Two deaths, zero accountability: Indonesia’s mining pits claim more lives

- Two boys drowned in a rain-filled mining pit in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province in early September, highlighting once again the danger posed by abandoned pits.

- Police have ruled the deaths accidental, but a mining watchdog plans to file a criminal complaint against the mining company, PT Sarana Daya Hutama (SDH), for failing to rehabilitate the site at the end of its operations, as required by law.

- There are more than 1,700 of these abandoned pits throughout East Kalimantan, Indonesia’s coal-mining heartland, which have claimed 39 lives since 2011.

- The companies behind them are rarely ever punished; the only one to be prosecuted was fined the equivalent of just 7 U.S. cents.

On Sept. 6, five teenagers went together to a man-made lake in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province, carved out of a coal-mining pit that had been abandoned and filled up with rainwater. It was a popular recreation site for the locals, thanks to its sparkling blue water.

But that day, only three of the teens returned home. The two others, Muhammad Aryo Putra Satria and Rizky Setiawan, drowned while trying to swim to a raft in the middle of the lake.

“I’m devastated. I can’t say anything,” Sahrul, Satria’s father, told Mongabay. “Any parent would feel the same thing if it happened [to them].”

Satria was 14, and an only child. He was a keen athlete, with ambitions to play soccer beyond school. Now, he and Rizky have become statistics, the latest in a growing list of people — mostly children — to die in the abandoned mining pits peppered throughout eastern Indonesian Borneo.

Since 2011, there have been 39 recorded deaths in abandoned pits, according to the Mining Advocacy Network (Jatam), a watchdog group. There are at least 1,735 of these pits dotted across East Kalimantan, Indonesia’s coal-mining heartland, with 64 of them in the district of Paser, where Satria and Rizky died.

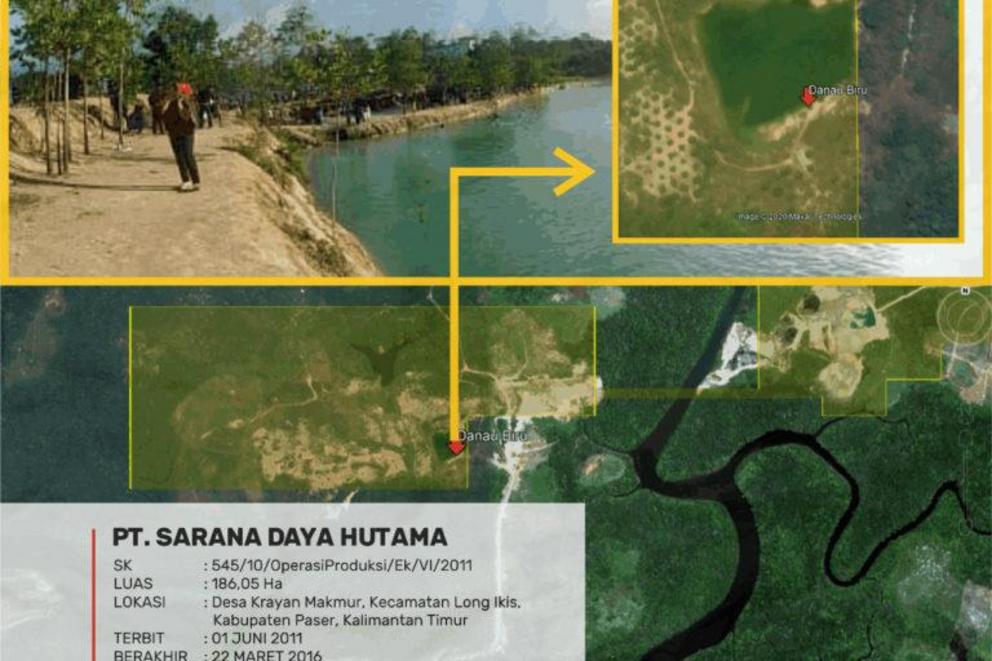

That particular pit is located in the former concession of mining company PT Sarana Daya Hutama (SDH). The company obtained a permit for the 186-hectare (460-acre) concession in Paser district’s Krayan Makmur village in June 2011. It ceased mining the following year, even though its permit was valid until March 2016.

The pit that it had dug up and abandoned gradually filled up with rainwater that took on a bluish hue — a common feature here due to the presence of heavy metals from the mining activity, which also turns the water slightly acidic. Due to their attractive colors, some of these pits have become tourism spots, including the one in the Krayan Makmur. The villagers call it Blue Lake, and it’s listed as a recreational site on Google Maps, with 12 mostly favorable reviews that call it “beautiful,” “clean,” and “awesome.”

The rain-filled mining pit turned tourist attraction, Blue Lake, in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Two boys died from drowning in the pit in September 2020.

Gray area of accountability

The proliferation of these pits-turned-tourist attractions came after Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources issued a regulation in 2014 allowing former mining pits to be used for various purposes, including fish farming, irrigation, and tourism.

The regulation came despite existing laws requiring mining companies to rehabilitate their concessions after operations end. But the framework of rules governing Indonesia’s mining sector is riddled with loopholes and blind spots that allow companies to shirk this obligation.

That means that when incidents occur at abandoned pits, like the drowning of Satria and Rizky, it’s difficult to know who to hold accountable.

Yusuf Sumako, head of the Paser district tourism agency, said the lake in Krayan Makmur wasn’t officially listed as a tourist attraction and thus didn’t fall under the purview of his office.

The Paser police chief, Murwoto, suggested no one would be held accountable for the deaths of the two teens.

“The blue lake is an open area,” he said. “The incident is not intentional. We deem it as a pure accident.”

As with most of the other lakes that have sprung up from mining pits, there are no warning signs or security guards at Krayan Makmur’s Blue Lake, says Jatam. The lake is also not fenced off, despite this being one of the requirements in an integrity pact signed in 2016 by the East Kalimantan provincial government and 125 mining companies operating here.

Pradarma Rupang, from the East Kalimantan chapter of Jatam, said the police’s decision to rule Satria and Rizky’s deaths as accidental effectively absolves mining company SDH of any responsibility. He said Jatam plans to report the company to the police for its failure to properly rehabilitate the mine after use, and thus endanger lives.

Azwar Bursa, the head of the provincial mining department, said his office would launch an investigation, including a review of SDH’s reclamation planning document, which details the company’s post-mining plan, to see if it really intended to turn the mining concession into a tourist attraction at the end of operations. Azwar added that SDH had not relinquished the concession to the provincial government despite having ended its operations in the area in 2012.

“So the company has to take responsibility,” he said.

But even if found to have violated its obligation to rehabilitate the site, SDH only faces the possibility of meaningless administrative sanctions: a written warning; a temporary closure of the site, which it abandoned eight years ago; or a revocation of its permit, which expired four years ago.

“The company is no longer in operation, so we’re a little bit confused,” Azwar said, acknowledging the toothless nature of the sanctions.

Punishments are rare, and there’s only one record of a case like this winding up in court. That was the case of PT Panca Prima Mining, in whose abandoned mining pit two children died in December 2014. The verdict in the case: a two-month prison sentence for the company’s security officer and a token fine of 1,000 rupiah, or about 7 U.S. cents.

Jatam director Merah Johansyah said he’s skeptical that authorities will follow up on the SDH case.

“There’s no hope,” he told Mongabay. “Because behind [the company] is a very rich tycoon. Would the government dare to enforce the law [against the company]?”

The location of the Blue Lake mining pit in Paser district, East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

The location of the Blue Lake mining pit in Paser district, East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

Who’s behind the mine pit?

PT Sarana Daya Hutama’s corporate registration papers suggest it’s controlled by the Tanoko family, which has business holdings spanning food and beverages to real estate to paints and cosmetics.

The majority stakeholder in SDH is PT Wira Laju Rejeki (WLR), a company with ties to the Tanoko family. Members of the family serve as directors of both SDH and WLR.

SDH’s office is located in the headquarters of the Tanoko family’s paint business, Avian Paint, in Surabaya, East Java. The phone number listed in its registration document is the same as that for PT WITA Internasional Bisnis Artisan, a mining and plantation subsidiary of Avian Paint. When Mongabay called the number, the operator said SDH is a part of WITA.

“The pit isn’t without its owner. There are parties who are responsible,” Jatam’s Merah said. “The company’s registration document already shows the identities of the directors, shareholders and board members. Now the government only has to chase them. The government needs to check whether the company has a reclamation planning document or not. And if there is, what was the reclamation plan? Was it really for tourism?”

Merah said that despite the lack of punishment for companies like SDH, authorities are at least moving to seal off the abandoned pits that have claimed lives.

In 2015, the East Kalimantan governor at the time, Awang Faroek Ishak, issued a decree temporarily halting the operations of 11 companies in whose mining pits children had drowned. The decree also instructed the companies to erect warning signs and fences around the pits.

Merah attributed these actions by both the government and the companies to the fact that the problem was being amplified in the media, generating immense pressure for action from not just the families of the victims but also the general public. But the government and companies have been much less responsive recently, he said, with no efforts to close down open mine pits and rehabilitate pits that have been abandoned.

“We haven’t heard of any effort to enforce the law [by the authorities],” Merah said. “There hasn’t been any attempt to seal [SDH’s mine pit] even though it’s been nearly two weeks since the incident.”

He said the current governor of East Kalimantan, Isran Noor, should step up and take action, given the growing number of children dying in abandoned mining pits under his watch.

Isran has responded to the issue in the past by saying the victims were fated to die that way. He also suggested the abandoned pits were haunted.

“I myself am baffled” by the number of deaths, Isran said as quoted by Kompas daily. “Maybe there are many ghosts [there]. Why are there many child victims?”

Merah said Isran’s statements and the government’s lack of action showed the people were effectively on their own, with little hope of justice for the families of the victims.

“We haven’t heard anything [since Satria and Rizky’s deaths],” he said. “There’s no statement from the governor or the district head. The public has to see this and engrave in their memory that this is how the government is taking care of its people, which is by doing nothing.”

The rain-filled mining pit turned tourist attraction, Blue Lake, in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, claimed the lives of two boys who died from drowning in the pit.

The rain-filled mining pit turned tourist attraction, Blue Lake, in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, claimed the lives of two boys who died from drowning in the pit.

‘We have to accept it’

In the long term, the government’s inaction will claim more lives, which makes it tantamount to “an extraordinary crime,” Merah said. “These pits aren’t caused by natural events. They are the legacy of companies and should have been closed and rehabilitated. We can’t narrow down the problem by saying that it’s a mere accident.”

He also called on the government to be consistent about enforcing the law, regardless of who was behind the companies.

“Even if they are rich, the law still applies to them,” he said. “The law can’t be picky because this tragedy keeps repeating. There are already 39 victims. We’re like a calculator, we keep on counting [the number of victims]. But these are people’s lives we’re talking about.”

For Sahrul, the father of 14-year-old victim Satria, the threat posed by abandoned mining pits is part of the reality of life here in Indonesia’s coal country.

“Nobody knows when they’re going to die,” he said. “Suddenly, Satria had to go. We have to accept it. May he rest in peace.”