Could the Epic of Gilgamesh, previously attributed to the Sumerians around 4,000 years ago...

...date back more than 10,000 years?

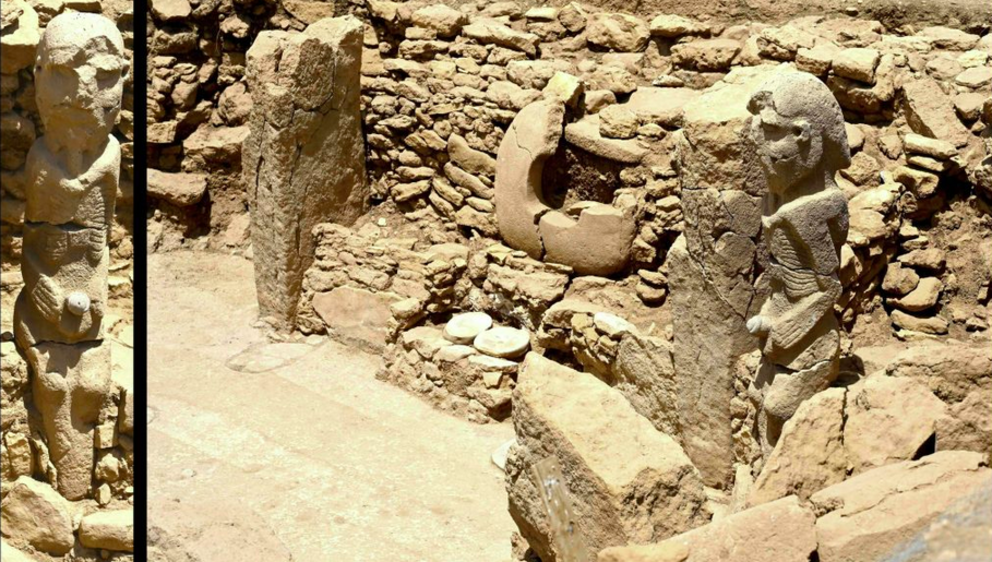

At Sayburç in southeastern Turkey, a few miles from the world-famous megalithic site of Gobekli Tepe, a very ancient engraved stone panel was excavated in 2021. The panel shows, from left to right, a charging wild bull, a man holding a serpent sitting or falling back before the bull, and a seated man holding his penis and flanked by two leopards.

After our flight to Istanbul took off from Baghdad International Airport I opened my laptop and re-read a research paper on the panel by Turkish archaeologist and art historian Dr Eylem Özdoğan. Titled The Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the Neolithic, the paper, was published in the authoritative peer-reviewed journal Antiquity in 2022 and contained a photograph of the eponymous scene which is carved into the vertical aspect of a knee-high stone bench. Dated to around 8500 BC, the scene has the “narrative integrity of both a theme and a story in contrast to other contemporaneous images,” says Dr Özdoğan. Indeed in her view it “represents the most detailed depiction of a Neolithic ‘story’ found to date in the Near East, bringing us closer to the Neolithic people and their world.”1

In the same folder where I’d filed Dr Özdoğan’s paper I’d filed the high-resolution photograph of the complete panel which the photographer, B. Kosker, had kindly released on Creative Commons:2

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

The scene seemed naturally divided into two parts so I had also made cropped versions of each “part”, as follows:

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Photo B. Kösker (CCBY4.0)

Before boarding our flight to Turkey my wife Santha and I had spent two weeks in Iraq, homeland of ancient Sumer, the world’s first literate civilization. Our primary purpose had been to visit the sites of ancient cities associated with the Sumerian Deluge legend.3 Paramount amongst these was Uruk with its origins dating back to 4000 BC or earlier, its great Ziggurat dedicated to the sky god Anu and it’s starring role in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh which itself contains a substantial discourse on the Deluge. I’d therefore been reading a good English translation of the epic along the way.4 Perhaps this was why a seemingly mad question suddenly began to clamour for my attention as I studied the photographs. Could the Sayburç reliefs have served as visual aids – a Neolithic version of PowerPoint slides – to accompany the recitation of an earlier unwritten incarnation of the story that we now know as the Epic of Gilgamesh?

What the Sayburç reliefs definitely don’t depict are simple hunting scenes. No hunter would take time out to masturbate while flanked by two snarling leopards – an “indifferent stance” as Özdoğan puts it, in the face of danger.5 And while wild bulls – aurochs in those times – were indeed hunted, a wall painting from the younger (7500 BC) site of Çatalhöyük shows the end of a hunt with an auroch subdued by a large number of armed men. Moreover, the creature is depicted as already dead, its tongue protruding, and thus no longer posing any threat. By contrast, observes archaeologist Jens Notroff, these are characteristics we do not find at Sayburç:

There, apparently, we see a still living animal, a still dangerous bull. At Sayburç we see a confrontation. Which leaves the question: What is the person actually doing here? Just like in case of the aurochs, its posture suggests dynamic and motion. Almost like an interaction — cocked legs as if the person is trying to dodge the approaching animal.6

Notroff hopes that the reliefs might help archaeologists better interpret Neolithic iconography in Turkey but adds:

Unfortunately, while the Neolithic hunter may have easily recognized its message we are still lacking an understanding of the actual narrative.7

In her Antiquity paper on the Sayburç reliefs Dr Eylem Özdoğan faces the same challenge. “The figures were undoubtedly characters worthy of description,” she writes:

The fact that they are depicted together in a progressing scene, however, suggests that one or more related events or stories are being told. In oral traditions, stories, rituals and strong symbolic elements form the foundation of the ideologies that shape society beyond spirituality.8

So maybe my mad idea wasn’t such a big leap? Dr Özdoğan had already put peer-reviewed authority behind the conclusion that the panel included a scene or scenes from an ancient story of some kind. But, like Notroff, she did not venture a guess as to which story it might have been. Gilgamesh had seemed unlikely to me at first because of the gap of more than 6,000 years between the Sayburç panel (around 8500 BC) and the earliest-surviving written recensions of the epic (around 2000 BC). But as I gave more thought to the matter, I realised that those six millennia didn’t necessarily represent an unsurmountable obstacle. After all, 3,000 years have passed since the time of Homer but the Odyssey (itself originally an oral not a written tale) is still being retold – for example in the 2024 film The Return.9 Meanwhile studies amongst Australia’s First Nations peoples and amongst the Kootenay of Oregon in the United States have proved that oral traditions still in circulation today accurately record and preserve information of significantly greater antiquity than Homer. Patrick Nunn, Professor of Geography at Australia’s University of the Sunshine Coast, summarises the conclusions of this research:

Under optimal conditions, as suggested by science-determined ages for events recalled in ancient stories, orally shared knowledge can demonstrably endure more than 7,000 years, quite possibly 10,000…10

There is, therefore, no a priori reason why the Epic of Gilgamesh shouldn’t be much older than its oldest-surviving written recensions, no reason why it shouldn’t have begun life around 8500 BC, the date of the Sayburç reliefs, no reason why it shouldn’t already have been ancient when the reliefs were made, and no reason why the story behind the reliefs should have been confined to the Sayburç area. Ancient communities were not hermetically sealed and Sayburç stands close to the headwaters of the Euphrates River just a few hundred kilometres from the borders of ancient Sumer where the Epic of Gilgamesh was supposedly “composed”. The possibility of a connection can’t be ruled out.

Pressure of other work meant that I didn’t see Dr Özdoğan’s 2022 paper on the Sayburç reliefs until the latter half of 2023 and it wasn’t until 2024 that I used my blog to set out my own first thoughts about the reliefs.11

What struck me most forcefully at the time was not only that this panel is indeed a contender for the role of the earliest-known depiction of a narrative scene, as Dr Özdoğan contends, but also that it is, unequivocally, the earliest-known depiction of a motif known as the “Master of Animals” that would become prevalent across vast expanses of the ancient world as far afield as Egypt and Peru, from about 6,000 years ago.

This very distinctive motif typically shows a man threatened by fierce animals, often felines such as lions and leopards, but sometimes by other wild creatures as well. In every case the individual at the center of the scene seems relaxed, unafraid and in complete control — hence “Master of Animals”.

As such the Sayburç scene looked to me – and continues to look — like a potentially fruitful link between prehistory and history, between those unnumbered aeons when it seems that nothing was written down and the last 6,000 years or so that have been dominated by the written word.

For the rest of this article please use source link below