New soy-driven forest destruction exposed in South America

The watchdog NGO Mighty Earth followed up its February investigation into deforestation for soybean production and found that companies are sourcing from farms in Brazil and Bolivia where clearance is still occurring.

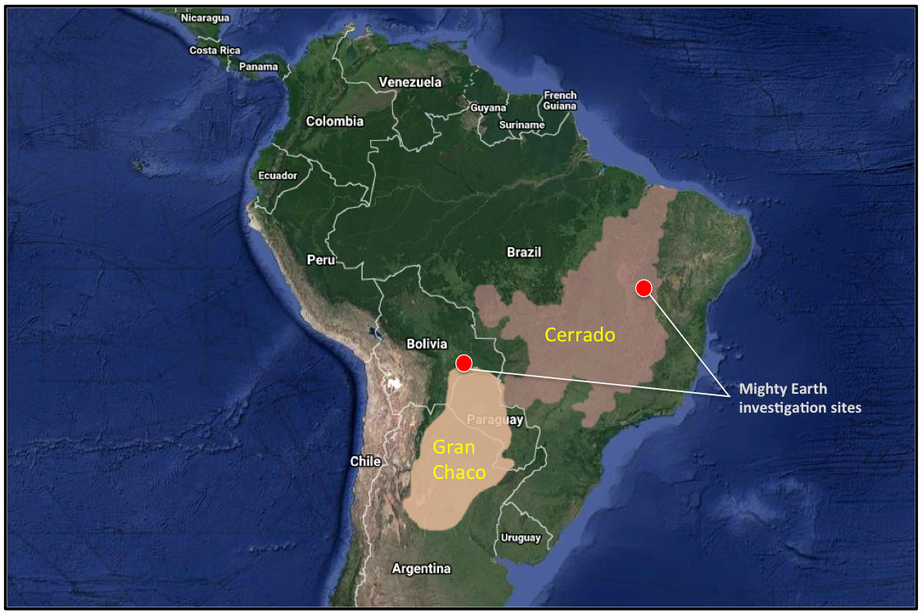

- Mighty Earth looked at updated satellite imagery from 28 sites in the Cerrado in Brazil and the Gran Chaco and the Amazon in Bolivia.

- They found evidence of 60 square kilometers of land clearing for soy production since their September 2016 investigation.

- Bunge and Cargill, the two companies that figure prominently in Mighty Earth’s latest report, argue that they are working to eradicate deforestation from their supply chains.

Companies are still getting their soybeans from the clearance of little-known forests and savannas in Brazil and Bolivia, according to a new report, despite calls to shift their focus to degraded or deforested land.

“It is completely unnecessary to clear new areas of native vegetation to increase soy production,” said Anahita Yousefi, campaign director at the Washington, D.C.-based Mighty Earth. “We were very surprised to see that [these companies] haven’t taken this more seriously.”

On May 18, the watchdog group released satellite images from 28 sites in the Bolivian Amazon, and the dry forests and savannas of the Cerrado in Brazil and the Gran Chaco in Bolivia. The land clearing that they document demonstrates that approximately 60 square kilometers (about 23 square miles) – larger than 10,000 American football fields – had been cleared to make way for soy planting since September 2016. Mighty Earth reported that these farms primarily sell their soy beans to Bunge and Cargill, two large international corporations based in the United States.

“These are companies that have publicly stated that they want to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains,” Yousefi said in an interview.

Mighty Earth’s investigation found soy-driven deforestation in lowland Amazon rainforest, as well as in the Cerrado and Gran Chaco biomes. Both biomes are comprised of a variety of ecosystems and are host to high levels of biodiversity — and both are threatened by encroaching agriculture. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), around 12 to 15 percent of the Gran Chaco has been cleared; that number rises steeply to around 80 percent for the Cerrado.

In February, Mighty Earth linked nearly 700,000 hectares (2,700 square miles) of deforestation and cleared land in the Cerrado between 2011 and 2015 to Bunge and Cargill. Much of that soy ultimately ends up feeding cattle to produce the beef sold by fast food chains like Burger King.

Bunge responded at the time that Mighty Earth made a “misleading” connection between total deforestation figures for the Cerrado and the company’s presence there. The company also argued that Bunge by itself wouldn’t be able to solve the issue.

Yousefi said that Mighty Earth took their findings to the companies, but they have not seen the immediate cessation of land clearing it had hoped for.

“They’re not really convinced that they need to do anything different to tackle this,” she said.

In response to requests for comment on the latest findings, both companies highlighted their pledges to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains and said that they have plans in place to accomplish that goal.

“We are expanding traceability of our supply, collaborating to develop new systems to identify areas for suitable agricultural expansion and exploring ways to provide new incentives to farmers to avoid deforestation,” said Stewart Lindsay, vice president of corporate affairs at Bunge, in an email.

Cargill too cited their involvement in tackling deforestation. “We have a proven track record protecting forests and are proud of our progress,” said Chris Schraeder, a spokesperson for the company, in an email. “Yet we know we have more work to do.”

Clearing continues

In central Brazil, the Mighty Earth team found that roads had been constructed on three soy plantations in the Brazilian Cerrado between December 2016 and January 2017. Yousefi said that the cutting of new roads is a strong indication that crews will soon clear the adjacent land. These farms supply both Bunge and Cargill.

Land cleared for soy production in the Bolivian Amazon. Photo by Jim Wickens / Ecostorm for Mighty Earth

Mighty Earth contends that evidence of road construction and other preparations for agriculture will likely mean the clearance of another 120 square kilometers (46 square miles) on the lands in question.

Satellite imagery from the edge of the Gran Chaco in Bolivia revealed 10 square kilometers (3.9 square miles) of clearance for soy at a site known as Menonitas 1 beginning in December. Mighty Earth said that Cargill confirmed that it buys soy grown on this land.

On the Papagayo Agropecuaria Celestina farm in the Bolivian Amazon, 4.7 square kilometers (1.8 square miles) has been cleared for soy and cattle since September 2016. The farm’s workers said that Cargill is one of their customers, but Cargill denied that claim when Mighty Earth brought it to them.

The Cerrado in Brazil. Photo by Alex Costa via Mighty Earth

Yousefi said that rates of agricultural conversion in places like the Gran Chaco, the Cerrado and the Amazon outside of Brazil often escape international attention.

“These are not areas where there has been a lot of public scrutiny into these operations,” she said, adding that efforts should be expanded to protect more of the Amazon biome. “This is the same ecosystem. It’s as valuable as the part of the Amazon that’s within the Brazilian borders.”

Cargill’s Chris Schraeder pointed out that his employer signed onto the Brazil Soy Moratorium in 2006. The agreement stipulated that companies would not purchase beans from suppliers that had cleared their land after July 2006.

Schraeder said the agreement is part of the reason that deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon have plummeted by 80 percent since 2004. The company is now involved in efforts to “advance forest protection” in the Brazilian Cerrado, which is modeled after the collaborations between industry, NGOs and government that led to Brazil’s soy moratorium.

Yousefi said that industry-wide action is exactly what’s needed and that using the successes in Brazil as a model provides companies such as Bunge and Cargill with the “toolkit available for them to deliver on their goals.”

“If you look at how relatively quickly the Brazilian soy moratorium was able to turn [deforestation] around,” she added, “it’s really unparalleled.”

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.