Mass extinctions can occur without warning

The most severe mass extinction in Earth's history occurred with almost no early warning signs, according to a new study.

The end-Permian mass extinction, which took place 251.9 million years ago, killed off more than 96 per cent of the planet's marine species.

It also wiped out 70 per cent of its terrestrial life – a global annihilation that marked the end of the Permian Period.

Now experts have found that in the approximately 30,000 years leading up to the mass extinction, there is no geologic evidence of species starting to die out.

The researchers also found no signs of any big swings in ocean temperature or dramatic fluxes of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The most severe mass extinction in Earth's history occurred with almost no early warning signs, say scientists. The Great Dying was a hugely catastrophic event triggered by a massive volcanic eruption that ran for almost one million years in what is today Siberia (stock image)

HOW WAS THE FINDING MADE?

Most attention has been devoted to well-preserved layers of fossil-rich rocks in the Meishan section in China,

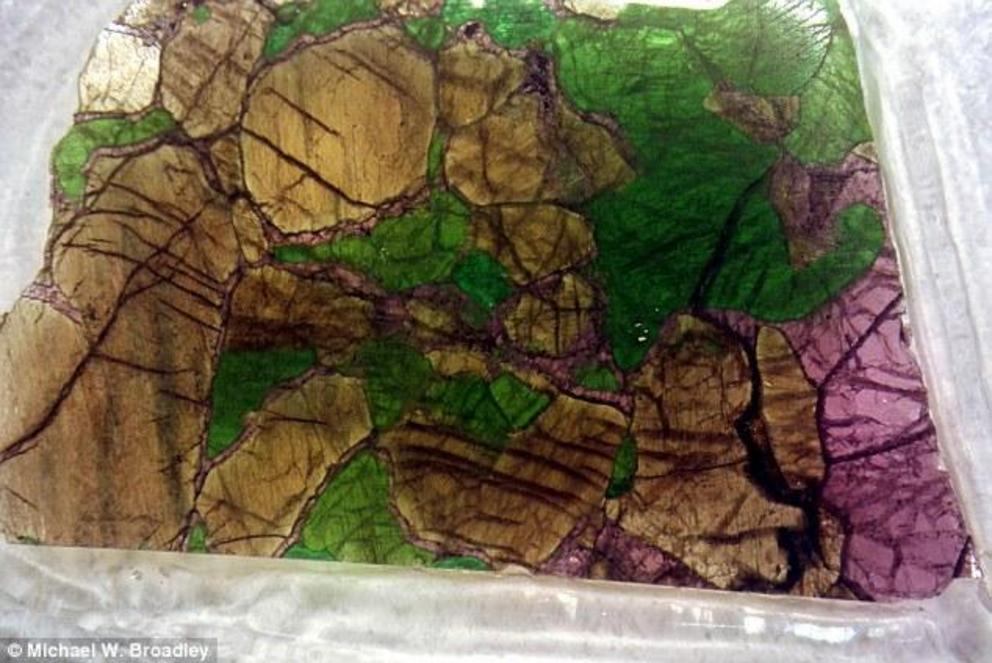

In 1994 experts went looking for a more complete extinction record in Penglaitan. This image shows the Permian-Triassic boundary interval at Penglaitan.

Researchers have now studied samples from ash beds that were deposited by volcanic activity that occurred as nearby seafloor was crushed slowly under continental crust.

From their analysis, they were able to determine that the end-Permian extinction occurred suddenly, around 252 million years ago, give or take 31,000 years.

Researchers at MIT, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and elsewhere found that when ocean and land species did die out, they did so en masse, over a period that was geologically instantaneous.

For over two decades, scientists have tried to pin down the timing and duration of the end-Permian mass extinction to gain insights into its possible causes.

Most attention has been devoted to well-preserved layers of fossil-rich rocks in eastern China, in a place known to geologists as the Meishan section.

Scientists have determined this section of sedimentary rocks was deposited in an ancient ocean basin, just before and slightly after the end-Permian extinction.

As such, the Meishan section is thought to preserve signs of how Earth’s life and climate fared leading up to the calamitous event.

'We can say for sure that there were no initial pulses of extinction coming in,' says study co-author Jahandar Ramezani, a research scientist in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences.

'A vibrant marine ecosystem was continuing until the very end of Permian, and then bang — life disappears.

'And the big outcome of this paper is that we don't see early warning signals of the extinction. Everything happened geologically very fast.'

Most attention has been devoted to well-preserved layers of fossil-rich rocks in the Meishan section in China, but in 1994 experts went looking for a more complete extinction record in Penglaitan. This image shows the Permian-Triassic boundary interval at Penglaitan

The whole extinction interval at Meishan comprises just 12 inches (30 cm) of ancient sedimentary layers.

It’s likely that there were periods in this particular ocean setting when sediments did not settle, creating 'depositional gaps' during which any evidence of life or environmental conditions may not have been recorded.

In 1994, experts went looking for a more complete extinction record in Penglaitan, a much less-studied section of rock in southern China’s Guangxi province.

The Penglaitan section is what geologists consider 'highly expanded.'

Compared with Meishan’s 12 inches (30 cm) of sediments, Penglaitan’s sedimentary layers make up a much more expanded 89 feet (27 metres) that were deposited over the same period of time, just before the main extinction event occurred.

The researchers painstakingly collected and analysed samples from multiple layers of the Penglaitan section, including samples from ash beds that were deposited by volcanic activity that occurred as nearby seafloor was crushed slowly under continental crust.

Researchers painstakingly collected and analysed samples from ash beds that were deposited by volcanic activity that contain zircons – tiny mineral grains. This is a microscope image of zircon crystals separated for isotopic dating from the latest Permian ash bed at Penglaitan

A microscope slide photo showing a Permian fossil (center) surrounded by volcanic ash within the latest Permian layer immediately below the extinction horizon at Penglaitan. Foraminifers are single-celled marine organisms with characteristic multichambered shells

These ash beds contain zircons – tiny mineral grains that contain uranium and lead, the ratios of which researchers can measure to determine the age of the zircon, and the ash bed from which it came.

The team used this geochronology technique to determine with high precision the age of multiple ash bed layers throughout the Penglaitan section.

From their analysis, they were able to determine that the end-Permian extinction occurred suddenly, around 252 million years ago, give or take 31,000 years.

The full findings of the study were published today in the journal GSA Bulletin

In August, scientists announced they had unravelled the cause of the mass extinction, dubbed 'The Great Dying'.

It was triggered by a massive volcanic eruption that ran for almost one million years in what is today Siberia.

Until the finding, scientists were unsure of how the so-called Flood Basalts eruption was responsible for wiping out such a large proportion of life on Earth, since previous volcanic activity of this scale had not killed anywhere near as many species.

Some had suggested the eruption blanketed the Earth in a dense smog that blocked the sun's rays from reaching the planet's surface.

However, a new study revealed how chemicals released by the eruption released a huge reservoir of deadly chemicals into the air that stripped Earth of its ozone layer.

This eradicated the only protection Earth's inhabitants had against the sun's deadly UV rays, causing the death toll to skyrocket, compared to other major eruptions.

In a previous study, scientists analysed the chemical composition of mantle xenoliths (pictured), rock sections of the lithosphere - a section of the planet located between the crust and the mantle to find out more about the extinction event

Scientists at the Centre for Petrographic and Geochemical Research in Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy, France, studied rock from Earth's upper mantle to determine the cause.

They analysed the chemical composition of mantle xenoliths, rock sections of the lithosphere – a section of the planet located between the crust and the mantle – that gets captured by passing magma and erupted to the surface during eruptions.

Through analysis of the ancient samples, researchers attempted to determine the composition of the lithosphere.

They found that before the Flood Basalts took place, the Siberian lithosphere was heavily loaded with chlorine, bromine, and iodine.

These chemicals, all elements from the halogen group, seemed to disappear soon after the devastating volcanic eruption.

'We concluded that the large reservoir of halogens that was stored in the Siberian lithosphere was sent into the earth's atmosphere during the volcanic explosion,' said study lead author Michael Broadley.

'This effectively destroyed the ozone layer at the time and contributed to the mass extinction.'

Life on Earth looked very different during the Permian era.

The dominant land animals of the late Permian era were reptiles – precursors to the dinosaurs and crocodiles that would dominate the planet millions of years later.

Large herbivores, known as captorhinomorphs, which measured between sevent to ten feet (two and three-metres) in length, were common during this time, populating the land mass that is now North America and Europe.

Meanwhile, the fossil plant record for the Permian epoch consists predominantly of ferns, seed ferns, and mosses, which were adapted to survive in the marshes and swampy environments that covered a large proportion of the planet.

By the Late Permian period, scientists believe early protoangiosperms (precursors to flowering plants) started to emerge, showing a move towards drier areas.

The Permian seas came to be dominated by bony fishes with fan-shaped fins and thick, heavy scales. There were large reef communities that were home to squid-like nautiloids.

Ammonoids, which float in the water with their tightly coiled, spiral shells, are also widespread in the Permian fossil record.

All life on Earth today is descended from the roughly ten per cent of animals, plants and microbes that survived the mass extinction event.

Previously it was thought the eruption was so deadly because it blanketed the Earth in thick smog that blocked the sun's rays from reaching the planet's surface.

'The scale of this extinction was incredible,' said Mr Broadley at the time.

'Scientists have often wondered what made the Siberian Flood Basalts so much more deadly than other similar eruptions.'

WHAT WAS THE PERMIAN MASS EXTINCTION, KNOWN AS 'THE GREAT DYING'?

Around 248 million years ago, the Permian period ended and the Triassic period started on Earth.

Marking the boundary between these two geologic eras is the Permian mass extinction, nicknamed 'The Great Dying'.

This catastrophic event saw almost all life on Earth wiped out.

Scientists believe around 95 per cent of all marine life perished during the mass extinction, and less than a third of life on land survived the event.

In total, it is believed that 90 per cent of all life was wiped out.

All life on Earth today is descended from the roughly ten per cent of animals, plants and microbes that survived the Permian mass extinction.

Previously, it was believed a huge eruption blanketed the Earth in thick smog, blocking the sun's rays from reaching the planet's surface.

However, new findings suggest a massive volcanic eruption that ran for almost one million years released a huge reservoir of deadly chemicals into the atmosphere that stripped Earth of its ozone layer.

This eradicated the only protection Earth's inhabitants had against the sun's deadly UV rays.

This high-energy form of radiation can cause significant damage to living organisms, causing the death toll to skyrocket.