Monsanto’s foes are branching out

Call it the anti-Roundup dream team.

A coalition of attorneys, invigorated by their lawsuit representing cancer victims against Monsanto Co., is tackling the world’s most popular weedkiller on multiple fronts.

They are veteran environmental attorney and political scion Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.; Aimee Wagstaff of Andrus Wagstaff LP in Lakewood, Colo.; Michael Miller of the Miller Firm LLC in Orange, Va.; Michael Baum and Brent Wisner of Baum Hedlund Aristei Goldman PC in Los Angeles; and Robin Greenwald of Weitz & Luxenberg PC in New York.

Their weapon? A glimpse at decades of Monsanto’s internal deliberations on glyphosate, the main ingredient in Roundup herbicide. The attorneys have spent the last several months poring over hundreds of confidential documents they say show that the company actively worked to downplay the cancer risk for glyphosate. The plaintiffs in the high profile multi-district litigation (MDL), being heard in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, allege that Monsanto’s Roundup caused their non-Hodgkins lymphoma, a relatively common cancer of the blood.

They are now extending to another legal challenge. On June 20, they joined other attorneys in filing a complaint that accuses the company of falsely advertising that glyphosate works by targeting an enzyme that is not found in people or pets. They are teaming up with another law firm that is building a name on suing food companies for making such claims.

The attorneys have also weighed in on California’s decision to list glyphosate as a carcinogen under the state’s Proposition 65 law, which goes into effect July 7, and provided information to members of the European Parliament to sway decision-making on the herbicide.

The zeal with which the firms are taking on Monsanto—fueled, Kennedy said, by the troubling information culled from the documents—is rare in private practice, he told Bloomberg BNA.

“I’ve never seen private attorneys so energized against a defendant,” Kennedy, whose Hurley, N.Y.-based firm Kennedy & Madonna LLP is working with Baum Hedlund on the litigation, said. “Everybody is cooperating so well, we’ve created a team.”

Since March, the lawyers have successfully unsealed a trove of emails, letters and studies intended to inject doubt into the process by which Roundup earned its Environmental Protection Agency approval. They suggest that Monsanto’s scientists ghost-wrote studies that cleared glyphosate of its cancer-causing potential; that the company tried to enlist EPA staff to shut down an investigation into the herbicide; and that officials hired a scientist in 1985 to persuade EPA regulators to change its decision on its cancer classification for glyphosate.

Monsanto has denied these allegations, and the judge presiding in the case also has panned the attorneys for trying to unseal documents not directly relevant to the case, calling the move a “PR campaign” at a May 11 hearing.

Injury Lawyers as ‘Private AGs’?

People seeking to sue over Roundup exposure may now be more inclined to approach the firms, Wisner of Baum Hedlund told Bloomberg BNA.

“We’ve all had a chance to see what’s behind the curtain,” he said. “We bring a lot of institutional knowledge to the litigation.”

Since its introduction to consumers in 1974, Roundup has helped revolutionize farming practices, allowing growers to control weeds more efficiently and boost agricultural productivity. But concerns over use with genetically-engineered crops, the chemical’s presence in foods, and its role in fostering glyphosate-resistant weeds have left environmentalists skeptical.

Nonprofits have been suing the EPA and other federal agencies for failing to properly regulate glyphosate since the 1990s.

“The problem is so big, it’s creating opportunities left and right,” Adam Keats, a senior attorney with the Center for Food Safety, told Bloomberg BNA.

Regulatory bodies around the world, including the EPA, have backed findings showing that Roundup has low toxicity. But a contested 2015 finding from the International Agency for Research on Cancer that glyphosate is a “probable” carcinogen created an upwelling of cases from consumer protection and personal injury firms, many of which have been consolidated in the Northern District of California MDL.

These firms have deeper pockets—and less to lose—than environmental nonprofits fighting an agricultural giant, Keats said.

“We don’t have the same resources that law firms have; therefore, we pick and choose what we challenge,” he said. In seeking to reform the regulatory process, “we’re less subject to litigation tactics that would bleed us dry.”

When government agencies are reluctant to change their practice, consumer protection lawyers serve as vigilantes against weak regulation, Wisner said.

“I think that these [attorneys for] consumer fraud cases, for better or worse, were effectively becoming private attorney generals,” he said.

Suit Is Frivolous, Says Monsanto

The attorneys’ latest complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin, pushes back against one of the company’s claims.

Glyphosate kills weeds by inhibiting an enzyme essential for keeping plants alive. The chemical disrupts the pathway that the enzyme, 5- enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP), takes to process amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

Animals don’t process amino acids through the same pathway as plants. But bacteria, including the microbes that populate mammals’ guts, do. Recent research has found that human intestinal flora can affect the immune system, allergies, and even behavior. Therefore, Monsanto cannot declare that “glyphosate targets an enzyme found in plants but not people or pets,” the plaintiffs say.

SImilar “enzymatic pathway” arguments against Monsanto have failed in the past. Federal courts in New York and California dismissed cases when plaintiffs sought relief in the form of court-ordered label changes. The cases were thrown outbecause one of the nation’s pesticides laws, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act, dictates what information makes it on pesticide labels and pre-empts any injunctive relief claims.

The current action does not seek label changes. Instead, it seeks to compensate consumers who bought Roundup under the representation that the product does not affect human health, Kim Richman, an attorney with the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Richman Law Group, told Bloomberg BNA.

The Richman Law Group has sued several food and tobacco companies for making false and deceptive claims on their products. They have gone after General Mills for calling Nature Valley granola bars “natural” despite the presence of glyphosate residues, and RJ Reynolds Co. for implying that their brand of American Spirit cigarettes are healthier and safer than other brands.

In the Monsanto challenge, Richman said he wants to draw attention to glyphosate’s “real and most pervasive effect — weakening the human gut biome.”

“The public has been misled on this point, and it must be addressed,” he said.

Monsanto is confident the challenge will go nowhere.

“These are frivolous lawsuits without any merit. We will defend the Company vigorously, and we are confident we will prevail,” spokesman Sam Murphey said in an emailed statement.

The match between Richman and the lawyers in the Non-Hodgkins lymphoma MDL is a natural one for the anti-glyphosate crusaders.

“We’re bringing the science, he’s bringing his world class knowledge of consumer fraud,” Kennedy said.

David v. Goliath

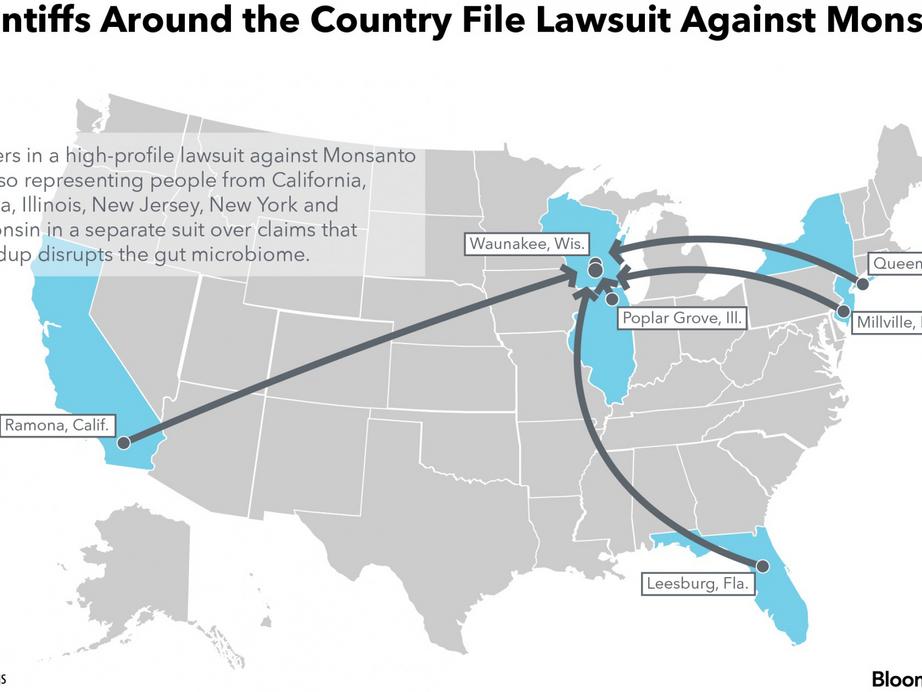

Richman has also sued Monsanto in D.C. District Court, as well as in Illinois federal court, over the company’s claims that Roundup doesn’t affect humans. In the latest complaint, the attorneys represent plaintiffs from Illinois, New York, Wisconsin, California, New Jersey and Florida, kicking off a nationwide class-action suit to recover monetary damages.

It’s Richman’s latest “big tent” approach in bringing together firms and groups taking on glyphosate from different angles: from consumer deception to public health.

Rather than having competing actions filed in different corners of the U.S., Richman said, his law group is coordinating attorneys across the country and across various practice areas.

This is “all in an effort to file together against a Goliath and bypass an otherwise complicated MDL process, which can often waste valuable judicial resources and delay available relief,” he said. The group used a similar tactic in lawsuits against Quaker Oats and General Mills.

The MDL process is triggered by the Judicial Panel on Multi-District Litigation (JPML), a panel of judges that meet six times a year to consolidate complaints across the country into a single court, allowing the process of collecting evidence to play out in that court before a trial begins in the jurisdiction of origin. The judges centralize these cases to avoid duplication, prevent inconsistent pretrial rulings, and save money.

But the MDL process can also be complicated, delaying relief and inviting some firms to take advantage of the system in a way that does not serve the lead plaintiffs or classes they seek to represent. The JPML may unwittingly disenfranchise the plaintiffs or classes by centralizing the cases far from their chosen jurisdiction, Richman said.

Instead of triggering an MDL, he said, the attorneys are able to self-organize and create a “mini” MDL. Avoiding the traditional process, when possible, reflects an emphasis to place plaintiffs and classes “before control and power,” Richman said.

The choice of the Wisconsin court is a deliberate one. The court has a reputation for quickly moving cases off the docket, Kennedy said.

Although these mini MDLs generally benefit plaintiffs, they also sidestep the neutral decision-maker in the MDL panel, said Andrew Bradt, an assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law who studies the MDL process. Both plaintiffs and defendants like to “shop” for the best court, which can lead to gamesmanship and inefficiency in the legal system.

“This is forum shopping on steroids,” he said.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.