Rongorongo hieroglyphs written with shark teeth from Easter Island remain indecipherable

Two dozen wooden objects bearing rongorongo inscriptions, some heavily weathered, burned, or otherwise damaged, were collected in the late 19th century and are now scattered in museums and private collections. None remain on Easter Island.

The objects are mostly tablets shaped from irregular pieces of wood, sometimes driftwood, but include a chieftain’s staff, a bird-man statuette, and two reimiro ornaments. There are also a few petroglyphs which may include short rongorongo inscriptions. Oral history suggests that only a small elite was literate and that the tablets were sacred.

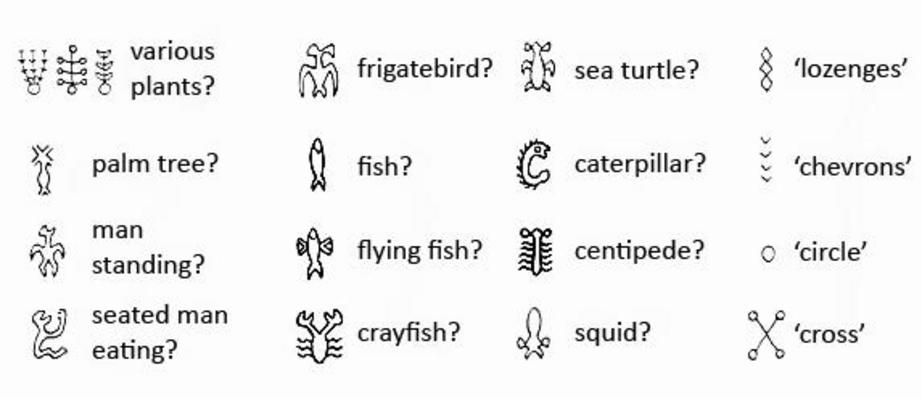

Rongorongo is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Easter Island that appears to be writing or proto-writing. Numerous attempts at decipherment have been made, none successfully. Although some calendrical and what might prove to be genealogical information has been identified, not even these glyphs can actually be read. If rongorongo does prove to be writing and proves to be an independent invention, it would be one of very few independent inventions of writing in human history.

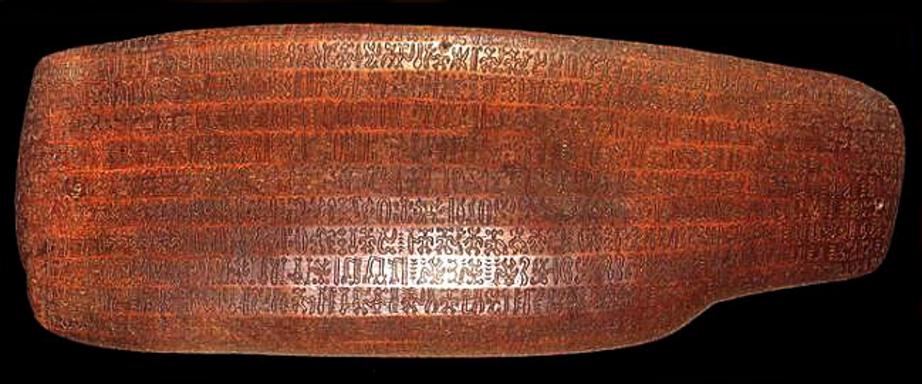

Verso of rongorongo Tablet B, ArukuKurenga.Source: Wikipedia/Public Domain

Authentic rongorongo texts are written in alternating directions, a system called reverse boustrophedon. In a third of the tablets, the lines of text are inscribed in shallow fluting carved into the wood. The glyphs themselves are outlines of human, animal, plant, artifact and geometric forms. Many of the human and animal figures, have characteristic protuberances on each side of the head, possibly representing eyes.

Individual texts are conventionally known by a single uppercase letter and a name, such as Tablet C, the Mamari Tablet. The somewhat variable names may be descriptive or indicate where the object is kept, as in the Oar, the Snuffbox, the Small Santiago Tablet, and the Santiago Staff.

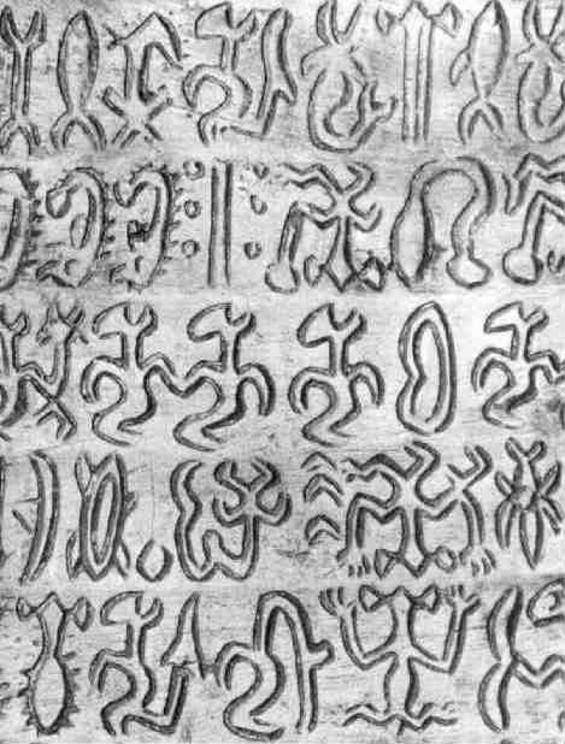

A closeup of the verso of the Small Santiago Tablet, showing parts of lines 3 (bottom) to 7 (top). The glyphs of lines 3, 5, and 7 are right-side up, while those of lines 4 and 6 are up-side down. Source Wikipedia/Public Domain

According to oral tradition, scribes used obsidian flakes or small shark teeth, presumably the hafted tools still used to carve wood in Polynesia, to flute and polish the tablets and then to incise the glyphs.(See shark tooth tools.) The glyphs are most commonly composed of deep smooth cuts, though superficial hair-line cuts are also found. In the closeup image at right, a glyph is composed of two parts connected by a hair-line cut; this is a typical convention for this shape. Several researchers, including Barthel, believe that these superficial cuts were made by obsidian, and that the texts were carved in a two-stage process, first sketched with obsidian and then deepened and finished with a worn shark tooth. The remaining hair-line cuts were then either errors, design conventions (as at right), or decorative embellishments. Vertical strings of chevrons or lozenges, for example, are typically connected with hair-line cuts, as can be seen repeatedly in the closeup of one end of tablet B below. However, Barthel was told that the last literate Rapanui king, Nga‘ara, sketched out the glyphs in soot applied with a fish bone and then engraved them with a shark tooth.

British archaeologist and anthropologist Katherine Routledge undertook a 1914–1915 scientific expedition to Rapa Nui with her husband to catalog the art, customs, and writing of the island. She was able to interview two elderly informants, Kapiera and a leper named Tomenika, who allegedly had some knowledge of rongorongo. The sessions were not very fruitful, as the two often contradicted each other. From them Routledge concluded that rongorongo was an idiosyncratic mnemonic device that did not directly represent language, in other words, proto-writing, and that the meanings of the glyphs were reformulated by each scribe, so that the kohau rongorongo could not be read by someone not trained in that specific text. The texts themselves she believed to be litanies for priest-scribes, kept apart in special houses and strictly tapu, that recorded the island’s history and mythology. By the time of later ethnographic accounts, such as Métraux (1940), much of what Routledge recorded in her notes had been forgotten, and the oral history showed a strong external influence from popular published accounts.