Origin of mysterious 2,700-year-old gold treasure revealed

New analysis unveils the origin of the storied Carambolo Treasure, and despite previous claims, it has nothing to do with Atlantis.

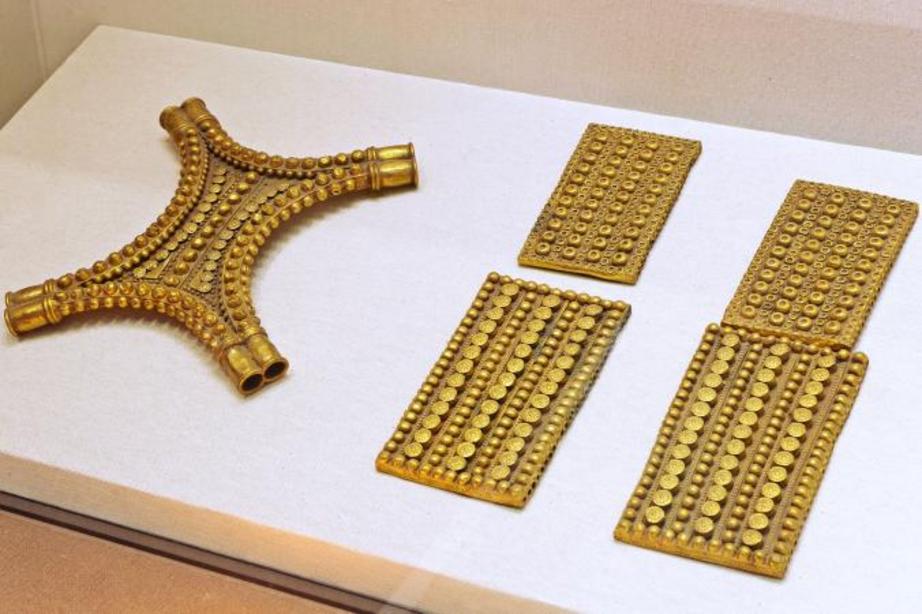

The Carambolo Treasure consists of 21 pieces of gold jewelry discovered by construction workers near Seville, Spain in 1958. Photograph by Karsten Moran, The New York Times, Redux

New chemical analysis has solved the mystery regarding the origin of the Carambolo Treasure, a magnificent hoard of ancient gold objects discovered by Spanish construction workers near Seville in 1958.

When the 2,700-year-old treasure was first found, it instantly sparked speculation and debate about Tartessos, a civilization that thrived in southern Spain between the ninth and sixth centuries B.C. Ancient sources described the Tartessians as a wealthy, advanced culture, ruled by a king. That wealth, and the fact that the Tartessians seemingly 'disappear' from history about 2,500 years ago, has led to theories equating Tartessos with the mythical site of Atlantis.

Another side of the debate held that the jewelry came with the Phoenicians – a Semitic, seafaring culture from the Near East which first arrived in the western Mediterranean in the eighth century B.C. and established a trading port at what is now modern-day Cádiz.

“Some people think that the Carambolo Treasure comes from the East, from the Phoenicians,” says Ana Navarro, the director of the Archaeological Museum of Seville and one of the authors of a recent study of the treasure published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. “With this work, we know that the gold was taken from mines in Spain.”

Locally sourced

The Carambolo Treasure is a collection of 21 pieces of goldwork, including a necklace with intricately carved pendants, several chest decorations shaped like ox skins, and lavish bracelets. While archaeologists believe the horde was deliberately buried in the sixth century B.C., most of the jewelry was likely made two centuries earlier. Navarro says nothing quite like it has been discovered from this period in Spain in terms of sheer extravagance.

The treasure includes gold plaques in the shape of rectangles and ox hides, and weighs more than five pounds. Photograph by Jose Lucas, Alamy

To settle the debate on the origins of the Carambolo Treasure, Navarro and her research team used chemical and isotopic analysis to examine tiny gold fragments that had broken off from one of the pieces of jewelry. The analysis revealed that the material likely came from the same mines associated with monumental underground tombs at Valencina de la Concepcion, which date to the third millennium B.C. and are also located near Seville. The authors of the paper assert that the jewelry of the Carambolo Treasure marks the end of a continuous gold-processing tradition that began some 2,000 years earlier with Valencina de la Concepcion.

Multicultural heritage

Navarro says that while the gold was sourced locally, the jewelry was mostly manufactured using Phoenician techniques. A Phoenician temple has been identified in the area where the Carambolo Treasure horde was found, and the treasure itself is likely the product of a mixed culture of Near-Eastern Phoenicians and local Tartessians.

Alicia Perea, an archaeologist with the Spanish National Research Council’s Centre for Human and Social Sciences who specializes in gold technology and has studied the Carambolo Treasure, agrees that Tartessos was likely a mixed culture of native Western Mediterranean peoples and Near Eastern seafarers.

“A Phoenician boy marries a local girl—this is, to put it, very simple,” she explains.

Perea commends the new study in general terms, especially as isotopic and chemical analyses of gold objects are relatively rare in Spain. But she takes issue with the attempt to draw a direct association between the culture surrounding the Carambolo artifacts and that surrounding the earlier Valencina discoveries.

“This line doesn’t exist. The only line that connects both worlds, may I say, is the material,” she says.

Some researchers believe that this necklace from the horde may have originated on the island of Cyprus, based on its design. Photograph by De Agostini, Getty Images

The conclusions of recent analysis are somewhat limited, however, as only fragments from one piece of the 21-item Carambolo treasure were examined. Perea has published a study on the technological processes used in the manufacture of the jewelry, and says that while some of the pieces were likely made locally based on style and technique, the necklace with the carved pendants may have originated from Cyprus based on its design.

While researchers continue to unravel the mysteries surrounding Tartessos, both Navarro and Perea are in complete agreement when it comes to the potential connection between the ancient civilization and the Atlantis theory.

“That’s complete madness. That has nothing to do with archaeology or scientific research,” Perea says.