Archaeologists reveal findings of Prittlewell Anglo-Saxon burial

Previously hidden secrets and insights into the Prittlewell princely burial and the man buried have been painstakingly reconstructed by a team of over 40 archaeological experts.

The new research published today by archaeologists from MOLA, and funded by Southend-on-Sea Borough Council and Historic England, explores the internationally significant collection, including hitherto unidentified artefacts from the Anglo-Saxon princely burial chamber.

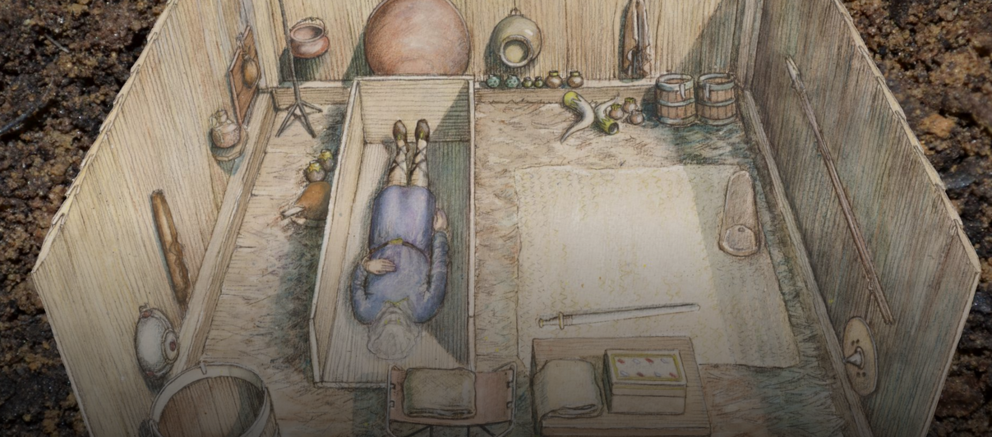

A reconstruction drawing of the Prittlewell princely burial chamber based on painstaking research(c) MOLA by HeritageDaily

In 2003 archaeologists from MOLA excavated a small plot of land in Prittlewell, Essex. The discovery of a well-preserved burial chamber adorned with rare and precious objects astounded archaeologists but many of the burial chamber’s secrets lay concealed beneath centuries of earth and corrosion, only to be revealed as conservators and archaeological specialists began their meticulous work.

Drinking vessels in situ within the burial chamber Credit : MOLA

Sophie Jackson, MOLA’S Director of Research & Engagement, said: “This is one of the most significant Anglo-Saxon discoveries this country has seen and because of the meticulous attention to detail given when excavating and recording the Prittlewell princely burial, a team of specialists has been able to reveal new elements of the burial chamber, details about the man buried and insights into Anglo-Saxon traditions that we never thought possible.”

Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England, said: “This burial chamber was an exciting discovery in 2003 and over the years it has slowly been giving up its secrets. The range of exquisite objects discovered here, now around 1400 years old and some of them representing the only surviving examples of their kind, are giving us an extraordinary insight into early Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship and culture.”

Previously concealed objects and facts that have been revealed include:

Anglo-Saxon musical instrument

The lyre (Old English hearpe) was the most important stringed instrument in the ancient world; this is the first time the complete form of an Anglo-Saxon lyre has been recorded.

The wooden lyre had almost entirely decayed save for a soil stain within which fragments of wood and metal fittings were preserved in their original positions. Micro-excavation in the conservation lab revealed that the instrument was made of maple with tuning pegs made of ash.

Using Raman spectroscopy specialists determined that the garnets in two of the lyre fittings are almandines, most likely from the Indian sub-continent or Sri Lanka. Extraordinarily, this treasured lyre had been broken in two at some time during its life and put back together using iron, gilded copper-alloy and silver repair fittings.

A reconstruction drawing of the Anglo Saxon lyre featuring the delicate repair work and garnet fittings c MOLA.jpg

1400-year-old colour painted box

This unique find is the only surviving example of early Anglo-Saxon painted woodwork. Originally lifted by archaeological conservators in a block of soil, detailed micro-excavation in the lab exposed hidden fragments of a painted maple-wood surface believed to be from a box lid.

The design includes a yellow ladder-pattern border that resembles the borders seen on Anglo-Saxon goldand-garnet jewellery, as well as two elongated ovals, one in white and one in red with cross-hatching perhaps representing fish scales.

Unique 1400 year old painted wooden box, the only surviving example of early Anglo-Saxon painted woodwork – Credit : MOLA

Britain’s earliest Anglo-Saxon princely burial

Scientific dating has revealed the burial most likely dates to the late 6th century, making this the earliest of the dated AngloSaxon princely burials. During the excavation it was not known whether collecting enough organic material to date the burial would be possible but sufficient material was collected in the lab from items such as a drinking horn to secure radiocarbon dates by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry.

The modelled radiocarbon date for the burial was narrowed to AD 575-605 and further refined by coins to a date after AD 580. This is a remarkably early date for the adoption of Christianity, as attested by the presence of Christian symbols within the grave.

The fittings on the two drinking horns provided vital organic material for successful radiocarbon dating. They gave date ranges for the death of the animal whose horns were used – Credit : MOLAS

An Anglo-Saxon prince?

The new dating evidence again throws the identity of the man buried into question. We can be certain that it was a man of princely or aristocratic lineage from the items in the chamber but earlier suggestions that this could be the burial of the Christian King Saebert (died about AD 616) must now be ruled out. Experts believe it’s possible that he was the kin of King Saebert, perhaps his brother Seaxa, although there is no way to know for sure.

However, analysis of items found within the coffin have revealed exciting new details about the man. The presence of weapons and a triangular gold belt buckle reveal that this was a man, and the gold foil crosses, amongst other items, show he was a Christian. Tiny fragments of tooth enamel, the only remains of the skeleton to survive, reveal that he was older than six.

From the position of the tooth fragments, gold crosses probably placed over his eyes at one end of the coffin, with a gold belt buckle in the middle and garter buckles to fasten his footwear at the other end, we can now estimate that he was about 1.73m (5ft 8in) tall, indicating he was an adult or an adolescent.

Placed with his head to west, he may have been buried with a gold coin in each hand, with one hand on his chest and the other lying by his side.

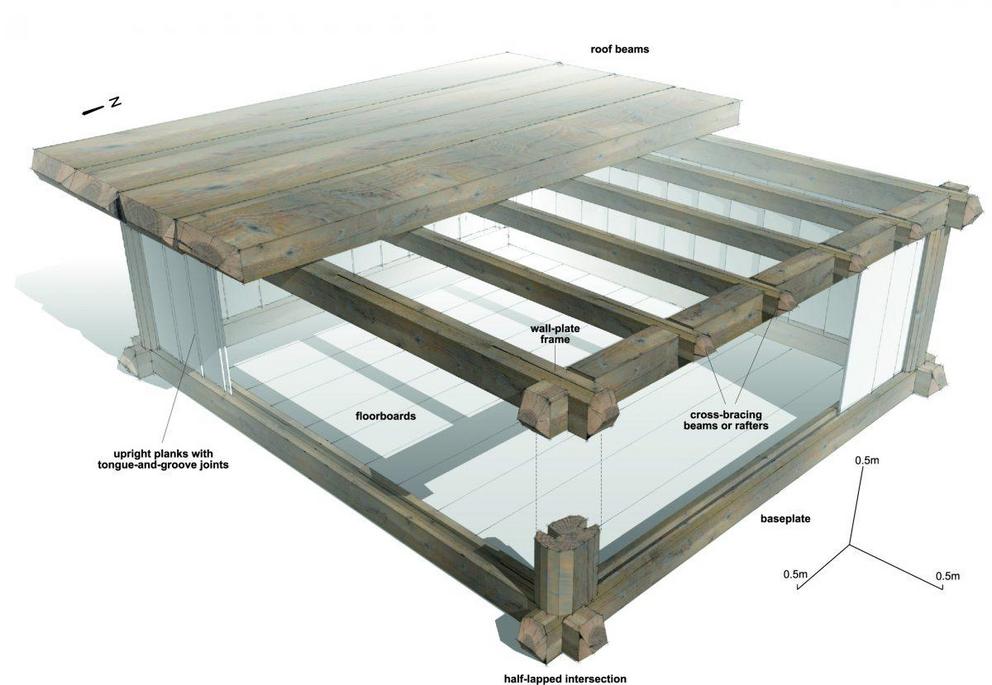

113 person-days to build a chamber fit for a prince

The original chamber timbers decayed, leaving only stains and impressions of the structure in the soil for archaeologists to investigate.

Back in the lab specialists managed to find more evidence, including mineral-preserved wood surviving on iron wall hooks, from which they skilfully recreated the chamber design.

A detailed reconstruction of the timber structure of the Prittlewell princely burial chamber based on organic evidence on items within the chamber – Credit : MOLA

Working with engineers, the team calculated the resources needed to construct the chamber. Requiring about 113 person-days’ work, the chamber represents a huge investment in skilled labour, as well as materials.

Led by archaeological experts from MOLA, the work was funded by Southend-on-Sea Borough Council and Historic England. The research was undertaken by leading experts in a range of specialisms, including Anglo-Saxon art and artefacts, ancient musical instruments, ancient woodworking, engineering and soil science.

Copper-alloy bowl made in Britain and discovered still in position hanging on the chamber wall – Credit : MOLA

The team left no stone unturned, using a range of techniques – from soil micromorphology and CT scans to Raman spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy and mass spectrometry – in their quest to reconstruct and understand the chamber as it would have been on the day of the burial.

For the first time objects from the Prittlewell princely burial will go on permanent display at Southend Central Museum. Open to the public for free from Saturday 11 May 2019, the new permanent gallery features some of the chamber’s most impressive items, including a gold belt buckle and gold-foil crosses made specially for the burial, a Byzantine flagon and basin, an ornate drinking horn, a decorative hanging bowl and coloured glass vessels.

One of two rare blue glass decorated beakers. The two were almost certainly made as a matching pair and discovered in tact within the burial chamber – Credit : MOLA

About MOLA:

MOLA provides independent archaeology and built heritage advice and professional services. With offices in London, Northampton, Basingstoke and Birmingham, MOLA’s 300 staff helps to discharge planning conditions expertly and swiftly. MOLA works in partnership to develop far-reaching research and community programmes.

Header Image – A reconstruction drawing of the Prittlewell princely burial chamber based on painstaking research(c) MOLA