with vibrantly colored feathers, came out to greet them. A group of young Native American maidens followed, dancing and singing to music played on crude instruments. De Soto entered the town with his most trusted soldiers, Tuscaloosa, and the chief ’s entourage. The Spaniards stood in a piazza, surrounded by a stream of foreign colors and fluttering sounds. From here De Soto saw some eighty houses within the village. Several of them were described as large enough to hold at least one thousand people. Unknown to De Soto, more than two thousand Native American warriors stood in concealment behind the walls. After some of the chiefs from the town joined him, Tuscaloosa withdrew into the village, warning De Soto with a severe look to leave at once. Under a hail of arrows, De Soto and most of his men retreated from the village. After regrouping and devising their strategy, the Spaniards gained entry to the village, killed the chief's giant son, set fire to the buildings, and massacred the city’s inhabitants.

Despite the death of his son and overall carnage left in the wake, Tuscaloosa escaped. Riding deep into unknown lands, De Soto and his men marched to capture him, but the giant chief disappeared, and the pursuing Spaniards found only abandoned cities with massive mounds.

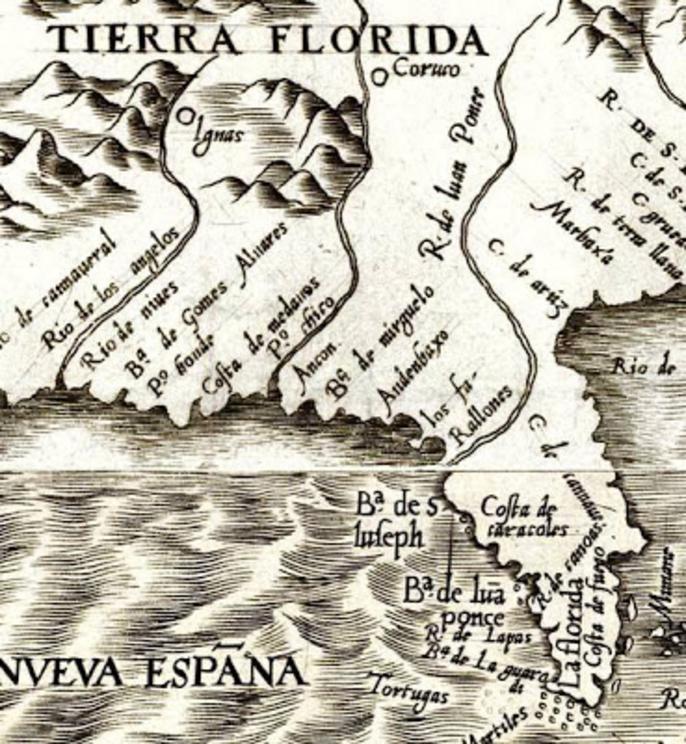

In 1519, Alonzo Álvarez de Pineda mapped the lands along the Gulf Coast, strategically marking the various rivers and bays, noticeable landmarks, and porting areas, all of which belonged to the king of Spain. After covering the coastlines from Florida to as far as Tampico, Mexico, Pineda sailed back to the mouth of the Mississippi River. Pineda was the first Spanish explorer to venture up the mighty Mississippi, and he reports finding a large settlement of native villages inhabited by giants. After the giants proved to be friendly, Pineda and crew settled among them to rest and make repairs. Pineda detailed the abundance of gold found in the river, and how the natives wore plenty of gold-engraved ornaments. It’s amazing how Pineda was more interested in the lands, good food, and the shock of discovering giants than he was in gold. He also noted that other than giants the tribes also had a race of tiny pygmies as well. Pineda described the tribe that settled near the Mississippi river as: A race of giants, from ten to eleven palms in height. As he sailed back to his home base in Jamaica, he made note of more giants, like the famed gargantuan's of the Karankawas encountered on the various islands of the Texas coast. When Pineda returned, he presented Francisco de Garay, the Spanish governor of Jamaica, with the first maps and sketches of the entire Gulf Coast. These maps also included Pineda’s writings about the fantastic race of giants living there. These sketches and writings are known as Garay’s Cédula and were archived by the famous Spanish compiler Martín Fernández de Navarrete. They can be found today by visiting the Archivo General de Indias, in Seville, Spain.

Twenty years after Pineda mapped the Gulf, Francisco Coronado

marched with a huge expedition across the American Southwest searching for the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola, or what we refer to today as El Dorado. While on their quest Coronado’s expedition crossed paths with several tribes of Indian giants. We have this information thanks to the writings of Pedro de Castaneda, who accompanied Coronado and wrote the complete and amazing history of the expedition. A fascinating tale concerning giants found in Castaneda’s book details the journey made by Hernando de Alarcón. Low on provisions, a frantic Coronado sent Alarcón to find a river that could bring supplies more easily to the Spanish outposts along the California and Mexican coasts. After nearly destroying his ships and missing the waiting party at the rendezvous point, Alarcón haphazardly floated up the mouth of the murky Colorado River. Alarcón and his men became the first Europeans to fight the rough rapids as he brought his fleet into the heart of the Colorado River, reaching as far as the lower reaches of the Grand Canyon. While coasting up the river, Alarcón and his men came upon a settlement of an estimated two hundred giant warriors. These giants, amazed by foreign intruders on the riverbanks, were ready to attack. But Alarcón defused the situation by making peace and offering gifts, which eventually won them over. These giants were later categorized with the prevailing tribes of the area as being the Cocopa Indians. A thousand more members of this giant tribe were discovered and reported farther upstream.

Discoveries of giants have also been reported in Mexico. The Dominican friar Diego Durán is responsible for writing some of the earliest Western books on the history and culture of the Aztecs. His family moved from Spain to Mexico City when he was very young, which allowed him to grow up around the remaining natives of Mexico. While attending school he was frequently exposed to Aztec culture, then under the colonial rule of Spain. He continued to study and travel within the remaining city-states of the Aztec empire. In Texcoco he learned to speak and read the native Nahuatl Aztec language. By winning the Aztecs’ trust, he was able to gain access to a vast amount of knowledge concerning the history of pre-Columbian Mexico. His writings are some of the oldest known surviving texts that give us actual firsthand narratives from the ancient Aztecs. Because he spent thirty-two years among the Aztecs gathering information, learning how to read ancient native hieroglyphics, and interviewing old shamans, scholars regard Durán’s work as extremely important. In The History of the Indies of New Spain, he exhaustively describes the history of Mexico from its mysterious ancient origins up to conquest and occupation by the Spaniards. In these writings the Aztecs were not shy when it came to talking about giants. But Durán didn’t need to hear or read about them, he could see them. While living in Mexico he came in contact with giant Indians on several occasions. Writing about these encounters, he says emphatically: It cannot be denied that there have been giants in this country. I can affirm this as an eyewitness, for I have met men of monstrous stature here. I believe that there are many in Mexico who will remember, as I do, a giant Indian who appeared in a procession of the feast of Corpus Christi. He appeared dressed in yellow silk and a halberd at his shoulder and a helmet on his head. And he was all of three feet taller than the others.

During his thirty-two years among the Aztecs, Duran also interviewed many old Indians knowledgeable in the ancient ways and traditions of their people. From all these sources he learned about the giants. Bernardino de Sahagun and Joseph de Acosta, two other notable historians of about the same period, also knew about a tribe of giants who once occupied central Mexico, but Duran's book offers us the best and most complete account. Duran writes that, according to the Aztecs, the giants and a bestial people of average size once had this land all to themselves. Then, in A.D. 902, six tribes of people from Teocolhuacan, which "is found toward the north and near the region of La Florida," began arriving in Mexico. They soon took possession of the country. These six kindred tribes included the Xochimilca, the Chalca, the Tecpanec, the Colhua, the Tlalhuica, and the Tlaxcalans. A seventh tribe, the Aztecs, were brothers to these people, but they "came to live here three hundred and one years after the arrival of the others." When these six tribes had settled, Duran continues, "they recorded in their painted books the type of land and kind of people they found here. These books show two types of people, one from the west of the snow-covered mountains toward Mexico, and the other on the east, where Puebla and Cholula are found. Those from the first region were Chichimecs and the people from Puebla and Cholula were 'The Giants,' the Quiname, which means 'men of great stature.' "The few Chichimecs on the side of Mexico were brutal, savage men, and they were called Chichimecs because they were hunters. They lived among the peaks and in the harshest places of the mountain where they led a bestial existence. They had no human organization but hunted food like the beasts of the same mountain, and went stark naked without any covering on their private parts....When the new nations came, these savage people showed no resistance or anger, but rather awe. They fled towards the hills, hiding themselves there.... The newly arrived people seeing, then, that the land was left unoccupied, chose at will the best places to live in. The other people who were found in Tlaxcala and Cholula and Huexotzinco are said to have been 'Giants.' These were enraged at the coming of the invaders and tried to defend their land. I do not have a very true account of this, and therefore will not attempt to tell the story that the natives told me even though it was long and worth hearing, of the battles that the Cholultecs fought with the Giants until they killed them or drove them from the country. "These Giants lived no less bestially than the Chichimecs, as they had abominable customs and ate raw meat from the hunt. In certain places of that region enormous bones of the Giants have been found, which I myself have seen dug up at the foot of cliffs many times. These Giants flung themselves from precipices while fleeing from the Cholultecs and were killed. The Cholultecs had been extremely cruel to the Giants, harassing them, pursuing them from hill to hill, from valley to valley, until they were destroyed. "Even if we detain the reader a little, I should like to tell the manner in which the people of Cholula and Tlaxcala annihilated that evil nation. This was done by treason and deceit. They pretended to want peace with the Giants, and after having assured them of their good will they invited them to a great banquet. An ambush was then prepared. Some men slyly robbed the guests of their shields, clubs, and swords. The Cholultecs then appeared and attacked. The Giants tried to defend themselves, and, as they could not find their weapons, it is said that they tore branches from the trees with the same ease as one cuts a turnip, and in this way defended themselves valiantly. But finally all were killed."

In his History of the Indies, Joseph de Acosta tells a story of the giants very similar to Duran's, but he also adds this eyewitness account: When I was in Mexico, in the year of our Lord one thousand five hundred eighty six, they found one of those giants buried in one of our farms, which we call Jesus del Monte, of whom they brought a tooth to be seen, which (without augmenting) was as big as the fist of a man; and, according to this, all the rest was proportionable, which I saw and admired at his deformed greatness...We must not holde this of the giants to be strange or a fable, for at this day, we find dead mens bones of an incredible bigness.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo marched as a swordsman in the army under Hernán Cortés during the conquest of Mexico. After surviving these expeditions he lived to be an old man and wrote what is regarded as an exceptionally accurate narrative of the famous campaign. His book would come to be known as The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. Unfortunately Díaz died before seeing his book published. Fifty years later the manuscript was found in a Madrid library and finally published in 1632. The book provides an eyewitness account of the conquest of Mexico, and it remains one of the most significant sources documenting the collapse of the Aztec Empire and the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Díaz recounts the history of the now-defeated Tlaxcatec Indians, mentioning a race of enormous giants that had once inhabited their land. During these encounters Díaz even had the chance to examine firsthand evidence of this long-forgotten race. He writes: They said their ancestors had told them that very tall men and women with huge bones had once dwelt among them. But because they were a very bad people with wicked customs they had fought against them and killed them, and those of them who remained had died off. And to show us how big these giants had been they brought us the leg-bone of one, which was very thick and the height of an ordinary-sized man, and that was a leg-bone from the hip to the knee. I measured myself against it, and it was as tall as I am, though I am of a reasonable height. They brought other pieces of bone of the same kind, but they were all rotten and eaten away by the soil. We were all astonished by the sight of these bones and felt certain there must have been giants in that land.

An Italian scholar from Venice, Antonio Pigafetta, traveled with famous Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his crew on their voyage to the Indies. During the expedition Pigafetta became Magellan’s assistant and kept an accurate journal that detailed the various encounters with native giants. In Magellan’s Voyage: A Narrative of the First Circumnavigation, there are numerous references to giants. Pigafetta amusingly writes: We had been two whole months in this harbor without sighting anyone when one day (without anyone expecting it) we saw on the shore a huge giant, who was naked, and who danced, leaped and sang, all the while throwing sand and dust on his head. Our Captain ordered one of the crew to walk towards him, telling this man also to dance, leap and sing as a sign of friendship. This he did, and led the giant to a place by the shore where the Captain was waiting. And when the giant saw us, he marveled and was afraid, and pointed to the sky, believing we came from heaven. He was so tall that even the largest of us came only to midway between his waist and his shoulder.

Throughout Pigafetta's narrative the giant indians repeatedly point to and ask if the Conquistadors had come from the sky. This is a very interesting side note that ties well into the ancient astronaut theory. Why the hell would they ask if they were from the skies if they had never seen anyone from the sky? Pigafetta was among the surviving 18 men who returned to Spain in 1522. The other 240 men of the expedition all died, including Magellan.