Bones of contention: the return of Mungo Man

The fact of his life far exceeds our sense of historical time.

In many ways, Mungo Man is more alive than dead.

For those who know him as an ancestor, his life and death 42,000 years ago are not distant.

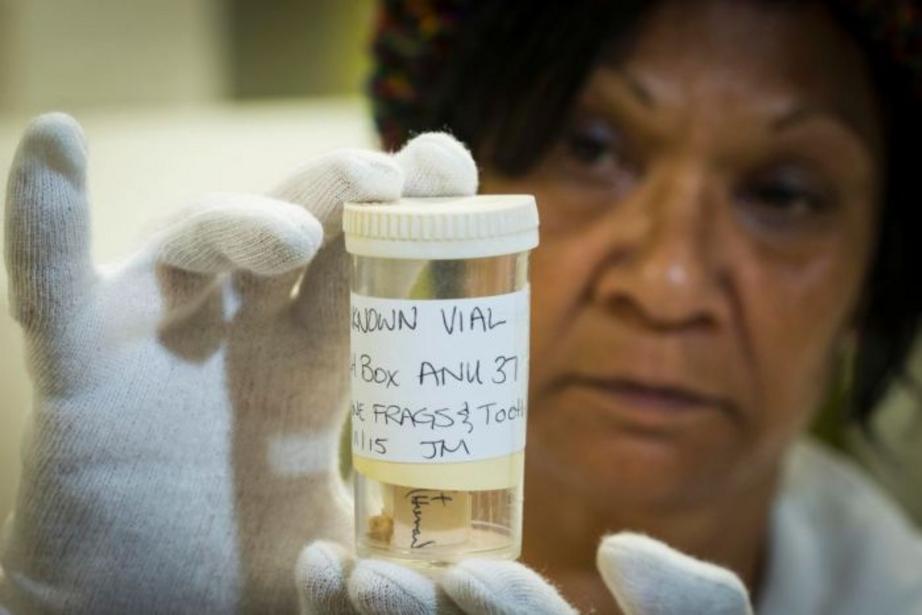

Maureen Kelly Reyland, a Mutthi Mutthi traditional owner from Balranald, holding a vial containing ancestral bone and tooth fragments at the ANU in Canberra. (image courtesy the Australian National University)

His burial was a ceremony involving the ritual use of ochre - the first in human history.

Apparently simple gestures, such as the way his body was arranged with his hands folded and his fingers interlocked, suggest a complex way of life that incorporated a system of belief.

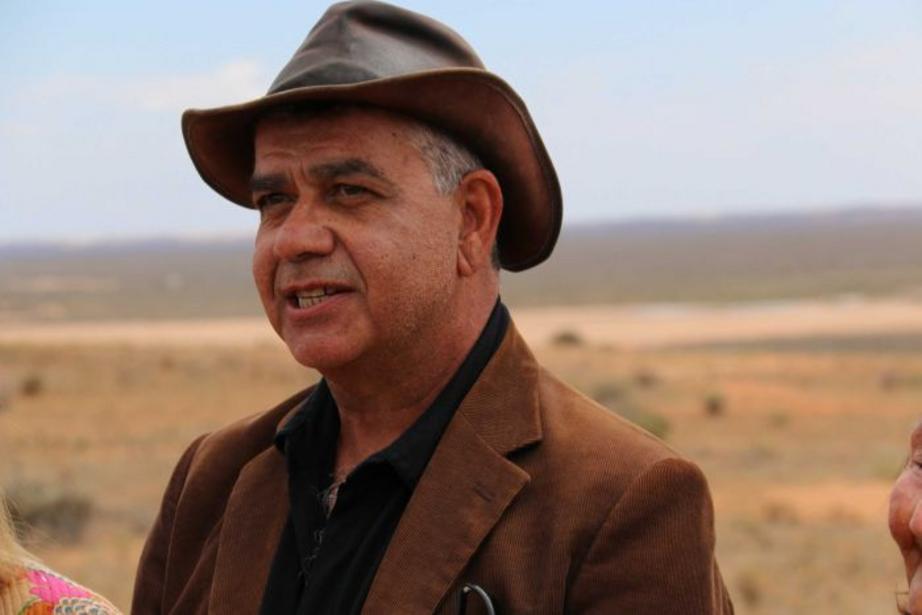

Michael Young, a Paakantyi and Parindji man and member of the Aboriginal Advisory Council, speaking at the repatriation ceremony at Lake Mungo. (ABC/Isabella Higgins/Bridget Brennan)

The fact he was taken from his grave in the shore of a dry lake in south-western New South Wales has been a source of pain for the three tribal groups who assert ownership of the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area.

His repatriation to his country is not the end of the story.

For instance, what do we do with his remains if they can't be safely reburied in the windblown, eroding sands of Lake Mungo?

A casket holding the remains of Mungo Man was hewn from 8000-year old redgum. (ABC/Isabella Higgins/Bridget Brennan)

TOP IMAGE: A whirly-whirly moves across a soft claypan inside Lake Mungo. (image courtesy Wayne Quilliam Photography)