Cambodia's exemplary centre of time and space

In 2012 I spent time filming a documentary in Peru and recently published a series of articles unfolding the sacred geography or the Inca Empire establishing their most important temple alignments and how their religious buildings synchronised with the passage of the sun on key dates in the Inca's agricultural, civic and ritual calendars.

In 2014 I travelled to Cambodia and spent time drawing parallels between Andean cosmovision; its resulting ceremonies, practices and animistic beliefs in objects having magical powers, and that of Vedic, Hindu and Buddhist cultures. With a private local guide, every morning before the tourists arrived, I was honoured to have been permitted to measure and photograph many of the most remote crumbling jungle temples of the Khmer empire. After a week acclimatising myself, my personal journey into understanding the sacred secrets of the Khmer Kings really began when I asked myself "where did the Khmer builder's cosmological, astronomical, geometrical and geographical themes and influences come from?"

Asking this question in Peru led me back in time thousands of years before the Inca empire to the religious beliefs, orientations, alignments, measurements and the greater sacred landscapes of the pre-Inca Tiwanaku civilisation. In this first article we will first learn about Khmer cosmology and how this world view influenced the creative faculties of the rulers, priests, architects and builders to construct the jewel in the Khmer crown - Angkor Wat. Then, we will travel back in time seeking the origins of this magical ancient cosmology which was born just after time began.

Ariel view of Angkor Wat looking east along the western causeway.

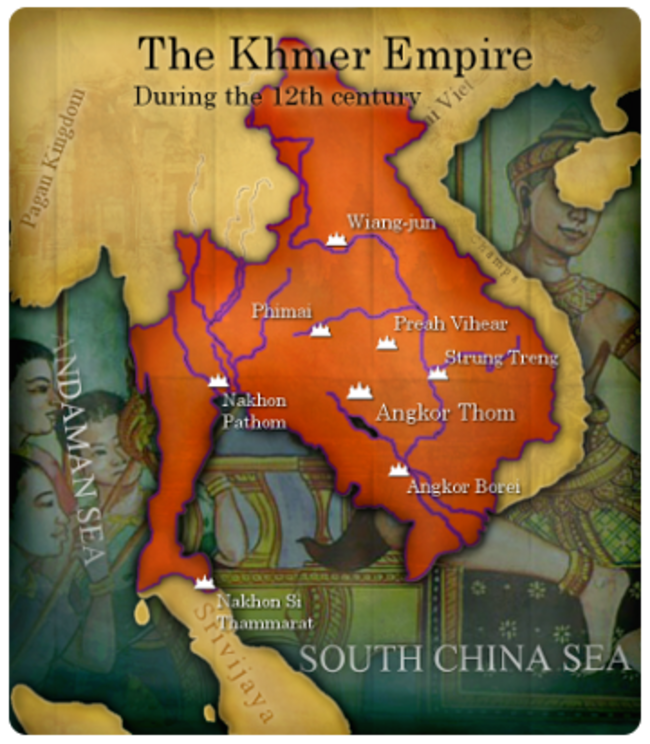

Between 879 - 1191 AD the Angkor Empire extended from what is now southern Vietnam to Yunan, China and westward to the Bay of Bengal. The great Hindu temple complex of Angkor Wat in modern-day Cambodia was built by Emperor Suryavarman II who reigned between AD 1113-50 on a scale repeated nowhere else on the planet, making Angkor Wat the largest religious monument in the world, with the site measuring 162.6 hectares (1,626,000 m2; 402 acres).

At that time London, England, housed around 18'000 people while Angkor Wat was a grand social and administrative metropolis, the largest city in the world, with over a million inhabitants.

Angkor Wat can be conceptualised as a heavenly portal on earth. At the very centre of the temple is the most sacred place in the complex, where humans and universal polar opposites united as a perceived column of creation energy flowing from the heavens and emanating from the temple outwards across the kingdom, thus effecting the fate of fields and humans.

Buddha busts lining the south entrance to the Angkor Wat complex. ©ashleycowie.com

CONTRASTING COSMOLOGIES

Followers of mainstream western religions worship an omnipotent creator who, standing outside of His creation, designed and built the universe within a week. The sacred architecture required to pay homage to this god demands open congregational spaces where groups of people gather, pray and to listen to clergymen delivering sermons.

In stark contrast to this the Hindu timeline expressed in myths and temple architecture resonates closer with the modern scientific idea that the Big Bang was not the beginning of everything, but the start of a present cycle which was preceded by an infinite number of universes, and will be followed by an infinite number of universes.

Thus, the Khmer temple was a microcosmic expression of the Hindu cosmological universe. The daily worship of Hindus and Buddhists required pilgrimage to a temple culminating with praying and/or meditating at the centre of the temple where the human soul experienced transcendence from the endless suffering and repetition of birth and rebirth.

Prae Rup Temple, Angkor, is located just south of the East Baray, or eastern reservoir, and is featured in Part 2. ©ashleycowie.com

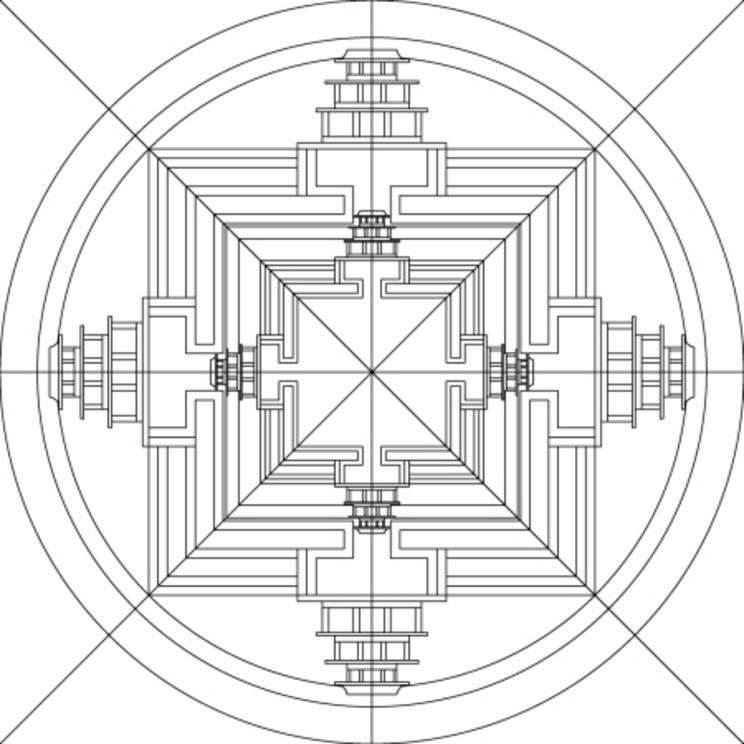

The “heavenly” state experienced at the centre of the temple was known as Nirvana in Buddhism and as Moksha in Hinduism. To enable and enhance the perceived spiritual experience Southeast Asian temples were designed first as mandalas - deeply spiritual symbols blending cosmological, religious and psychological motifs, which together represent the microcosmic and macrocosmic levels of the universe.

MANDALAS IN THE SKY

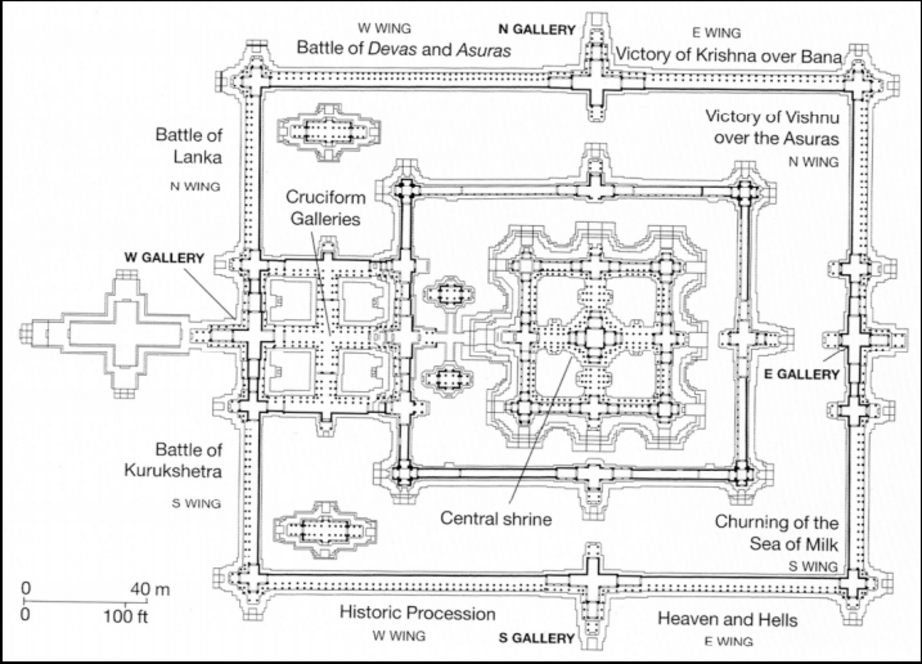

Mandala's were designed so that every proportion, space, area, ratio, length, breadth and height meant something deeper relating to Hindu cosmology. The fundamental/governing shape in all mandalas was a square, with concentric circles and T shaped gates on each face, all framing the mysterious centre point. Khmer Architects enlarged and reduced concentric squares, circles and triangles to achieve radial balance and to assure their designs were harmonically balanced, in all parts.

A mandala is a spiritual and ritual symbol in Hinduism and Buddhism, representing the universe. In common use, "mandala" has become a generic term for any diagram, chart or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically. ©ashleycowie.com

Upon completion, mandalas presented observers with a range of possible interpretations.

They were infinite libraries of esoteric and religious data, tools to aid meditation and geometrically sound plans for designing temple. Sometimes mandalas were created by large teams of priests brushing multi-coloured sand into place, but they were most often designed on paper or fabric and pinned on walls to help worshipers induce deep-state meditational traces.

At a rudimentary level within mandala design geometers faced a perplexing occurrence. No matter how large or small they expanded or contracted a concentric design, the centre point remained the same. The fixed centre point and this entire geometric organising principle was seen as highly esoteric and perfectly expressed Hindu cosmological ideas of how humans interact with the greater universe.

From the largest outer square to the smallest inner square, mandalas, therefore cities and temples symbolically embodied the universe, the world, the kingdom, the capital city, the temple, the individual and the soul.

Angkor Wat is arranged around a series of mandala's interlinked to represent ever more complex cosmological and esoteric themes. ©ashleycowie.com

Stone temples designed as mandalas had square nested walls forming processional pathways, corridors and passages carved with stories about the adventures and challenges of deities. At the centre of the temple was the axis mundi (world axis) - an invisible column of sacred energy connecting the heavens with earth, down which the gods were thought to pump spiritual energy into the earthly kingdoms, assuring prosperity.

Thus, when a ruler announced the construction of a capital city they were essentially creating a new “exemplary centre” - a prosperity generator - assuring a continued emanation of divine energy from the centre of the temple into the capital city and outwards across the kingdom.

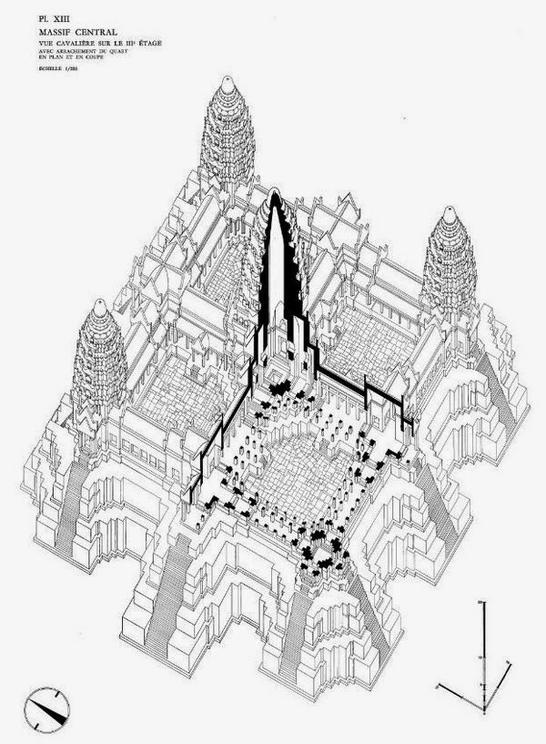

For thousands of years mandalas were expanded horizontally in two dimensions in attempts to bring the astronomical frame of the universe into a cosmological scheme. Khmer temple designers and builders introduced a third dimension by vertically expanding squares into stepped pyramids with central towers.

The concentric squares of the central 5 towers at Angkor Wat. ©ashleycowie.com

This evolutionary step in sacred architecture refocused the point of divine contact from the horizontal plane beneath our feet to the highest point in a structure which better expressed the Hindu-Buddhist belief that mountains, mountain ranges and caves were the sacred homes of the Gods. The mandala underlying Angkor Wat causes the entire temple complex to rise up forming a perfect square of four towers, which frame a centre tower, symbolising Mount Meru - the home of the gods.

We will examine the mythological aspects of Mount Meru and Angkor Wat in greater detail in forthcoming articles.

THE ORIGINS OF KHMER cosmology

Over the following articles we will see how the Khmer Kings extended their cosmology across the greater landscape, but before doing so we must first appreciate the essential hands on skills of the designers, architects, engineers and builders.

The cosmological and astronomical aspects of Angkor Wat originated in the ancient Indian Vedic traditions of altar and temple design. To truly understand the astronomical formats, and resulting rituals, at Angkor Wat we must first unravel ancient rope crafts and measuring skills of ancient Vedic Indian altar and temple builders.

My last book, A Twist in Time, explores the lost world of ropes in pre-history and tells the story of how the practical field crafts of ancient Egyptian rope pullers and measuring specialists became formalised by Greek mathamaticians into the sciences of geometry and mathematics. A Twist In Time, 2016:

"The Sulbasutras are early Hindu religious tracts written around 800 B.C.E but evidence suggests earlier versions were composed around 1500BC. The word 'sulba' means string, rope or cord, and the closest English translation of the word 'sutras' is ‘codes’. The Sulbasutras (rope-codes) detail how to create Vedic ceremonial structures, especially sacrificial fires, at different times of the year. They also detail the practical skills and techniques required to measure and construct in a systematic and logical way using ropes."

Archaeological evidence points to an advanced knowledge of rope crafts and geometry in the pre-Vedic culture, the Harappans, which pushes the origins of formalised rope geometry on the Indian subcontinent to well before 2000 BCE.

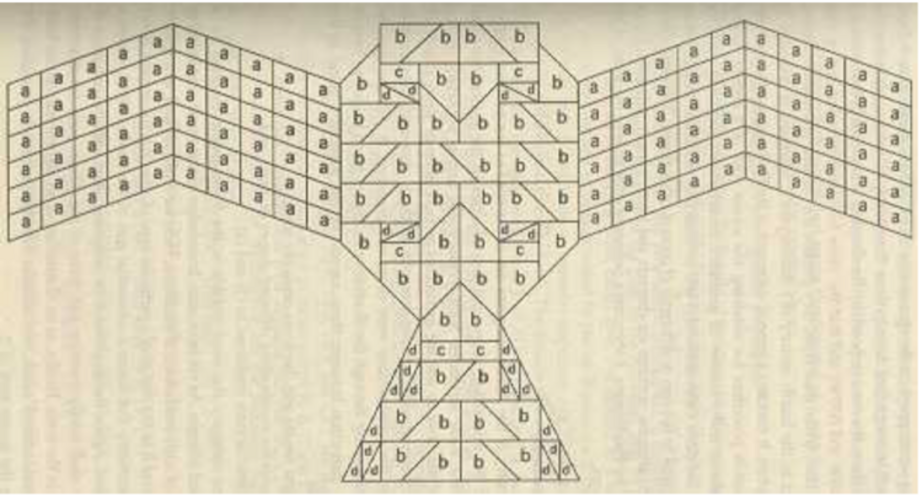

The first layer of a Vedic sacrificial altar is shaped like a falcon

Determining a location for constructing an altar (vedi) and the orientation and alignment of sacrificial fires, as well as their shapes and areas, were strictly managed in order that they "made effective instruments of sacrifice." Unique fire-altar shapes were associated with gifts from the Gods. For example; he who desires heaven is to construct a fire-altar in the form of a falcon; a fire-altar in the form of a tortoise is to be constructed by one desiring to win the world of Brahman and those who wish to destroy existing and future enemies should construct a fire-altar in the form of a rhombus.

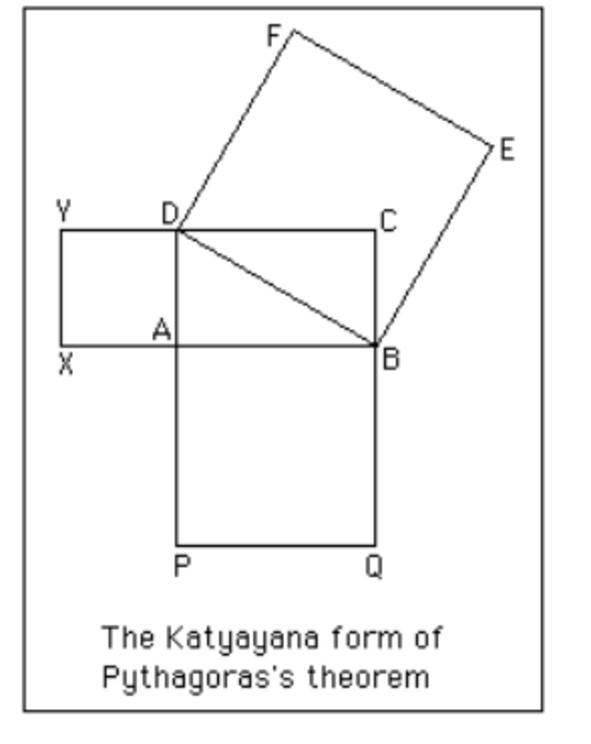

The rope which is stretched across the diagonal of a square produces an area double the size of the original square.

The Sulba Sutras were written mainly for the benefit of rope craftsmen laying out sacred buildings and altars, but they also contain a general statement of the Pythagorean Theorem. In addition to this they contain an approximation procedure for obtaining the square root of two, correct to five decimal places, an approximate squaring of the circle with rope. And, how to create rectilinear shapes whose area is equal to the sum or difference of areas of other shapes. The Bodhayana version of the Pythagorean Theorem is illustrated in the opposite diagram.

There were three principal types of cosmic fire-altars which were surrounded by 360 enclosing stones. The earth was represented by a circular altar surrounded by 21 enclosing stones, the sky was a square altar surrounded by 261 stones and the space altar was surrounded by 78 stones.

The ancient mathematical problem of squaring the circle was regarded as a deeply esoteric exercise where the sacred geometer spent sometime a lifetime attempting to unite the earth and the sky in geometric formats. The above listed sacred numbers all appear at a fundamental level at Angkor Wat and in most Hindu temples.

SACRED lengths and building modules

Angkor Wat’s foundational geometry expresses Vedic ideas relating to not only the microcosm and macrocosm but also to calendric time and cosmological concepts. Adhering to ancient principals of sacred architecture temple designers took numbers from natural cycles and cosmological ideas and converted them into lengths and building units, which were regarded as sacred measurements and divine building modules, respectivley. Angkor Wat’s sacred measurements were based on multiplications and divisions of the Cambodian cubit or hat (0.43545 m).

Traditional Khmer calendars, chhankiteks, were lunisolar - based on the movement of the moon but synchronising with the solar year to avoid seasonal drift - which was accomplished by adding an additional month or day to a particular year. The days in a solar year were represented by lengths of 360, 365, or 366 units. Days in lunar months (naksatras) were lengths of 27, 28, 29 units and a lunar year was 354 days. Two good examples of lunar and solar day counts being converted into lengths and integrated into the architecture of Angkor Watt are;

Full moon rising above Angkor Wat. ©ashleycowie.com

LUNAR GEOMETRY

The number of days in a lunar year was 354 and the distance between the Naga balustrade and the first step at the end of the walkway, to the upper elevation, is 354 meters.

SOLAR GEOMETRY

Solar numbers are present in the external axial dimensions of the topmost elevation of the central tower, which is 189.00 cubits east to west and 176.37 cubits north to south. Together they have a the sum of 365.37 almost exactly the length of the solar year.

CONCLUSION

Only a handful of academic and amateur historians have studied the complex relationship that existed between the Khamer conception of the world and how the rulers, priests and architects organised the greater landscapes surrounding their 'exemplary centres'. This is the focus of article 3, but next, in article 2, we will unfold the influence of Hindu creation mythologies on the iconography and architecture of Angkor Wat.

For continuation of this series please use source link below.