New analysis challenges idea that humans caused Australia’s megafauna extinctions

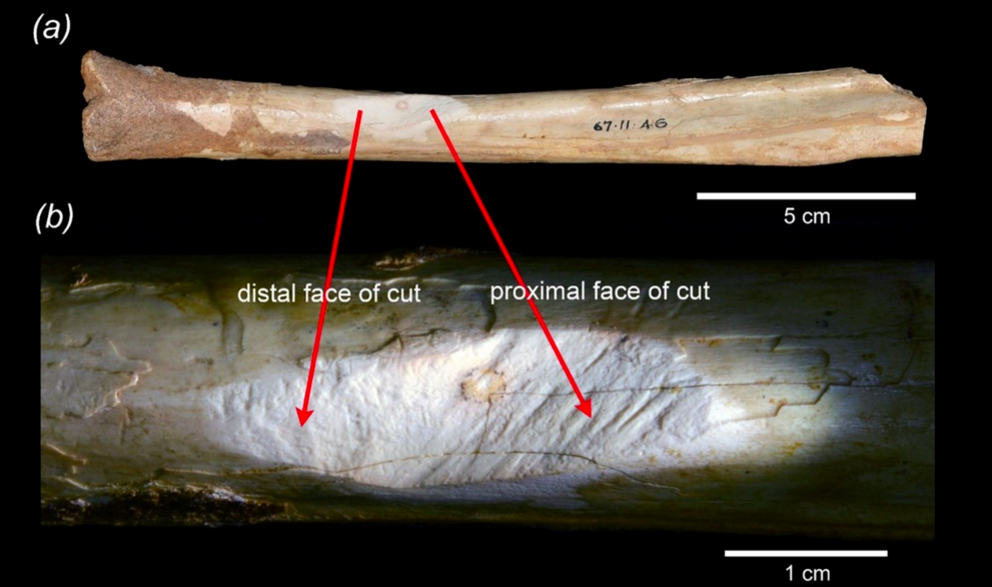

The fossilised lower leg bone (tibia) of an extinct, giant ‘sthenurine’ kangaroo was unearthed in the early 1900s alongside other bone fragments from the Mammoth Cave in southwestern Western Australia.

A study published in 1980 concluded that distinctive cut marks found on the bone were not created naturally. Instead, the researchers interpreted the marks as evidence the animal was butchered by people shortly after its death.

These findings have been considered the only “hard evidence” that some of Australia’s megafaunal species may have been hunted, scavenged or butchered by humans and that this may have contributed their extinctions.

Decades later, new analysis has now determined the original finding was wrong.

“As a scientist, it’s not just my job but my responsibility to update the record when new evidence comes to light,” says palaeontologist Michael Archer, a professor at the University of New South Wales who was involved in the original study and the new analysis.

“Back in 1980, we interpreted the cut as evidence of butchery because that was the best conclusion we could draw with the tools available at the time. Thanks to advances in technology, we can now see that our original interpretation was wrong.”

Archer and collaborators used a high-resolution 3D imaging technique called micro computed tomography (micro-CT) to re-examine the specimen. The technique uses X-rays to scan an object slice by slice and peer inside of it inside.

This revealed at least 9 deep cracks running along the length of the bone, 2 of which pass through the area which has been cut.

“All of these appear to be shrinkage cracks that developed long after the animal was dead,” writes Archer and his co-authors in the new study published in Royal Society Open Science.

“Importantly, there is also one short transverse crack within the area of the cut that extends between 2 of the longitudinal cracks.”

Because this crack ends where it meets the 2 length ways cracks, the authors conclude it must have developed after they did.

“Further, because it occurs within the laminar bone matrix of the shaft within the area of the cut, it seems probable that this transverse crack resulted from the same forces that were involved in producing the incision itself.

“Consequently, the date of the incision must have post-dated dehydration of the shaft, i.e. the incision did not occur when the bone was still fresh, in contrast to the conclusion reached by Archer et al. [in 1980].”

The new findings suggest the cut, which is still considered not to have been made by natural processes, occurred long after death of the kangaroo and probably after fossilisation.

“For decades, the Mammoth Cave bone was a ‘smoking gun’ for the idea that Australia’s First Peoples hunted megafauna, but with that evidence now overturned, the debate about what caused the extinction of these giant animals is wide open again, and the role of humans is less clear than ever,” says Archer.

“Hard evidence is required before it can be concluded that predation on the now extinct megafaunal species by First Peoples contributed to their extinction, particularly given the long history First Nations peoples have had in valuing and sustainably utilising wildlife in Australia.

“If humans really were responsible for unsustainably hunting Australia’s megafauna, we’d expect to find a lot more evidence of hunting or butchering in the fossil record. Instead, all we ever had as hard evidence was this one bone – and now we have strong evidence that the cut wasn’t made while the animal was alive.”