60 percent of primates sliding toward extinction

A comprehensive study looking at more than 500 species of primates finds that most are declining in numbers and nearly two-thirds face the threat of extinction.

Gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans – our great ape cousins teeter on the precipice of extinction. And it’s not much of a secret that we humans have had a lot to do with putting them there.

But what about the other primates? The news isn’t much better, it turns out.

According to a new study, 60 percent of primates – including drills and gibbons, lemurs and tarsiers, bush babies and spider monkeys – face the threat of extinction. Even those not in immediate danger of dying out are at risk, as the numbers of three-quarters of all primate species are trending downward.

“The figures suggest that we may be reaching a tipping point or perhaps we are already there,” said Alejandro Estrada, lead author of the study and a senior research scientist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, in an email to Mongabay. He and 30 other primatologists published their research Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Estrada said that he and fellow author Paul Garber of the University of Illinois noticed that, for all the research on specific primates in specific areas, what was missing was a broader understanding of conservation and threats for all primates.

But that’s not an easy undertaking. Primates are a huge and diverse group with 504 species by the authors’ count. The only other mammal orders with more species are the bats and the rodents.

The team began by pulling together information from published research, the IUCN Red List, and UN databases to puzzle out where primate populations are headed and why.

http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com

http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com

Pied tamarins (Saguinus bicolor), which are listed as Endangered by the IUCN, are restricted to around 900,000 hectares of habitat around Manaus, Brazil – an area that has seen significant land cover change over the past decade. Data from the University of Maryland and visualized on Global Forest Watch show the region lost around 6 percent of its tree cover between 2001 and 2014, and its Intact Forest Landscapes – areas undisturbed and large enough to retain their native biodiversity – are fragmented and degrading. Photo by Stavenn via Wikimedia Commons (CC 3.0) / Range approximated based on data from the IUCN

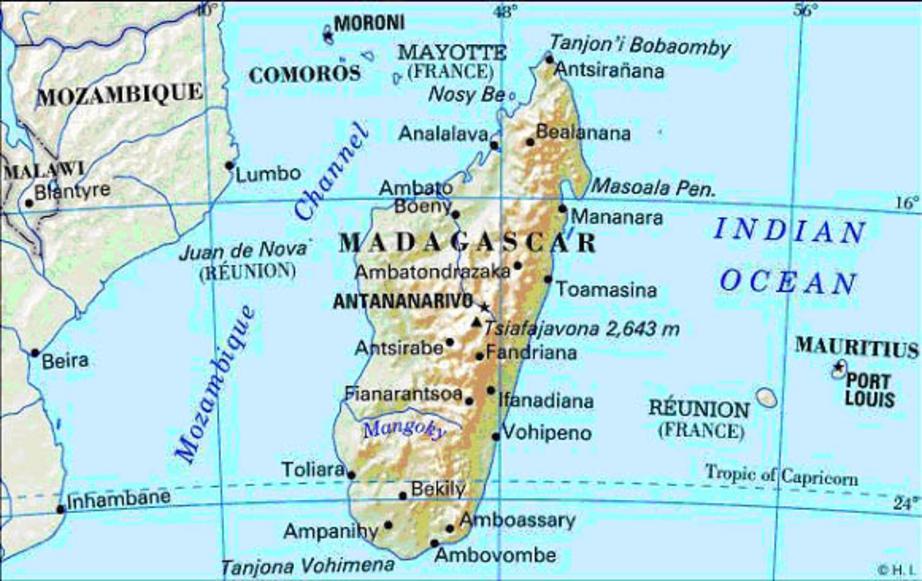

The researchers tabulated the threats, statuses and conservation efforts for primates in 90 countries across Central and South America, Asia, mainland Africa, and Madagascar.

“What was surprising from our global analysis is that many species in the four regions are threatened and a higher number have their populations declining,” Estrada said.

For example, nearly 90 percent of Madagascar’s more than 100 primate species are threatened.

Apes in Asia aren’t faring much better, as anyone who studies orangutans will attest. Around 73 percent of primates there face an uncertain future, and the global demand for palm oil has pushed the two species of orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus and Pongo abelii) to the brink of extinction in Southeast Asia.

The statistics for primates in the Americas and continental Africa are marginally less dire as a whole. A little more than a third are considered threatened. But hidden in those figures are extreme cases, like the roughly 900 remaining mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei).

Monkeys and apes in Africa and Central and South America face the same increasing dangers that have driven down numbers elsewhere in the world. At the top of the list is the expansion of agriculture, which threatens 76 percent of all species worldwide, the researchers write.

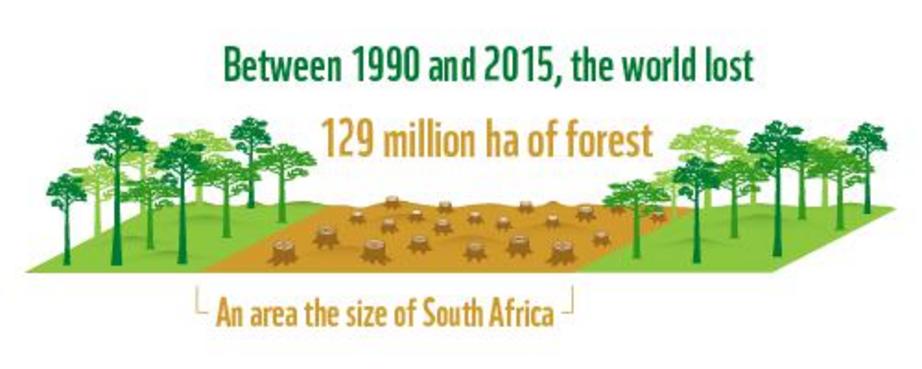

Between 1990 and 2010, we humans took over around 1.5 million hectares (about 5,790 square miles) for farming – three times the size of France. And forest cover loss, which is critical habitat for many primates, was even greater at 2 million hectares (7,722 square miles), according to the study.

Logging and ranching have also opened up huge areas that were once primate domain.

And it’s not just the complete destruction of ecosystems that causes problems. When pastures, farms and plantations wedge into primate territory, it can leave groups of the same species on increasingly disconnected islands of livable space. The authors report that we’ve carved up – or fragmented – almost half the world’s tropical forests and 58 percent of its subtropical forests.

“Ultimately, the biggest threat is loss of habitat, without a doubt,” said Martha Robbins, a primatologist at Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who was not involved in the research. “I don’t think it should be a surprise to anybody that, with increasing human population growth and increasing human consumption, we are just using more and more habitat.”

Robbins praised the extent of the research, adding, “It does an excellent job of summarizing the state of primate conservation.”

In particular, she was happy to see that the team had teased apart not only the direct causes leading toward the extinction of certain primates, such as hunting, which threatens 60 percent of primates (and many other mammal species). They also drilled down to the underlying causes for those activities, such as the pervasive human poverty often found around areas where primates live.

With that framework, the authors put forth more than a dozen potential approaches that could help staunch primate declines, ranging from lowering the market demands in richer countries that enable the trade of primates to campaigns aimed at the next generation on the importance of protecting these animals.

“Deforestation, unsustainable hunting and illegal trade could be rapidly addressed via education programs applicable to children, young adults and adults,” Estrada said.

But it can’t be just a one-off investment, he said. “This approach would need to be continuous over the long-term, rather than being a short-term effort.”

Robbins pointed out the paradox with many of these keys to protecting primates.

“In some ways, the solutions are extremely easy,” she said. “Don’t chop down the forest, stop illegal trade in animals, find ways of reducing disease.

“All of the solutions in and of themselves are very obvious. It’s just implementing them and really making a change is what is so difficult.”

The study also revealed that for many primates, data is scarce, Estrada said. Even now, scientists are still coming across undiscovered species, like the recently unveiled Skywalker gibbon (Hoolock tianxing), a mountain-dwelling ape that lives in China and Myanmar.

“Our arsenal of scientific knowledge on the natural history, ecology, behavior and biology for most primate species is particularly poor,” Estrada said. “There is an urgent need for many more field studies to gain a clear understanding of species flexibility when faced with anthropogenic threats.”

Global primate species richness, distributions, and the percentage of species threatened and with declining populations. Image courtesy of Alejandro Estrada (Estrada et al. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1600946)

A big question mark for primatologists is how their study subjects will respond to climate change. In a step toward finding some answers, Estrada and his colleagues compiled a phylogenetic analysis of 340 primates – the largest-ever look at the underlying connections between primate species ever undertaken.

“Usually, closely related species share aspects of their basic biology, such as body size, reproductive physiology, diet, behavior and even geographic distribution,” Estrada said. “Such relatedness may make species sensitive to, for example…natural shifts in the distribution of their habitats, or to human pressures resulting in habitat reduction or loss, hunting, [or] climate change.”

Based on these connections, scientists may be able to use what they know about one species to predict how a threat might impact another.

“Due to their low population numbers and the intensity of threats, we may soon have a cascade of human-driven primate species extinctions,” Estrada said. The new research underscores an urgent need for more nuanced understanding of primates, while at the same time addressing the barrage of pressures we humans level at them.

Estrada said he’s optimistic about our chances of success, but he remains realistic: “We are running out of time for much of this.”