Mystical experiences might bridge the gap between LSD-induced 'madness' and healing

New study examines the paradoxical relationships between psychosis, psychotherapy, and psychedelic experiences

A new randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study helps to bridge the gap between previous research that had examined LSD as a model of psychosis and research on the therapeutic value of psychedelic drugs. The findings, which appear in the journal Psychological Medicine, suggest that mystical experiences are an important link between the psychosis model and therapeutic model of LSD.

“An amazing amount of research was produced on the psychosis model of psychedelics (such as LSD and mescaline) in the middle of the last century. Within the current ‘psychedelic renaissance,’ this model has almost been forgotten, since the focus is lying more on the therapy model and the question of how psychedelics can exert beneficial effects,” said study author Isabel Wiessner, a PhD candidate at the University of Campinas.

“I understand that it is tempting to approach this promising side of ‘healing’ since it helps researchers to justify the work with these still illegal substances and acquire funding. But I also think that we should not neglect this considerable body of knowledge on the ‘dark side’ of psychedelics. I wanted to dive deeper into this forgotten perspective of psychedelic-related ‘madness.'”

“There is a gap in modern psychedelic science in understanding the relationship between psychedelic effects and symptoms of psychoses,” added co-author Marcelo Falchi, who served as the study’s team psychiatrist. “There are also gaps in understanding which psychedelic effects allow for treatment, for which condition and under which nosological perspective. Furthermore, there is a gap of how the phenomenology of substance-altered perception and sense of self correlate with brain functioning in a visionary or psychedelic state.”

“While similarities exist between such non-ordinary states of consciousness – psychosis and psychedelia – our study also identified distinctions between them,” Falchi said. “I think that, once we have detailed cartography of the psychedelic state, it may be possible to plot a route on this map of unknown lands and seas in a safe way for clinical application. A route of understanding, both, its potentials and risks, free from moral and political judgments.”

In the study, 24 healthy adults with at least one previous experience with LSD participated in two experimental sessions, which were separated by 14 days. The participants received either 50 μg LSD (a relatively low dose) or an inactive placebo in the morning, and then completed a variety of psychological assessments throughout the day.

The researchers were particularly interested in examining aberrant salience, a psychological concept linked to psychotic symptoms. Aberrant salience describes the unusual assignment of significance to normally innocuous external objects and internal representations. For example, people experiencing aberrant salience might feel that the boundaries between their inner and outer sensations have been removed or feel that once trivial things have suddenly become important.

Wiessner noted that when LSD was initial distributed by the pharmaceutical company Sandoz in the 1950s, psychiatrists consumed the substance to better understand what psychotic experiences were like.

“I think this indication is still valid since the consumption of a psychedelic substance might open a completely new horizon of how we perceive the world. At least it can teach us health professionals some humble respect and empathy for people who are experiencing these perceptual alterations in their everyday life,” Wiessner explained.

“Interestingly, the paradox of how the same substance could mimic some psychiatric conditions and heal others had never been properly examined before. Specifically, I was fascinated by the question of whether both models eventually could be connected or reconciled in any way.”

The researchers found that LSD induced positive mood, alterations of consciousness, mystical experiences, ego-dissolution, and mildly challenging experiences. The substance also significantly increased aberrant salience. Importantly, aberrant salience was positively correlated with psychedelic experiences, particularly mystical experiences and ego-dissolution.

LSD also increased the tendency to react to suggestions. But this increased suggestibility was not correlated with other effects.

“Just as psychedelics can induce both, good and bad trips, we should be aware that they can also exert improvements in some clinical conditions (such as depression) and deterioration in others (such as schizophrenia),” Wiessner told PsyPost. “Our study found evidence for the validity of both models, demonstrating therapeutic- and psychotic-like effects in healthy subjects.”

“Moreover, our results indicate that there might be a connection between both models in the form of mystical experiences. Mystical experiences seem to play a key role in both psychotic and therapeutic experiences: they are commonly reported by people with psychotic disorders and have previously been shown to be crucial for psychedelics to exert therapeutic benefits (for example in anxiety or depression). In other words, LSD-induced mystical experiences might be the missing link between the psychosis model and the therapy model.”

Falchi, the head of the psychiatry unit at Biomind Labs, said that the findings provide evidence that mystical experiences play an important role in the healing process.

“Life dances in this beautiful tension between madness and healing, which inevitably harks back to shamanic healing processes and other age-old traditions in their understanding of healthy vs. unsuccessful existence,” he told PsyPost. “In indigenous cultures, there is no diagnosis of schizophrenia. Shamans who have extrasensory perceptions do not fulfill the criteria of low functionality of the manuals (DSM V, ICD 10, etc.), but are even better adapted to their culture.”

“Thus, it seems to me as elegant as obvious that we must integrate the sophisticated knowledge of recent Western medical science in the knowledge of ancient medicine from indigenous and other cultures, in order to better provide care for the suffering individual which is seen in all cultures (perhaps more in ours).”

But the study, like all research, include some caveats.

“Since we merely examined healthy subjects, we cannot tell whether our results are applicable to clinical populations,” Wiessner explained. “Specifically, future research should compare how mystical experiences play a role in psychotic and therapeutic experiences in different clinical conditions and whether mystical experiences are comparable in quantity and quality over these conditions.”

“As a psychiatrist, I must reiterate that the experiment is not a clinical trial,” Falchi added. “Therefore, the information contained therein cannot be extrapolated to patients who experience their body, brain, and mind (or consciousness) differently. To date, clinical studies have excluded psychotic populations, such as patients with (highly prevalent) psychotic depression, so in the future, such issues should be addressed. I emphasize that an acute psychotic state is distinguished from chronic psychosis, e.g., schizophrenia.”

Both researchers said that psychedelic experiences could play a pivotal role in reconceptualizing psychiatric diagnoses.

“Interestingly, another almost forgotten theory associates mystical experiences in psychosis with spiritual trances and shamanism,” Wiessner told PsyPost. “Although these ideas are not seriously discussed in contemporary psychiatry, they reflect a contrary perspective to the established psychiatric system. Similarly, modern approaches claim a shift from categorizing patients into disorders towards working with transdiagnostic, culture-specific, individual experiences. In other words, the diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder might be more a cultural concept than universally valid.”

“These considerations are fundamental when we look at whether LSD mimics or heals psychiatric disorders. Overall, the common denominator of mystical experiences seems to underlie these contrasting facets of “madness” and “healing”. This, in turn, implies that we need to closely examine mystical experiences. By this, we might better understand and eventually influence our mental health.”

“In a similar vein is the call of a Bewusstseinskultur (consciousness culture), which claims an integration of consciousness-related issues into our society on a holistic level,” Wiessner continued. “This might include teaching techniques to alter consciousness at school (e.g. meditation, hypnosis, lucid dreaming) and evoke a public dialogue on how to deal with artificial intelligence, psychiatric disorders, euthanasia and our need for altered states of consciousness.”

“Isabel and I share the same view on mental health,” Falchi said. “Psychiatry in the last century has been in a pendulum movement: In 1900, with the release of Freud’s ‘The Interpretation of Dreams,’ it orbited in the epistemology of mentalism (brainless) and as of 1950, with the discovery of the first antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine (Delay and Deniker), biomarkers of mental illness (neuroimaging techniques) and other drugs (Prozac), the pendulum touched the opposite diameter — psychiatry was seen as functional neurology: organicism (mindless).”

“I see psychedelic science as an elegant way to resolve this Cartesian duality that limits diagnosis, treatment, and mental health care. Psychedelic science seems to understand that we exist in a body, organic and material, therefore, with major hardware on which we operate, the brain, and from which emerges a superstructure or intangible epiphenomenon of another order, called consciousness and the realms of the psyche. From this, it unfolds to understand the subject in itself and for itself, organically and mentally, but beyond itself, a culturally engaged subject: the subject in relation.”

“I am concerned that the socio-economic-cultural model currently adopted as the only and ultimate one will negatively interfere with a more organic, complex, and broad process that is the validation of well-being, the perception of quality of life, and the very process of cure beyond the superficial symptomatic relief,” Falchi added. “I am referring to the post-industrial capitalist model of productivity, supremacy and cognocentrists. Therefore, it is necessary to have a historical look, in temporal cuts beyond what our life allows us to observe, and to understand that this is not the only one, it was not the only one, and it will not be the only or the best model.”

“When productivity is placed above other values, including humanistic ones, we see this explosion of mental disorders. But I am not a fatalist, much more a realistic optimist; I have to say that there are already airs of good omen coming from the great capitalists: there are already those who recognize that to maintain their “sacred” productivity, individual and shared well-being is necessary. Thus, I hope for the transition and incorporation of humanistic, ineffable, and culturally varied knowledge in our western society.”

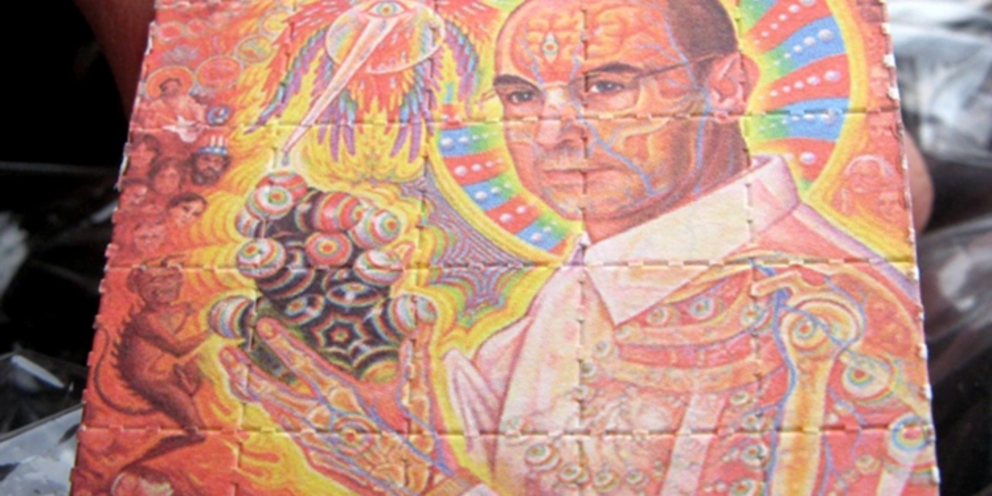

The study, “LSD, madness and healing: Mystical experiences as possible link between psychosis model and therapy model“, was authored by Isabel Wießner, Marcelo Falchi, Fernanda Palhano-Fontes, Amanda Feilding, Sidarta Ribeiro, and Luís Fernando Tófoli.