Decrypting the Temple of Edfu and the Edfu Texts

Temple of Edfu passage with glowing walls of Egyptian hieroglyphs on either side.

Edfu city is located between Luxor and Aswan in the southern area of Egypt. The city, which is situated on the west bank of the Nile, is world famous for its temple, which was built during the Ptolemaic period. The Temple of Edfu , dedicated to the god Horus, is the second largest temple in Egypt. After the Roman period, the temple was gradually buried by desert sand, and silt from the Nile. As a result, the temple was forgotten, and was only rediscovered during the 19 th century. Apart from its size and state of preservation, the Temple of Edfu is also notable for its large number of inscriptions, collectively known as the Edfu Texts, which seem to cover every available surface.

Temple of Edfu In the Old, Middle and New Kingdom Periods

The city of Edfu is known also by several other names. The ancient Egyptians, for instance, knew the city as Behdet, while the Greeks and Romans called it Apollonopolis. This latter name was a reference to the city’s chief god, Horus, whom the Greeks identified with their own god Apollo. Although Edfu is most famous for its Ptolemaic temple , the city’s history stretches much further back in time.

For instance, archaeological excavations in the western and northern parts of the town have uncovered material from the earlier periods of the town’s occupation. These include mastaba tombs from the Old Kingdom , and burials dating to the Middle Kingdom . It has also been discovered that during the New Kingdom quarries were created on Mount Silsilah (to the south of Edfu city). Sandstone was procured from these quarries and transported all over Egypt for construction works.

During the New Kingdom, a temple to Horus was built at Edfu. This temple was smaller than the current structure, and longer exists. The only element that remains of this New Kingdom temple is its pylon (a Greek term for the monumental gateway of an Egyptian temple), which is located to the east of the new temple, and faces the landing stage on the Nile. This is due to the fact that the Ptolemies built a new temple on the site of the older one.

The world-famous Temple of Edfu pylon or monumental gateway.

The world-famous Temple of Edfu pylon or monumental gateway.

The pharaoh who began the construction of the Temple of Edfu was Ptolemy III Euergetes, the third ruler of Ptolemaic Kingdom . During his reign, which lasted from 246 to 222/1 BC, Ptolemy managed to reunite Egypt and Cyrenaica, and triumphed over the Seleucids during the Third Syrian War. Egypt’s native temples benefitted greatly from Ptolemy III’s rule. Apart from initiating the building the Temple of Edfu, Ptolemy III also made donations to many other temples, and restored the divine statues plundered from the temples by the Persians. Incidentally, his epithet, ‘Euergetes’, means ‘Benefactor’.

Although the construction of the Temple of Edfu began in 237 BC, it was not completed by the time of Ptolemy III’s death. Nevertheless, the building of the temple continued. It was finally finished in 57 BC, during the reign of Ptolemy XII Auletes. The construction of the temple took such a long time to complete due to the many nationalistic uprisings in Upper Egypt during that period which disrupted the construction process.

The Ptolemies were not only facing internal problems, but external ones as well. By the time of Ptolemy XII, the fortunes of Ptolemaic Kingdom had waned, and it was no longer the mighty and prosperous state it once was. As a matter of fact, the Ptolemies were on the brink of losing their kingdom, as Egypt was absorbed by Rome in 30 BC, after the last Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra VII Philopator , was deposed by Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus).

Closeup of the god Horus statue in front of the pylon temple entranceway

Closeup of the god Horus statue in front of the pylon temple entranceway

Temple of Edfu: Main Architectural and Historical Features

Although the Ptolemaic dynasty was nearing its end, the Temple of Edfu, when it was completed, was a remarkable monument. As mentioned earlier, it is the second largest temple in Egypt. The largest temple, by the way, is the Temple of Karnak . Roughly speaking, the Temple of Edfu consists of a main entrance, a courtyard, and a chapel. The three parts of the temple are aligned along a main axis. Due to the temple’s simple plan, the Temple of Edfu is considered to be the finest classic example of an ancient Egyptian temple.

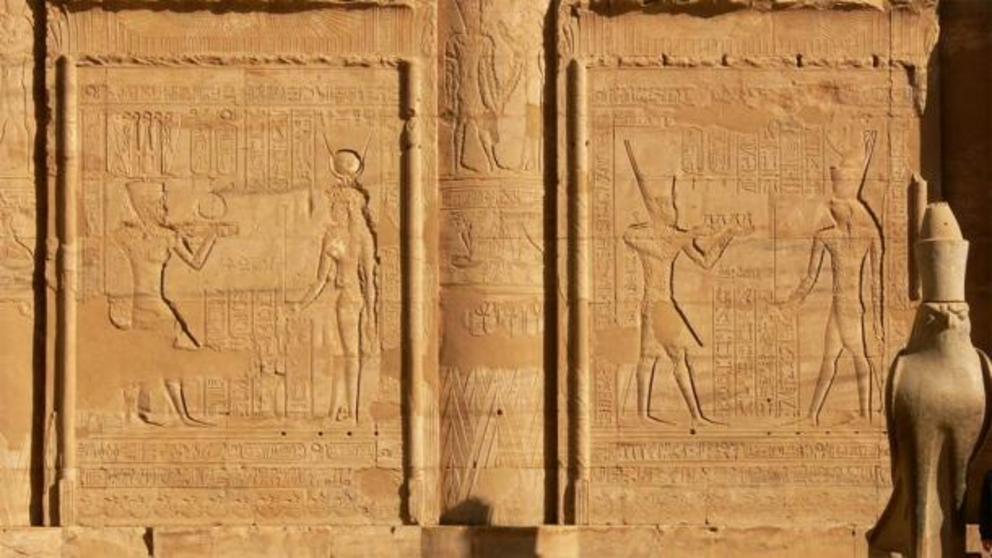

The Temple of Edfu’s pylon or monumental gateway faces south and is one of the most impressive features of the temple. The gateway rises to a height of 36 m (118 ft). Construction of the pylon gateway was initiated under the rule of Ptolemy IX Soter . The pylon is believed to have been completed later on, as the outstanding colossal reliefs on it depict Ptolemy XII. The pharaoh is shown holding his enemies by their hair and is about to strike them. This is the classic way to depict the pharaoh as the triumphant conqueror of Egypt’s enemies.

Closeup of the left side of Temple of Edfu pylon and its elaborate inscriptions

Closeup of the left side of Temple of Edfu pylon and its elaborate inscriptions

The temple gateway is also adorned with reliefs of Horus, who watches the pharaoh as he punishes his enemies. In addition, the pylon has four grooves on each side. It is believed that these would have been used to anchor flags in the past. Finally, a pair of granite statues of Horus in his falcon form flank the entrance of the temple.

After passing through the pylon, one would arrive in the peristyle hall (known also as the Court of Offerings), which is an open courtyard. Each of the three sides of the courtyard is surrounded by 32 columns. One of the most notable features of the peristyle hall is its festival relief, which is found on the inner walls of the pylon and continues along the bottom of the wall. One of the scenes in the relief depicts the Feast of the Beautiful Meeting, which was an annual fertility festival celebrating the reunion of Horus of Edfu and Hathor (his wife) of Dendera. Another pair of falcon statues can be found at the end of the peristyle hall. One of the them, however, lies on the ground, as it no longer has legs.

The peristyle hall is followed by the hypostyle hall, which is a roofed courtyard. This part of the temple is divided into two parts: the outer hypostyle hall and the inner hypostyle hall. The outer hypostyle hall was built during the reign of Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator, and two small chambers are found at its entrance. The one on the right was the temple library, where ritual texts were stored, while the one on the left was the hall of consecrations (known also as the robing room), where freshly laundered ritual robes and ritual vases were kept. The ceiling of the outer hypostyle hall is supported by 12 massive columns. Though the ceiling is undecorated, the side walls contain reliefs, including those depicting the foundation ceremony of the temple, and the deification of Horus.

The magnificent columns of the Temple of Edfu.

The magnificent columns of the Temple of Edfu.

The inner hypostyle hall is the oldest part of the Temple of Edfu and is known also as the Festival Hall. Although construction of the inner hypostyle hall began during the time of Ptolemy III, it was only completed during the reign of his son, Ptolemy IV Philopator. Like the outer hypostyle hall, this roofed courtyard also has 12 columns, though with a slightly different orientation. On the eastern side of the inner hypostyle hall is a chamber for storing liquid offerings, whereas solid offerings were kept in a chamber on the western side of the hall. In addition, there was a ‘laboratory’ where incense, perfumes, and unguents were prepared. The recipes for these sweet-smelling substances are inscribed on the walls of the ‘laboratory.’

Beyond the two hypostyle halls is the Hall of Offerings. In this hall is an altar, on which the daily offerings of fruit, flowers, wine, milk, and other foods were placed. During the Egyptian New Year Festival, the image of Horus would be carried to the temple’s rooftop via an ascending stairway attached to the hall. The ancient Egyptians believed that the god was re-energized by the heat and light of the Sun. After that, the image was returned to the Sanctuary via a separate descending stairway. The depiction of this ritual decorates the walls along the two stairways.

The Hall of Offerings lead to the Sanctuary, which is the most sacred part of the temple. Incidentally, the Sanctuary also contains the oldest object in the Temple of Edfu: the granite naos shrine of Nectanebo II, the last ruler of the Thirtieth Dynasty. Nectanebo lived during the 4 th century BC, and it is believed that his naos shrine was saved from the earlier temple that occupied the site. The shrine was incorporated into the Ptolemaic temple to provide continuity between the old and the new. This shrine would have contained a gold statue of Horus.

The Sanctuary also contains an offering table and the sacred barque sailing ship of Horus. During the New Year Festival, the statue of Horus would be placed on the barque and brought to the temple’s rooftop. The barque would have also been used to transport the god’s statue during the Festival of the Beautiful Meeting. Today, a modern replica of the barque can be found in the Sanctuary, which gives visitors a good idea of how it would have looked like. Reliefs in the Sanctuary depict Ptolemy IV worshipping Horus and Hathor. The Sanctuary is surrounded by a number of chapels and chambers dedicated to other gods, including Osiris, Ra, and Hathor. Lastly, a Nilometer, to the east of the Sanctuary, was used by temple priests to measure the level of the Nile.

Edfu Texts or Inscriptions: Copied, Studied and Translated

Despite the end of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Temple of Edfu continued to flourish during the Roman period. By the end of the 4 th century AD, however, the temple was abandoned, following the banning of paganism throughout the Roman Empire by the Emperor Theodosius . Over the centuries, desert sand and silt from the Nile covered the temple, eventually burying it entirely. It was only in 1860 that Auguste Mariette , a French Egyptologist, rediscovered the temple, and began to excavate it. As a consequence of its burial, the Temple of Edfu is one of the best-preserved temples in Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and relief drawings on one of the walls of the Temple of Edfu complex which are all recorded in the Edfu Texts.

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and relief drawings on one of the walls of the Temple of Edfu complex which are all recorded in the Edfu Texts.

Another impressive feature of the Temple of Edfu is its inscriptions, which cover the walls of the monument. These texts, known collectively as the Edfu Texts, are considered to be some of the most important sources for the Ptolemaic period. Considering that various Ptolemaic rulers were involved in the temple’s construction, the texts provide an insight into the political history and administration of the period. Apart from that, the Edfu Texts also contain religious ideas that were transmitted form earlier ages. This is an invaluable resource for modern scholars, as the texts have been used to help them understand older religious sources.

Although the study of the Edfu Texts began when Mariette was excavating the temple, the early publications were not very accurate, as a consequence of the poor working conditions at the time. The first reliable foundation for the study of the Edfu Texts was laid by another French Egyptologist, Émile Chassinet, who not only copied the inscriptions on the temple’s walls, but also its reliefs. It took Chassinet 40 years to complete this colossal task. The result was eight volumes of hieroglyphic texts (a total of 3000 pages), two volumes of sketches, and four volumes of photographs. The final major task was the translation of the inscriptions.

It is reported that that until the 1970s, only between 10% and 15% of the texts had been translated. In addition, the quality of these translations was not consistent. Therefore, in 1986, Dieter Kurth, a professor of Egyptology at the University of Hamburg initiated the Edfu Project. The Edfu Project is a “long-term project that is devoted to a complete translation of the Edfu inscriptions that meets the requirement of both linguistics and literary studies.”

Today, the Temple of Edfu is a popular tourist attraction. In addition, the government of Egypt, since 2003, has been seeking international recognition for the cultural and historical significance of the temple. Along with the Temple of Dendera , the Temple of Esna, and the Temple of Kom Ombo , the Temple of Edfu has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The four temples are grouped together as the ‘Pharaonic Temples in Upper Egypt from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.’