Crime in The Great Pyramid: the evidence mounts

Scott Creighton builds on evidence offered in The Great Pyramid Hoax, causing the conventional explanation for the origin of the Great Pyramid to seem all the more untenable.

In 1765 the British consul to Algiers, Nathaniel Davison, discovered a hidden chamber directly above the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid of Giza. He gained entry via a precarious climb using a rickety ladder at the south end of the pyramid’s Grand Gallery. It seems that the passage leading to this chamber had been accessible since the pyramid’s construction. The chamber’s dimensions were similar to those of the King’s Chamber directly below, although unlike the King’s Chamber, the compartment Davison discovered was very cramped, being only around three feet in height. As Davison explored, he found nothing but a floor several feet deep in bat dung—no hidden sarcophagus, no treasure and, as in the rest of the pyramid, not a single inscription. Little did Davison know that directly above the chamber which now bears his name, a further four chambers awaited discovery.

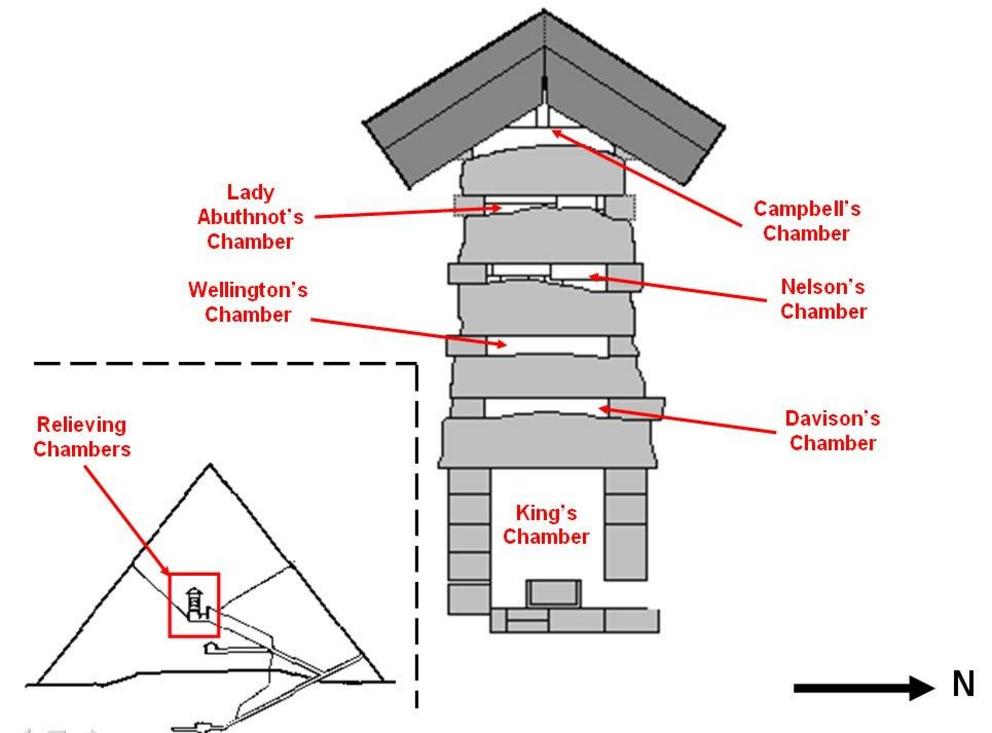

Seventy-two years after Davison’s discovery, British adventurer Colonel Richard William Howard Vyse, following the intuition of his colleague, Giovanni Caviglia, blasted his way into the four hidden compartments above Davison’s Chamber (Figure 1) using gunpowder. These four chambers, known today as the ‘Chambers of Construction’, were approximately the same size as Davison’s. However, in one very important way they were different; for upon the wall and roof blocks of these ‘Vyse Chambers’ were many painted inscriptions and, significantly, the name of the pyramid’s supposed builder, Khufu.

Figure 1: The ‘Chambers of Construction’ above the King’s Chamber.

The importance of these painted marks to Egyptology cannot be overstated. They are Egyptology’s ‘Holy Grail’, because they offer the only empirical evidence that directly connects Khufu to the Great Pyramid. As Egyptologist Dr Mark Lehner writes:

“Since nobody had entered from the time Khufu’s workmen sealed it until Vyse blasted his way in, the gang names clinch the attribution of this pyramid to the 4th-dynasty pharaoh, Khufu.”1

However, from the moment Colonel Vyse first presented these painted ‘quarry marks’ to the world, questions have surrounded them and suspicions have grown—particularly surrounding the king’s various names and whether they were fraudulently placed into the four chambers by Vyse and two of his closest assistants, Raven and Hill, or not.

Indeed, the more we analyse the painted inscriptions from the ‘Vyse Chambers’, the more errors and anomalies we find in them. Taken together, the evidence points towards the perpetration of an audacious hoax in the Great Pyramid by these men in 1837.

Let us now consider two pieces of this considerable body of evidence.

Odd Numbers

Early hieratic letters and numerals essentially consisted of cursively written or painted equivalents of the sculpted hieroglyphic signs.2 As such, their early orthography was not so far removed from their counterpart sculpted signs. However, as the millennia passed, the two forms diverged greatly from one another.3

One of the key differences between early hieratic script and their sculpted hieroglyphic equivalents is that hieratic script (like that allegedly discovered in the ‘Vyse Chambers’) was always and only written (and read) from right-to-left, whereas hieroglyphics are bi-directional.4 Both forms are also read from top-to-bottom.5

In 1837, hieratic script was barely understood by the Western world, and as the evidence reproduced in this article suggests, Vyse did not understand it either. Indeed, it seems that Vyse regarded the script in these chambers as painted hieroglyphic rather than hieratic quarry-marks, and that this misunderstanding caused Vyse to make a grave error in the placing of these hieratic numbers onto the roof blocks in Campbell’s Chamber.

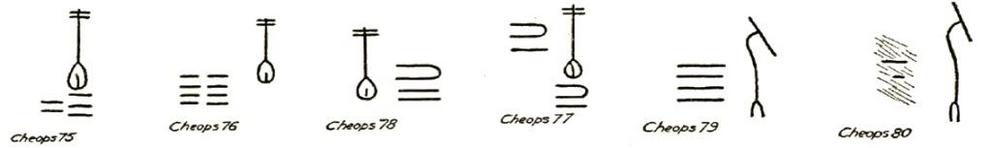

The painted marks in these chambers appear in a variety of orientations from their natural upright positioning. The conventional explanation for this apparent haphazard arrangement is that, originally, the marks would have been painted onto each block at the quarry in the natural upright manner.6 The builders of the chambers, unconcerned about the orientation of the painted marks on the blocks, would have then rotated each block (with it signs) to find the most efficient means of placing it within the various chamber walls.7 (Figure 2a-b).

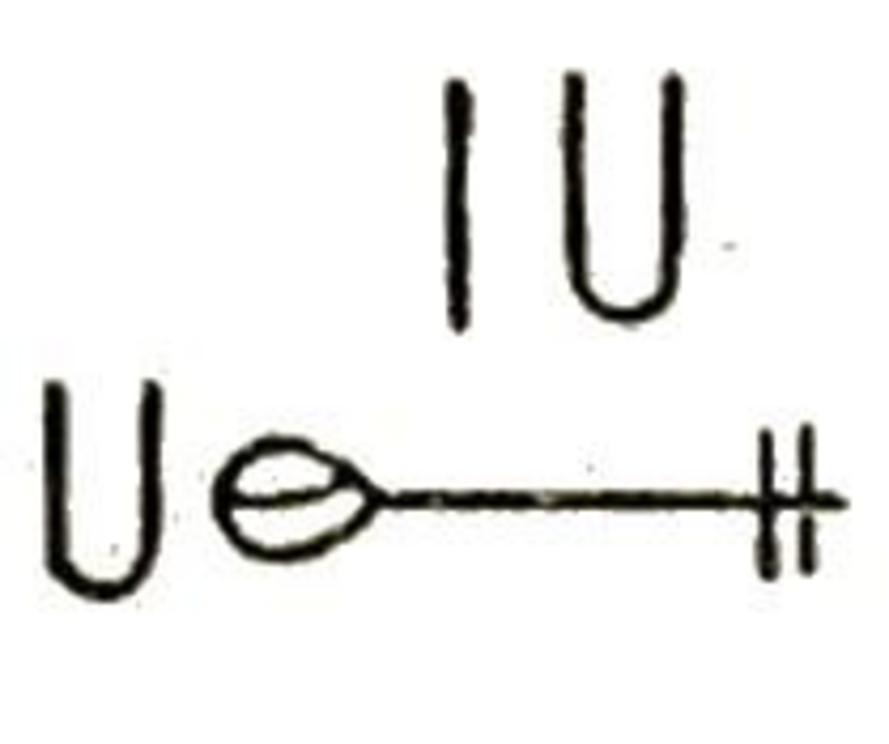

Figure 2a. “Hieratic” number sign (21) as it appears on the roof blocks of Campbell’s Chamber, in its actual (upside-down) yet incorrect orientation. (Image: John Perring 1837).

Figure 2b. “Hieratic” number sign (12) as it appears on the roof blocks of Campbell’s Chamber, in its actual (upside-down) yet incorrect orientation (Image based on Alan Rowe 1931).

The way that these signs appear on the roof blocks of Campbell’s Chamber is inconsistent with the grammatical rules of hieratic script. In hieratic script, a vertical stroke ‘|’ symbolizes 1 unit while a ‘∩’ sign symbolizes the value 10, thus ‘| | ∩’ = 12 and ‘| | | ∩ ∩’ = 23 and so on.8 Note also that in hieratic script the highest numerical value is always placed to the right of the lower values.9 This ensures that the higher value is always read first, i.e. from right-to-left. It is here that Vyse seems to have made a mistake.

If we rotate the painted numbers on these blocks to their natural upright position—so that they are presented as they would have “appeared at the quarry” (vis-à-vis the conventional explanation for their orientation)—then the lower unit strokes ‘| |’ end up on the right and the higher ∩ value on the left. This means that the signs cannot have been drawn on at the quarry and then rotated, unless drawn on incorrectly:

Figure 3. Rotating the signs so that they appear as they would have “at the quarry” (vis-à-vis the conventional explanation) suggests that this value on the roof block of Campbell’s Chamber has been incorrectly written with the higher value on the left instead of to the right.

Clearly, something here isn’t right. To offer an explanation consistent with the rules of Hieratic script, critics have proposed that these numbers were perhaps written sideways onto these blocks at the quarry (Figure 4), from top to bottom.10 Oriented in this way, the 90º rotated number signs will then have the higher unit values (∩) correctly placed above the lower unit values (| |) and are thus read first, top-down.

Figure 4: The hieratic sign for ‘12’ rotated 90º (sideways) so that the highest numerical value is read first (from top-to-bottom).

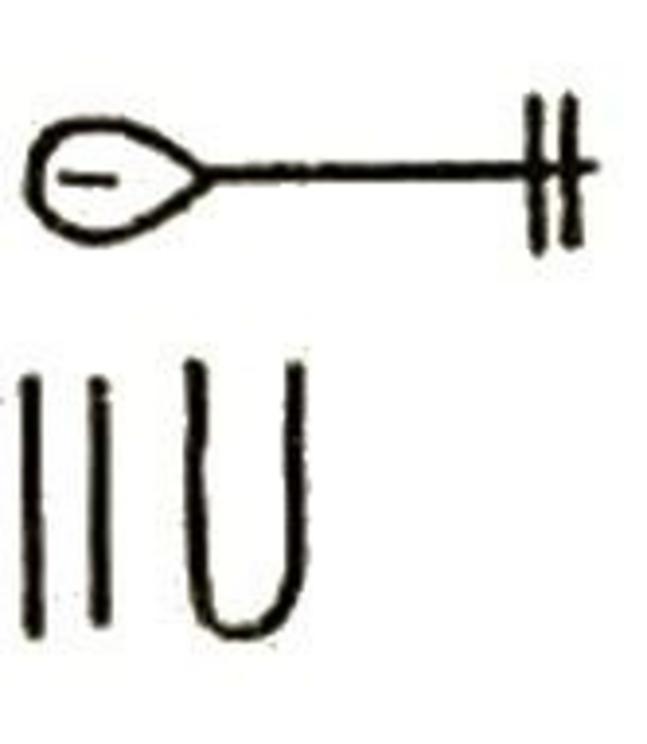

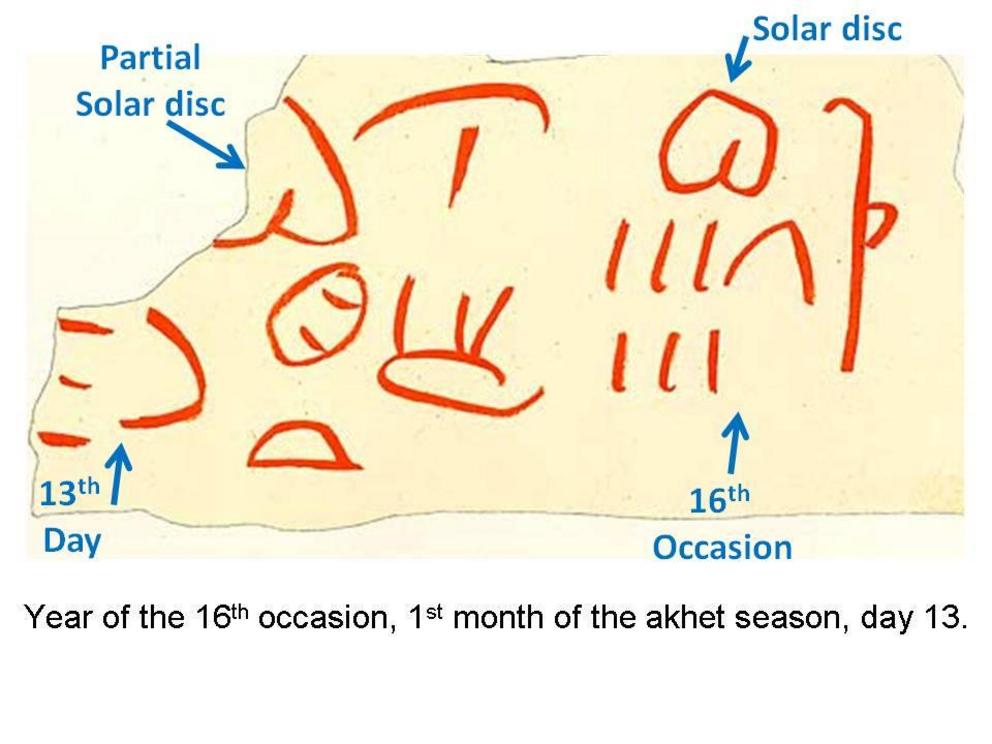

However, while the ancient Egyptians did indeed write certain hieratic numbers sideways in a style similar to that presented in Figure 4, this was only ever done when writing the calendar days of the month as observed in Figures 5a, 5b and 5c.

Figure 5a. Hieratic script showing regnal year 16 (with solar disc) and 1st month with upright numerals (and solar disc) but only with ‘day 13’ numerals rotated ninety degrees (sideways).11

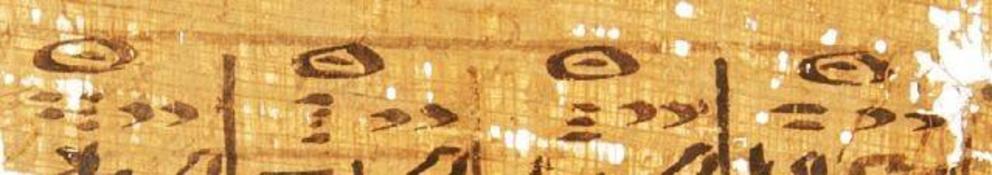

Figure 5b. The Wadi al-Jarf papyri with Hieratic script showing calendar day numerals 22-25 (with solar disc above), rotated ninety degrees (sideways).

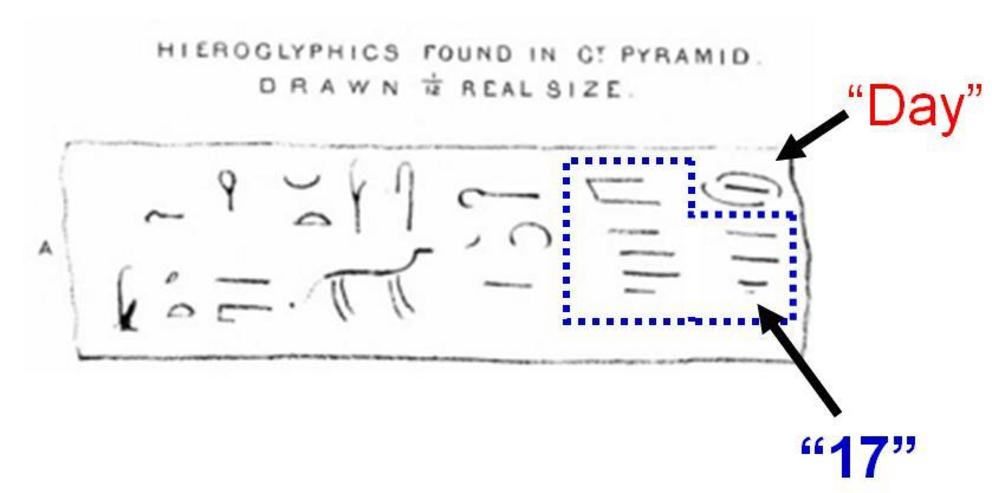

Figure 5c. Date signs in the pyramid of Neferirkare at Abusir. Again we see that the sideways number signs (in blue box) are accompanied with the hieratic solar disc sign (‘day’).12

This convention is confirmed by Egyptian language expert, Sir Alan Gardiner, who writes:

“In Hieratic the tens and units, when referring to the days of the month, are invariably laid on their side… Traces of a similar use, though as regards the units only, are sometimes found in Middle Kingdom hieroglyphic…” 13

Gardiner’s comment is consistent with the Old Hieratic palaeographic record. Here we find that the ancient Egyptians used unit and ten number signs rotated 90 degrees from their upright/vertical orientations to represent the days of the month.14 We also observe, as Gardiner states, that unit number values (1-9) were written sideways/horizontally in later periods. However, on no occasion in the Old Hieratic palaeographic record do we find a cardinal number ∩ rotated 90 degrees from upright that is not a date.15

Given the total absence of the solar disc sign from all of the number signs in Campbell’s Chamber (Figure 5d), it is highly unlikely that these signs represent calendar days, as some have suggested.16 As such, these signs should not be read sideways (from the top-down) but upright (from right-to-left). And since ancient Egyptian scribes were unlikely to write the cardinal number ∩ upright with the lower unit values placed on the right, then the number signs in this chamber are clearly anomalous.

Figure 5d. Hieratic numbers painted onto the roof blocks of Campbell’s Chamber. None of these numbers show any evidence of the solar disc sign that would indicate the numbers were to be read sideways, as dates.

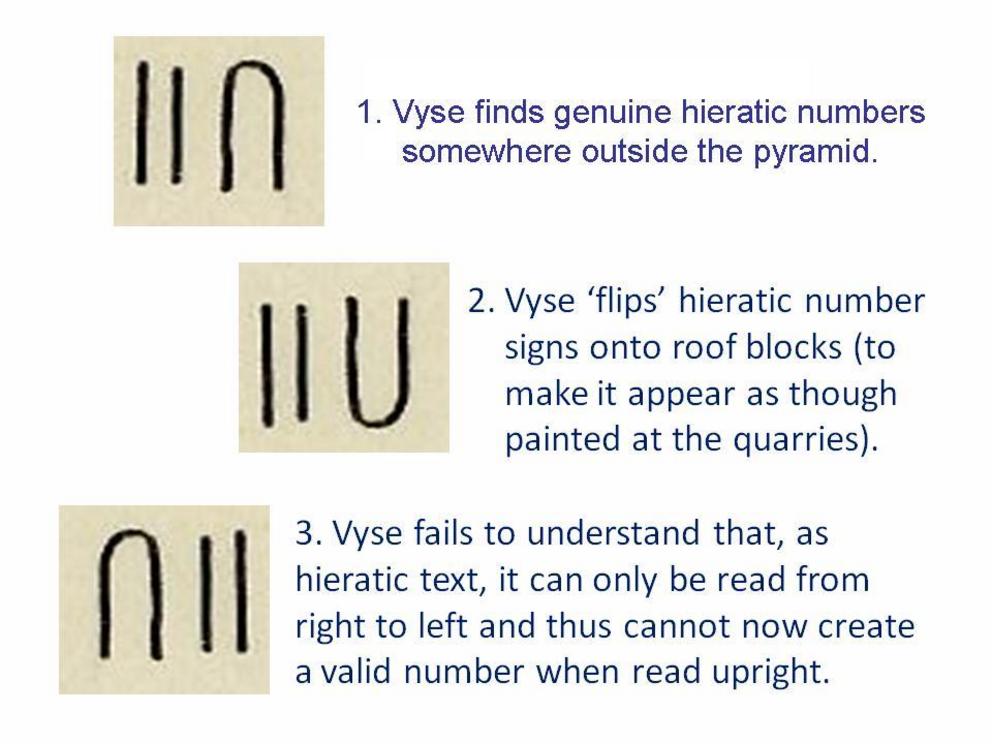

What we are therefore likely witnessing here is the work of someone who did not understand that ancient Egyptian hieratic script, unlike hieroglyphics, can only be read from right to left. That genuine hieratic numbers were simply flipped and painted onto these blocks to make them look as though painted onto the block at the quarry, is one simple way of explaining this anomaly (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The author’s explanation for the anomalous numbers in Campbell’s Chamber.

The Lost Symbol

Another piece of evidence that points to the committal of fraud in the Great Pyramid in 1837 concerns a small group of signs on a wall block in Lady Arbuthnot’s Chamber. In this instance, we must first understand what, from the perspective of Colonel Vyse, occurred when this chamber was first opened, and shortly thereafter:

“…The chamber above Nelson’s (afterwards called Lady Arbuthnot’s) was opened, and in the course of the afternoon I entered it with Mr. Raven… Lady Arbuthnot’s Chamber was minutely examined, and found to contain a great many quarry-marks. Notwithstanding that the characters in these chambers were surveyed by Mr. Perring upon a reduced scale, I considered that facsimiles in their original size would be desirable, as they were of great importance from their situation, and probably the most antient inscriptions in existence. I requested, therefore, Mr. Hill to copy them…” 17

Here we learn that Vyse first entered the chamber only with Raven, before commissioning Perring to undertake a plan survey of the painted marks he allegedly found there. We also learn that Hill was asked to make 1:1 facsimile drawings of the marks.

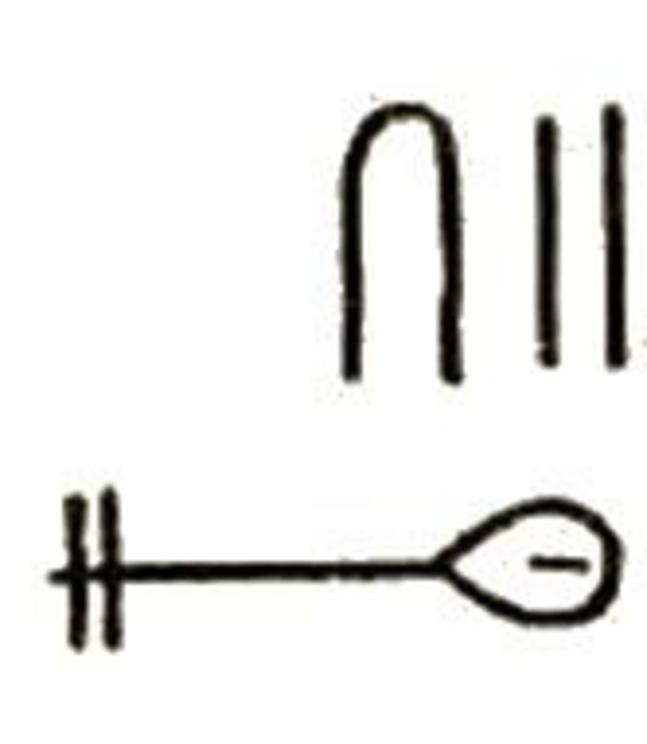

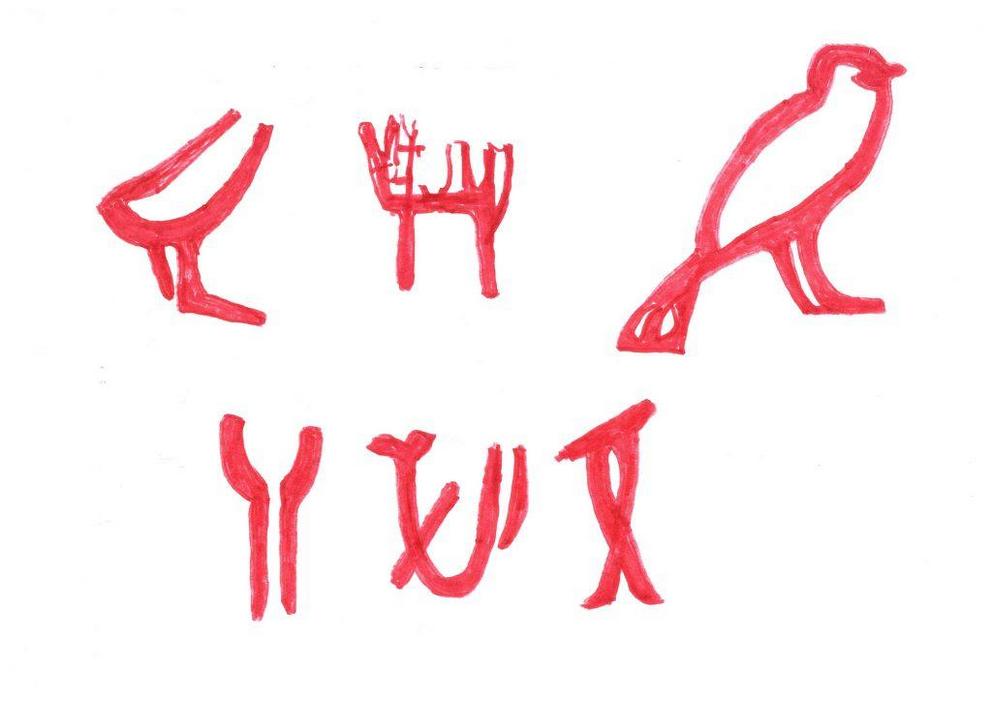

In the course of his survey of Lady Arbuthnot’s Chamber, Perring copied the following marks from one of the wall blocks:

Figure 7. Impression of the marks copied by Perring from Lady Arbuthnot’s Chamber. Note that the sign on the 2nd row, furthest right, is the only sign in this group of marks that is upside-down.

As explained earlier, each individual sign within a group of signs on a particular wall block within the ‘Vyse Chamber’ bears the same orientation whether that be upright, upside-down or sideways.18 However, the symbol included in Figure 7 demonstrates something quite unique—all of the symbols on the two rows of the script on this block are upright with the exception of one: the very last symbol on the second row is, bizarrely, upside-down.19

This is not something we would expect an ancient Egyptian scribe to have written, especially given that this upside-down sign on this wall block is not actually necessary for this particular inscription. The first five signs are believed to represent the name of a work gang: ‘The gang, Pure Ones [of the] Horus Medjedu’.20 The sign for ‘gang’ in this inscription is crudely written upright on the second row (far left).21 This means that the upside-down sign on the same row (far right), which also means ‘gang’, is anomalous and superfluous to this inscription.

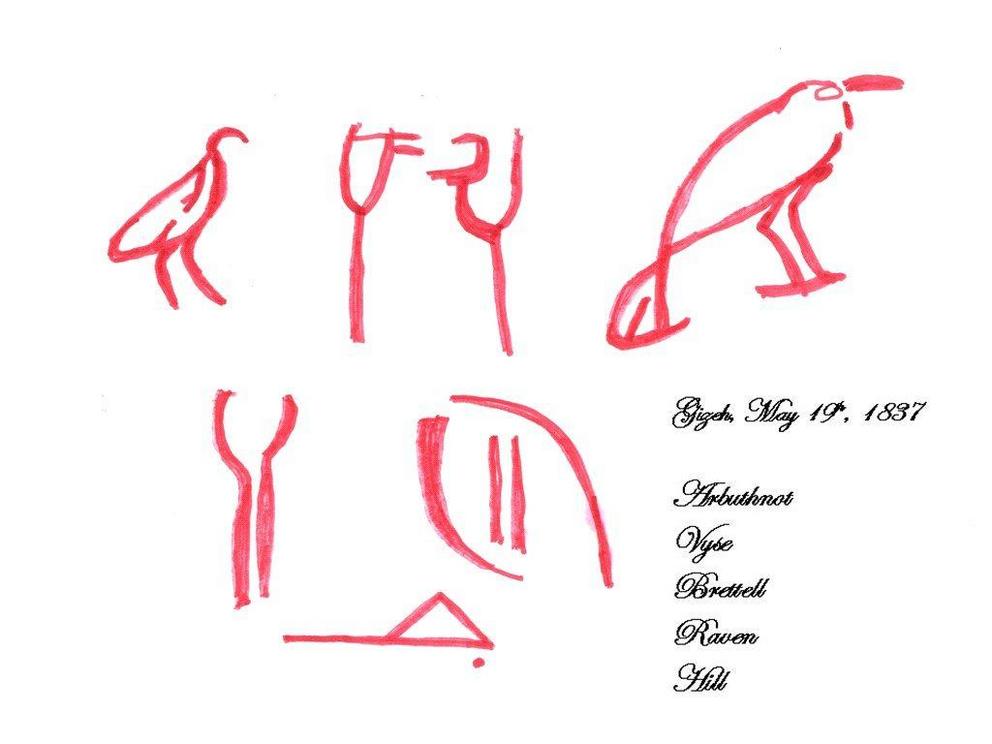

But what is even more peculiar about the inscription on this particular block is Hill’s 1:1 facsimile drawing of it; a drawing which Hill would have made within a day or even within hours of Perring’s drawing of the same marks: 22

Figure 8: Impression of Hill’s facsimile copy of the marks from the same block as Perring’s. Note the five witness names signed on the drawing.

There are a number of differences between the drawings made by Perring and Hill of the marks on this block, but the most significant difference is that the bizarre upside-down sign we observe in Perring’s drawing is entirely missing from Hill’s and in its place are five witness signatures (Figure 8).

What happened to it?

This particular symbol is a well-known and well-documented, bona-fide ancient Egyptian hieratic sign, and it is produced with the same upside-down orientation a number of times elsewhere in the ‘Vyse Chambers’.23

Suspicions arise

First, we are expected to believe that Perring copied a well-documented sign upside-down on the block, which is superfluous to the inscription and entirely out of place among the other upright signs on the block. Then, we are expected to accept that by the time Hill came to copy the anomalous symbol, it had vanished.

Furthermore, two weeks later, on 19th May 1837, Vyse arranged for no less than five witnesses to attest to the accuracy of Hill’s facsimile drawings against the block marks in the chambers.24 Notably, Mr Perring was not among these five witnesses.25

What are the chances that the most anomalous symbol painted in these chambers just also happens to be the only symbol to have mysteriously vanished from the inscription? What could have caused it to disappear like this?

Could it be that someone realised this mistake—this mismatch of sign orientations on this wall block— and had the sign removed from the block before Hill made his copy of it, but not before Perring had made his copy of these marks?

Critics of the fraud theory try to explain this anomaly away. First, it is suggested that poor lighting conditions (candle or oil lamp) may have resulted in Perring copying a symbol that wasn’t on the block.26 This explanation is highly improbable; if this were true, we would likely find other significant inconsistencies between the work of Perring and Hill, and we don’t.

Perring would have spent a fair bit of time observing and copying these marks; it is one thing to miss a small detail that does exist, but quite another to observe and copy something that simply doesn’t exist. Moreover, if Perring did somehow copy a non-existent sign, it is highly unlikely that it would be meaningful (i.e. an understood, bona-fide hieratic symbol) as opposed to unrecognisable squiggles that poor lighting could produce.

Critics of the fraud theory also point out that we do not have Perring’s original drawings, but only the lithographer’s rendition of Perring’s original artwork. 27 It is hence inferred that a mistake was made at some point during the production of the lithographic block used to impress these drawings.28

Once again, this objection does not stand up to scrutiny. The lithographic blocks would have been made in reference to Perring’s original artwork. It is the lithographer’s job to ensure an accurate lithograph is made from the original artwork. These lithographs (usually made of stone, hence ‘litho’) were not easy to make; the artwork would have been scrupulously referred to as each sign on the stone was cut and shaped.

Is it reasonable to expect that the lithographer could have made such an obvious mistake? And if they did make a mistake, would they have done so by including a symbol that wasn’t in Perring’s artwork?

Finally, the lithographs were for Perring’s book (as well as Vyse’s).29 As such, standard publishing practice will have ensured that proof copies were made and crucially, that they were approved by Perring before his book was published. It is inconceivable that this proof-checking would not have taken place.

If we accept that Perring made an accurate copy of what he observed in Lady Arbuthnot’s Chamber, then the disappearance of the anomalous symbol sets alarm bells ringing. There is seemingly no rational way to explain this disappearance other than to suggest that this erroneous symbol, this obvious mistake, was purposely removed from the block upon being realised—but, unfortunately for the forgers, as the evidence suggests, not before Perring had made his copy of it. This explains why Perring was apparently not invited to witness Hill’s drawings—he could have pointed out this glaring inconsistency.30

The deeper we investigate the marks in the ‘Vyse Chamber’, the more anomalies seem to arise. Egyptology can continue to ignore the considerable body of evidence that points to the perpetration of fraud in these chambers by Vyse and his team in 1837, or it can bite the bullet and put in place a program that analyses the inscriptions using transparent, non-invasive scientific methods.

Only then can this issue be settled.

The 'Edwin Smith' papyrus: a fine example of ancient Egyptian hieratic script and one of the world's oldest surviving surgical documents (c. 1600 BC).

en.wikipedia.org

For full references please use source link below.