Pity for Petronilla de Meath: Ireland’s first witch burning

There is a famous Jonathan Swift quote about how the law impacts upon the rich and poor in unequal measure which reads, “Laws are like cobwebs, which may catch small flies, but let wasps and hornets break through.”

This interpretation was certainly the case three centuries earlier when Irish law decreed that Petronilla de Meath was to become the first woman to be burnt to death following accusations of witchcraft on November 3, 1324. Because witchcraft was not yet listed on the statute books in Ireland the term used to convict Petronilla was actually ‘Heresy’.

Heresy as Opposed to Witchcraft

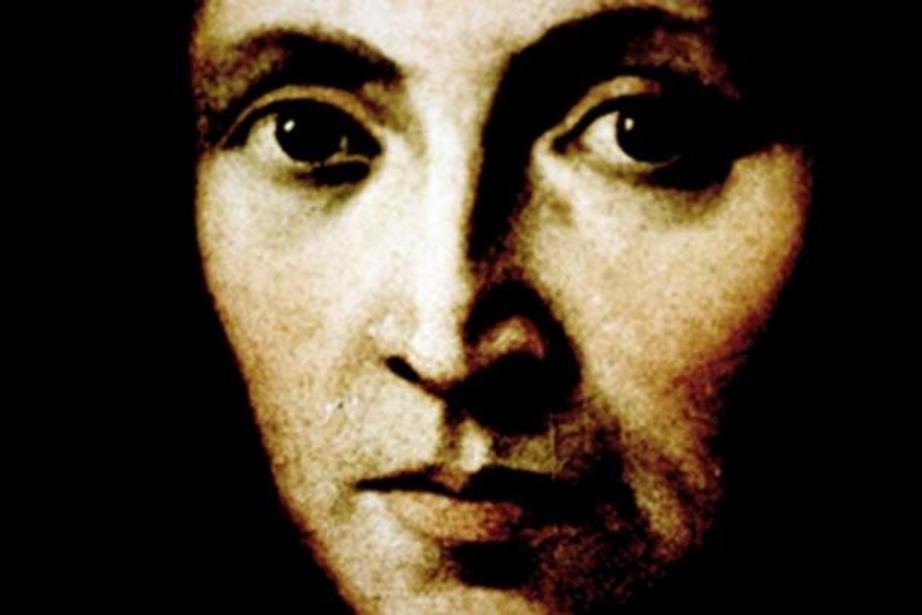

Petronilla de Meath, a maidservant, was 24 years old when she was accused and convicted of being an accomplice of her employer, Dame Alice Kyteler, who was the real and intended target of the accusations. Alice Kyteler was a powerful noblewoman who had outlived three husbands and was onto her fourth marriage when her various stepchildren came together to bring accusations of sorcery, murder, and witchcraft. The probable reason for this was just how powerful and rich Alice Kyteler had become at her step-children’s expense and some of them felt that she had cheated them out of their rightful financial legacies. But because Kyteler was, by this time, so well connected and influential in her own right, she was able to flee Ireland and escape the charges. Unfortunately, this left her workers and servants, including Petronilla de Meath, to face the fury and wrath of the accusers and the Bishop of Ossory, Richard de Ledrede.

The powerful and rich Alice Kyteler left her children and servants to face the fury and wrath of the accusers. (Public Domain)

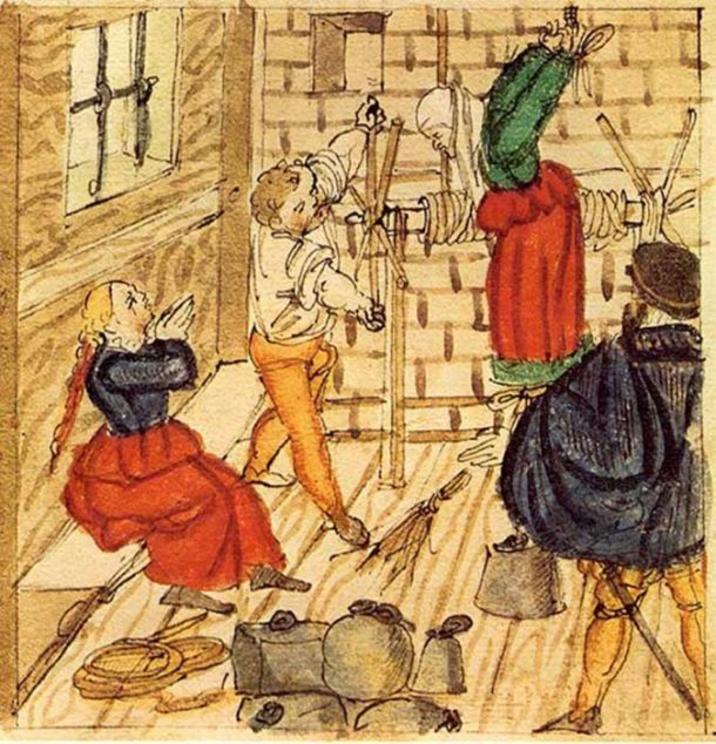

During her incarceration, Petronilla was tortured and flogged and brought through six different parishes to be humiliated and persecuted before she eventually confessed to the charges brought against her. Considering the punishment and pain being inflicted upon her it is surprising that Petronilla even lasted as long as she did before conceding to the accusations.

Demons and Flying Ointments

Many of these charges were typical of the time and were concocted based upon church superstition and a willful attempt to suppress and distort ancient folkloric practices and cures. These accusations included the sacrificing of animals and burying their remains at crossroads so as to conjure demons. Petronilla was also charged with making potions from the body parts of children and participating in lustful associations with an entity who appeared as dark-skinned man and who could transform into a cat.

In 1233, Pope Gregory IX had issued the Papal Inquisition against heresy which clergymen and church leaders were using to suppress ancient and indigenous European pagan beliefs and practices.

Edicts of Gregory IX. (Public Domain)

Included in this decree was a description of a black cat which Pope Gregory claimed would appear to witches and heretics. This demon would then supposedly transform into a shining man with cat’s legs that the sect’s members would proceed to kiss on the hindquarters before a group orgy would ensue. Catholic teachings would then be banished from the minds of these neophytes and witches as they pledged loyalty to heretical deities. Pope Gregory’s edict also describes the ingestion of toad emissions to replace the Eucharist and it is interesting that included in the charges against Petronilla is the claim that she concocted potions to influence and kill.

A witch and her toad and cat familiars. (Public Domain)

Toad emissions were also associated with flying ointments and another of Petronilla’s later confessions was that she and Alice Kyteler would rub a ‘magical’ potion on a wooden stick which would then enable them to fly.

Irish Folkloric Associations

Aside from the typical symbolism of the witches’ familiar included in the charges, there are also specific Irish folkloric associations which remind of a fairy being called a Púka, or Pooka. This was an Irish spirit or elemental often thought to be able to change shape and they are usually associated with ancient places and pagan sites.

A Pooka/Puck Marionette. (Duesseldorfer Marionetten-Theater/CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are many variants of the etymology of Púka which link it to similar fairy spirits in Scottish, French and North European lore. Another version is the English Hobgoblin, ‘Puck’ or Robin Goodfellow. One explanation for this is that the word itself comes from the Old Norse term ‘Pook’ which is most often translated to mean ‘nature spirit’.

Puck, 1789. (Public Domain)

Some descriptions of the Púka speak of a black horse or cat, whereas others describe a demon or fairy exhibiting both human and animal physiology, so today we can appreciate how people at the time might have also noticed this archetypal succession.

As is often the case with myths and legends, tough, many descriptions exist with slightly different cultural translations. Depending on where you live, a Púka might be helpful or mischievous, good or bad, or, most likely a mix of many trickster-type characteristics. For Petronilla and her fellow accused this was just a further proof of their guilt, unfortunately, and a tangible way to influence not only the well-off gentry but the rural poorer population who would have been well aware of Ireland’s spirit lexicon.

The Burning

It is beyond imagining what Petronilla must have gone through during her long and torturous incarceration and we can only wonder how she lasted through such a period of suffering, agony, and distress.

So-accused ‘witches’ were punished with shocking brutality. (Christian Kadluba/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Finally, Petronilla’s short life was brought to a grizzly end when she was burned at the stake before a huge gathering of onlookers in Kilkenny on November 3, 1324.

It has been suggested that Petronilla’s son, Basil, was also accused of witchcraft but, somehow, Alice Kyteler managed to have him smuggled away and save his life. Whether this is true or not is hard to say as it has never been proven one way or another.

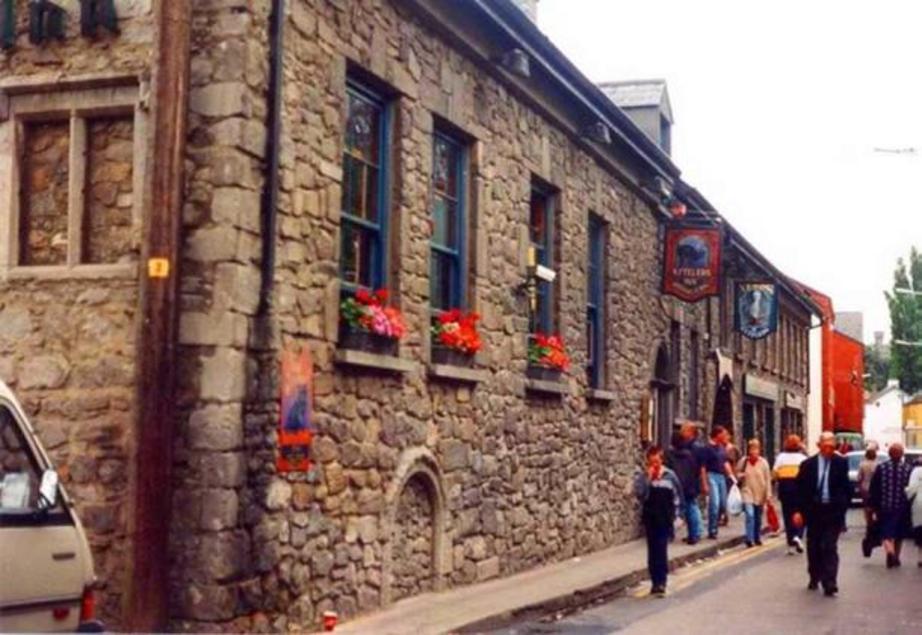

Today, the inn where Petronilla worked for Alice Kyteler is still standing and has become a tourist attraction in its own right. Some guests have claimed to see the ghost of a lady on the premises and although this apparition is often cited to be Lady Kyteler herself, one must wonder whether Petronilla de Meath has more reason to impress her life-story upon the patrons visiting the location of her accusations and the town of her eventual demise.

Kyteler's Inn, Kilkenny City, Ireland, in 1998. (Elisa.Rolle/CC BY-SA 4.0)

A Forgotten Legacy?

During Ireland’s civil war many buildings were destroyed which included libraries of historical and legal documentation relating to trials and criminal charges. To this end it is impossible to say how many women were ultimately accused and convicted of witchcraft and heresy in Ireland. Based upon popular academic opinion the number is deemed to be quite small compared to other European countries, but we really have no way of knowing for sure.

While the sensationalism of witch burning is something that might sear itself onto the consciousness of a town or village, it was often the case that many of those accused of witchcraft were punished by other means. Women were banished from their homes and sent out into an unforgiving landscape where they would die a slower and less visible death. Another punishment for women accused of witchcraft was hanging or strangulation before burning. For men the punishment was most often being drawn and quartered but, again, with the destruction of past documentation we really have no estimates of how many people were killed in this way.

Torture used against accused witches, 1577. (Public Domain)

What we do know is that many of those accused of witchcraft were also associated with fairies and spirits of the land. Perhaps this also created an environment of both respect and wariness within rural populations and, of course, many of these ‘wise-women’, the Bean Feasa as they were known, were often the same women a family would turn to in times of childbirth, sickness, and for remedies and cures pertaining to love, healing and curses.

Ireland’s recorded figures relating to witch burnings may be incomplete, but in the case of Petronilla de Meath we at least have the chance to remember the terrible injustices that strong and independent women had to face because of intolerance and superstition.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.