Shinrin-yoku: a deep dive into forest bathing

Even indoor plants can have a positive effect on your mental health.

A friend from France once said the best lunch in Paris is a baguette, cheese, a bottle of wine and a park bench. She didn’t know it, but she had hit on the concept of a preventative form of nature therapy called shinrin-yoku, which was introduced half-a-world-away in Japan in 1982.

Translated literally, shinrin-yoku means "forest bathing." Forest bathing doesn’t mean you take a bath in the forest, of course; rather, you simply go for a leisurely walk in the woods — or a city park if a forest isn’t handy — where you relax by using all your senses to experience nature.

Yoshifumi Miyazaki, deputy director of the Center for Environment, Health and Field Services at Chiba University in Japan, is among a growing number of scientists who have begun studying the science behind the physiological and psychological effects of nature on human health and well-being. Their studies have focused on the effects of forests but also have included the effects of urban parks and gardens and even indoor plants.

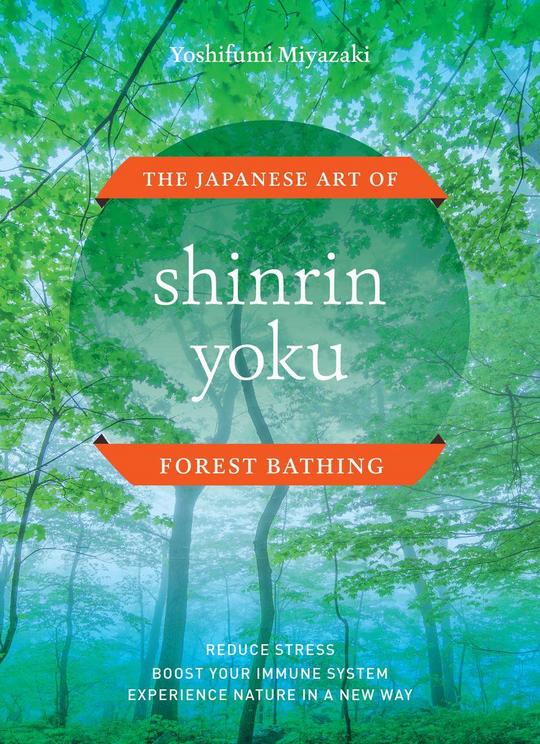

In his book "Shinrin yoku: The Japanese Art of Forest Bathing" (Timber Press, 2018), Miyazaki explains the techniques of forest bathing, how it reduces stress and stress-related diseases and boosts the immune system and the science behind these results.

Miyazaki has an interesting theory about why shinrin-yoku is so effective. He points out that for more than 99.99 percent of the time since our ancestors set out on a path that led to the present human condition, humans have lived in a natural environment. In fact, he contends that we’ve only lived in urban settings for a few hundred years, a timeline he suggests begins in the middle of the Industrial Revolution.

"In 1800, only 3 percent of the world’s population lived in urban areas," according to the book. By 2016, he writes, this figure had reached 54 percent. This is only going to get worse; the United Nations Population Division predicts that by 2050, 66 percent of people on the planet will live in urban areas.

The image that emerges from his studies is that "we live in our modern society with bodies that are still adapted to the natural environment." This is true, he writes because "genes cannot change over just a few hundred years." The science behind the research studies he presents in the book make a compelling case that the concept of forest bathing is an effective method for reducing stress in today’s crowded, computer-driven communities in which humans are becoming increasingly stressed in their quest to cope with the demands of daily life — a task for which they are genetically unprepared.

Forest bathing in a city

If you live in a city, parks are a great way to surround yourself with nature.

If you live in a city, parks are a great way to surround yourself with nature.

The problem with living in cities in bodies adapted to nature is that this lifestyle keeps "the sympathetic nervous system in a constant state of over-stimulation," according to Miyazaki. Fortunately, the solution doesn’t require a full-blown forest, which that might not be easily accessible for many.

In urban settings, parks make an acceptable substitute. City planners around the world are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of nature and are creating new kinds of "parks" out of derelict spaces that have become popular destinations. Examples include the Highline, a former elevated rail line in New York City; the BeltLine, a series of abandoned rail lines that circle Atlanta and are being turned into walking trails; and the Seoul Skygarden, a former highway in Seoul that now boasts 24,000 plants.

To test the theory of whether a literal walk in the park is indeed relaxing, Miyazaki tested 18 male Japanese university students who took 20-minute walks in Shinjuku Gyoen, a famous park in Tokyo, the most populous city in the world, and in an urban area around the Shinjuku transit station. The results showed the experience in the park physically relaxed the test subjects through an increase in parasympathetic nerve activity, which Miyazaki says is known to increase relaxation and a lower pulse rate.

Other pockets of nature in cities and urban communities include community and city gardens where you can have your own vegetable plot and botanical gardens. For kids, kitchen gardens in schools are becoming increasingly popular. And, Miyazaki emphasizes, you don’t have to find a formal park or garden to practice shinrin-yoku. You can enjoy "the wonderfully relaxing effects of nature to improve … health and well-being," as Miyazaki puts it, any place where there are plants and access to a path.

Forest bathing at home and work

Plants in your work space can help lower stress levels.

Plants in your work space can help lower stress levels.

Better yet, he says, we can bring nature closer to where we spend most of our time — at home and at work. Miyazaki’s research, for example, has shown that just increasing the amount of wood in a room can affect the relaxation benefits of the room. He conducted blindfold tests and asked people being tested to lay their palms on squares of white oak rather than a kitchen worktop for 90 seconds. "If the wood was untreated, the subjects experienced reduced brain activity, increased parasympathetic nervous activity, reduced sympathetic nervous activity and lower heart rate, all signs of relaxation."

Simple houseplants or flower arrangements can have a similar effect. To prove this, he conducted tests using nature therapies involving ornamental plants, bonsai, flower arrangements, floral scents and wood scents. In all cases the results were similar, even when people simply looked at flowers, their bodies relaxed and stress levels decreased.

The heads of the Finish Forest Research Institute and the Center for Health and Global Environment at the Harvard School of Public Health have contacted Miyazaki about how to merge their research with faculties in medical schools. He sees this as key challenge for the future of forest bathing — how to combine the research into physical things such as forests and timber with further research involving people. He believes scientists are in a transitional phase to accomplishing that goal.

In the meantime, he believes that in the modern world, forest therapy and other nature therapies are the most practical ways to reduce stress levels, increase relaxation and reduce the strain on healthcare services all over the world. "At the end of the day," he writes, "our bodies are adapted to nature."

Additional reading

If shinrin-yoku sounds like something you want to learn more about, here are some additional books about trees and nature immersion to consider:

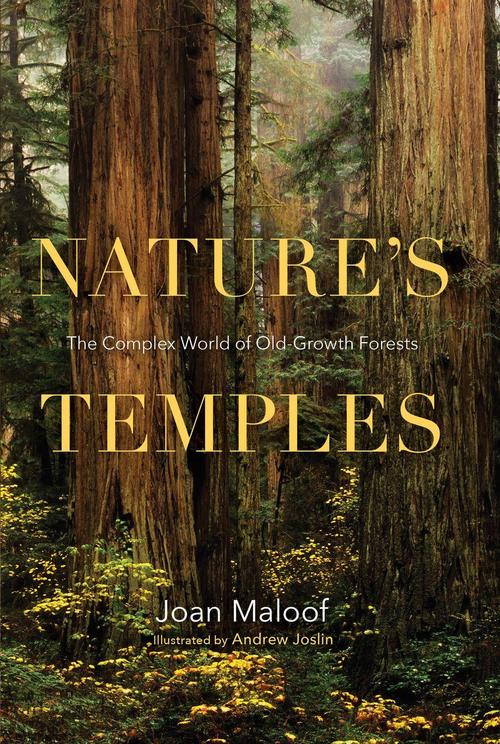

"Nature’s Temples, The Complex World of Old-Growth Forests," by Joan Maloof (Timber Press, 2016). Old-growth forests truly are nature’s temples because, as Maloof points out, not every forest reaches "old growth" status. In Georgia, for example, Andres Villegas, president and CEO of the Georgia Forestry Association, says the state is on its third forest. While acknowledging that there are different definitions for the term, Maloof describes an old-growth forest "as one that has escaped destruction for a long enough period of time to allow natural biological and ecosystem functions to be the dominant influence." That can take hundreds of years in much of North America or thousands of years in the redwood forests of California. Only remnants of these original forests remain, but, if you're lucky enough to walk in one, Maloof’s book will help you understand why these "Temples of Nature" are “inextricably connected to our planet, our fellow species, and lift our spirits."

"Nature Observer, A Guided Journal," by Maggie Enterrios (Timber Press, 2017) On one level, this is a journal to record your observations on nature walks, but it's also so much more. Enterrios’s drawings throughout the pages are a delight unto themselves. She also offers pages for you to draw your own images as you practice shinrin-yoku in a forest or park. There are places to track sunrise and sunset in your neighborhood, to record the dates of when trees in your yard or your neighbors' yards begin to bloom or to record the types of birds you see on a daily basis and during migrations. It’s also a teaching guide to help you learn leaf shapes and the trees they come from. Finally, there are places for notes to write down the ways nature has influenced your day. At the end of the year ,you’ll have a keepsake of the favorite places you visited and how your intensely personal connections with nature have influenced your life.

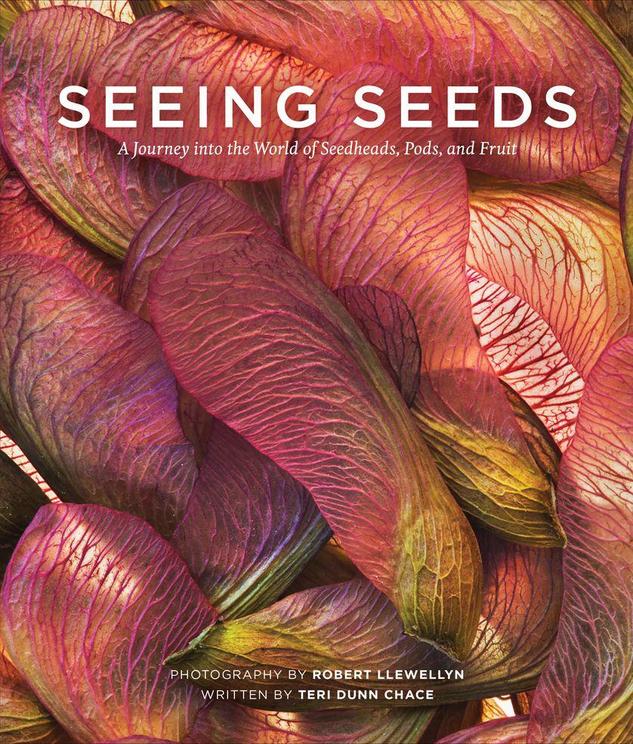

"Seeing Seeds, A Journey into the World of Seedheads, Pods, and Fruit," by Teri Dunn Chace (Timber Press, 2015). Chace believes a life force is embedded in simple seeds, and we as humans are co-evolutionary with them. "No seeds equals no fruit or nuts. Without seeds to nourish them, animals and birds would struggle or perish. Without seeds to nourish us, farms and foraging would dome to an end. Human beings would be endangered." In this book, which highlights 100 representative seeds, fruits and pods, you’ll gain an understanding of how seeds are formed, why they look like they do and how they are dispersed. And you will never look at a seed the same way again.

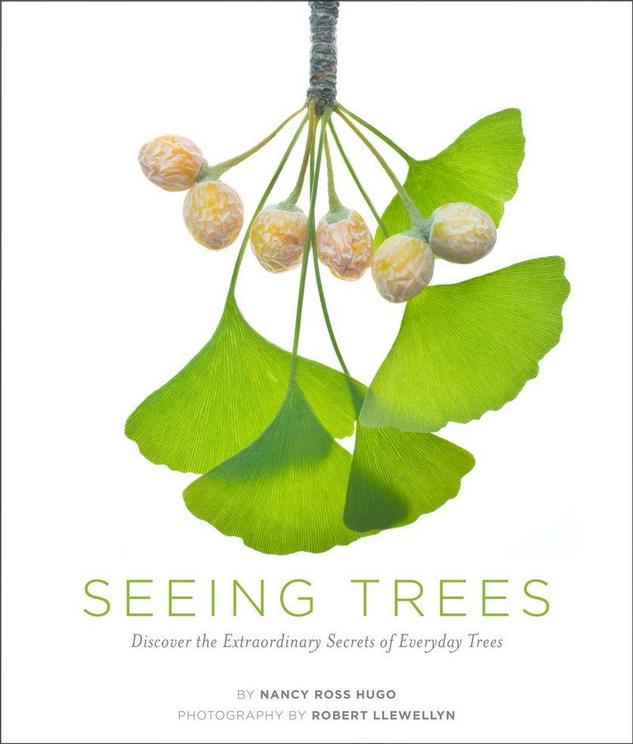

"Seeing Trees, Discover the Extraordinary Secrets of Everyday Trees," by Nancy Ross Hugo, Photography by Robert Llewellyn (Timber Press, 2011). You’ve heard the expression, "You can’t see the forest for the trees." In this book that provides in-depth profiles of 10 familiar species and references to many more, you’ll learn strategies to see trees like you’ve never seen them before. Instead of seeing them as inanimate objects, you’ll learn to see the details of leaves, cones, fruit, buds, leaf scars, bark and twig structure in ways that make observing trees as exciting as birdwatching — and knowing that it took trees 397 million years to evolve to their present state makes it all the more compelling. You might come to the same romantic conclusion as British naturalist Peter Scott: "the most effective way to save the threatened and decimated natural world is to cause people to fall in love with it again, with its beauty and its reality."