Durrington Shafts: is Britain’s largest prehistoric monument a sonic temple?

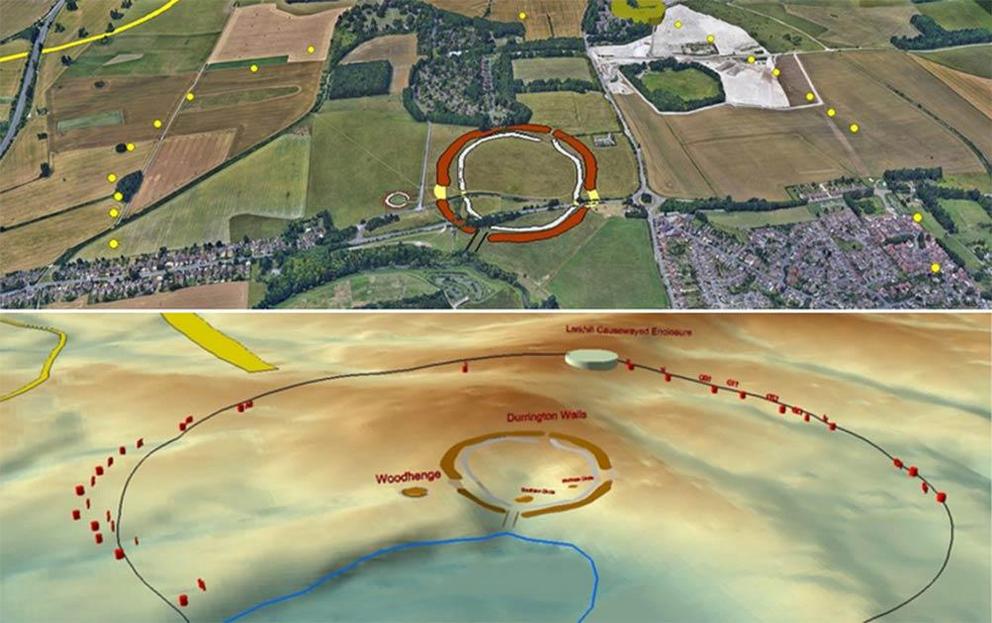

Maps of the extensive Neolithic structures show the new Durrington Shafts feature dwarfing all other ancient developments.

The recent discovery of an enormous ring of cylinder-like pits, each approximately five meters deep and 10 meters in diameter (16.5 by 33 ft), found to surround the henge enclosure of Durrington Walls in southern England, is set to become one of the greatest enigmas of British archaeology. With a maximum diameter of 2.31 kilometers (1.44 miles), this huge circular feature, to be henceforth known as Durrington Shafts, is now officially the largest prehistoric monument of its kind anywhere in the world. The fact that it is located just 3 kilometers (2 miles) from Stonehenge only adds to the mystery.

One of the most iconic images of the British Isles, Stonehenge.

One of the most iconic images of the British Isles, Stonehenge.

So far 20 of a suspected 50 pits have been identified using remote sensing techniques, although as yet only a handful have been explored. When they were constructed remains unclear. Their position around Durrington Walls , which in its present form belongs to the Late Neolithic period, offers dates in the region of 2670-2550 BC ( Gaffney et al, 2020 ), although there are indications that some of the pits could be older. Before the construction of the enormous earthen bank around Durrington Walls its central enclosure was surrounded by around 300 gigantic posts placed in a circle 440 meters (1445 ft) in diameter ( Bartos, 2016 ). Each year, at the winter solstice, people from all over southern England are thought to have descended on Durrington Walls to take part in feasting on a grand scale ( Craig et al, 2015 ).

So what then can we determine about Durrington Shafts? The first point of note is that of the 20 pits located so far almost all of them seem bunched into two distinctive arcs. Those on the southern side are on a much wider arc than those on the northern side. Why is this? Terrain, of course, could have been a factor in their placement, although what if the pits were never meant to be a perfect circle. What if they conformed to a different design altogether?

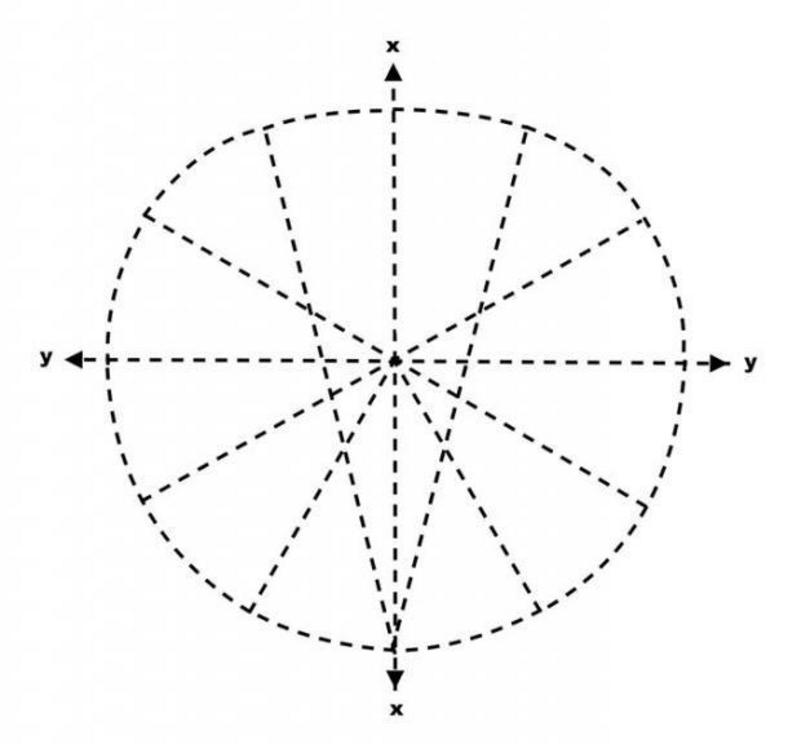

Type D Flattened Circle

Scottish engineer Professor Alexander Thom (1894-1985) surveyed around 250 stone circles in the British Isles and realized that not all of them were perfect circles. He recorded elliptical stone settings, egg-shaped stone settings, as well what he called flattened circles. What he referred to as a Type D flattened circle was seen to resemble the overall layout of the Durrington pit circle. So, using the positions of the 20 known shafts 17 were quite easily matched to Thom’s Type D flattened circle design.

Type D flattened circle – Alexander Thom‘s Type D flattened circle found in the construction of stone circles in the British Isles.

Type D flattened circle – Alexander Thom‘s Type D flattened circle found in the construction of stone circles in the British Isles.

The resulting overlay revealed something of potential significance. The y axis of the flattened circle targeted the center of Stonehenge at an angle of almost precisely 63 degrees. The geographical distance between the center of Durrington Shafts flattened circle and the center of Stonehenge was found to be approximately 3.16 kilometers (1.96 miles), and whether by accident or design this could be divided into 72 equal parts, each 144 feet in length.

Even though it might be argued that the concept of British measurement the ‘foot’ was unknown in the Neolithic age , it is a curious fact that the radius of the so-called Aubrey Holes , a circle of 56 chalk pits that surround the current Stonehenge monument, which once contained either wooden posts or bluestones, is 144 feet ( Peake, 1945 ). In other words, the radius of this circular feature, created as early as 3000 BC, is exactly 1/72 nd the distance between the center of Durrington Shafts and the center of Stonehenge.

Even further use of the same unit of length can be found at Woodhenge, a Neolithic monument lying immediately south of Durrington Walls and made up of six concentric rings of wooden posts. The maximum diameter of its outermost ring, composed of 60 posts, was found to be 144 feet ( Kendrick & Hawkes, 2018 ). Even more significant is that Durrington Walls’ is itself 440 meters (1443 feet) in diameter, extraordinarily close to 10 units of 144 feet, suggesting a “true” diameter of 1440 feet.

Overlay of Type D with Durrington Shafts. Caption: Thom’s Type D flattened circle overlaid on the positions of the Durrington Shafts (marked in red). Note the extension through the y axis west-southwestwards to the center of Stonehenge.

Overlay of Type D with Durrington Shafts. Caption: Thom’s Type D flattened circle overlaid on the positions of the Durrington Shafts (marked in red). Note the extension through the y axis west-southwestwards to the center of Stonehenge.

Grooved Ware Culture

Outside the Stonehenge landscape there is further evidence for the use of a unit of length equaling 144 feet. For instance, on the Orkney Mainland, off the north coast of Scotland, the circular earthen bank surrounding the Stones of Stenness, a stone circle built circa 3100 BC, has a diameter of 144 feet. As distant as the Orkney Isles might seem from the Stonehenge-Durrington landscape of southern England, there exist direct links between the megalithic cultures at both locations.

A very distinctive type of pottery found at both Stonehenge and Durrington Walls is Grooved Ware . This was first produced by the megalithic culture of the Orkney Isles around 3000 BC, and was thereafter carried southward into other parts of the British Isles. What is more, there is an even closer link between Durrington Walls and the Orkney Isles, for very recently a distinctive Grooved Ware incense cup was found during excavations at an important archaeological site on the Orkney Mainland known as the Ness of Brodgar. Only four other examples are known and all of these were found at Durrington Walls. The Stones of Stenness are located just 400 meters away from the Ness of Brodgar , so the fact that the same unit of length is found both on the Orkney Mainland and in the Stonehenge-Durrington landscape seems unlikely to be coincidence. It seems reasonable to suggest that the Grooved Ware culture carried with them knowledge of this unit of measure as they gradually spread southward.

Grooved Ware – Caption: Reproduction of a Grooved Ware pot found at the Ness of Brodgar excavations on the Orkney Mainland.

Grooved Ware – Caption: Reproduction of a Grooved Ware pot found at the Ness of Brodgar excavations on the Orkney Mainland.

Who Built Durrington Shafts?

Is it possible that the Grooved Ware culture were responsible for the construction of Durrington Shafts? Let’s examine the evidence. By circa 2670-2550 BC, when the pits were being dug, three distinct cultures were present in southern England. The first was the Grooved Ware culture, which originated in the Orkney Isles. The second group was an indigenous people associated with the long barrows built circa 3800-3500 BC, several of which were to be found in the Stonehenge-Durrington landscape.

These structures functioned as communal places of the dead where interments were made and communication with the ancestors became possible. From the extensive work undertaken by Maria Wheatley it would seem that the long barrow people were small in stature, no more than five to five and half feet tall, with long ( dolichocephalic) skulls. From remains found alongside their burials it would seem they practiced a shamanistic tradition in which females played a lead role.

A third influence that almost certainly came to bear on the Late Neolithic world of Stonehenge and Durrington by 2600 BC was the Beaker People , who first introduced bronze items to Britain. Coming from the Iberian Peninsula (although with origins far to the east on the Russian steppe), they buried their dead in a fetal position alongside a distinctive type of decorated beaker pot, hence their name. Burials were then covered over with earthen mounds called round barrows or tumuli. There were once hundreds of these barrows in the Stonehenge landscape, and many still survive today.

The most likely culture responsible for the construction of Durrington Shafts was the Grooved Ware culture. Pottery found in one of the pits suggests they date to the Late Neolithic period, and not to the subsequent Bronze Age ( Gaffney et al, 2020 ). What is more, there is evidence that the Grooved Ware people engaged in monumental construction projects elsewhere in Britain.

This includes Danes Dyke, an enormous linear ditch 30 meters (98.5 ft) in depth and width, and 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) in length, which cuts off five square miles of seaward headland at Bridlington in North Yorkshire. Although usually attributed to a much later age and said to be defensive in nature, when excavated in 1879 stone tools were found in its ditch dating to no later than the early Bronze Age ( Hobson, 1924 ). This fact, along with others as well, make it likely that Danes Dyke was the creation of the Grooved Ware culture, which thrived in the Bridlington area around the same time as the construction of Durrington Shafts.

Although a 4-kilometer long entrenchment cut into the chalk bedrock in no way resembles huge cylindrical pits dug into the earth, it does indicate the sophisticated level of engineering employed by the Grooved Ware culture, making them the most likely candidates for the construction of Durrington Shafts.

The Stones of Stenness on the Orkney Mainland. Dating to circa 3100 BC, it is thought to be the oldest stone circle in the British Isles.

The Stones of Stenness on the Orkney Mainland. Dating to circa 3100 BC, it is thought to be the oldest stone circle in the British Isles.

Is Sound the Key?

Having established that the Grooved Ware culture were most likely responsible for the construction of the shafts, the question remains as to their purpose. For instance, could the pits have been used as dumps for the disposal of human refuse? This seems unlikely as those investigated so far were found to be devoid of anything other than a few flint flakes and, in one instance, a few fragments of pottery. They are unlikely also to have been used as cisterns since the local chalk bedrock is porous. Most likely the shafts were functional in nature. Yet how exactly? The answer may lay in their shape with one end open and the other closed, making them suitable as resonant chambers.

Stonehenge Experiments

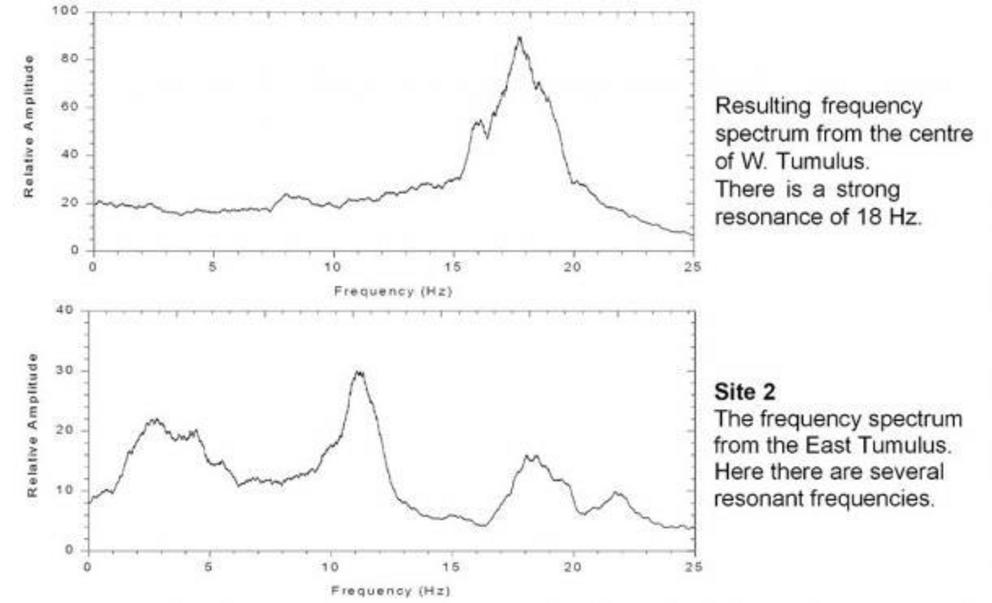

Supporting the idea that the ring of pits at Durrington might have functioned as sound resonators is work carried out in 1999 by chartered engineer Rodney Hale in the Stonehenge landscape. At two round barrows (Amesbury 43 & 47) he used an induction coil interacting with the earth’s magnetic field to measure the presence of low frequency activity. Resulting signals were amplified and recorded. Each tumulus was found to produce oscillatory readings showing the constant presence of ultra-low frequency (ULF) sub-audible sound vibrations in the range of 18 Hz in the first tumuli and 11 Hz in the second.* The amplitude of the sound could be increased by stamping on the ground, although Hale suspects that this could be quite easily affected by other factors including wind blowing across the surface of the tumulus.

Stonehenge tumuli vibrations. Waveforms showing ultra-low frequency activity recorded by Rodney Hale during an experiment in 1999 at two round barrows in the Stonehenge landscape.

Stonehenge tumuli vibrations. Waveforms showing ultra-low frequency activity recorded by Rodney Hale during an experiment in 1999 at two round barrows in the Stonehenge landscape.

Tests showed that the ULF activity was present everywhere on the barrows, yet dropped off sharply around 30 centimeters (a foot) from the edge of the mounds. What these trial tests implied was the existence in each of a large hollow cavity or internal structure easily able to generate sound. Was it possible that other tumuli in the Stonehenge landscape had similar internal structures? Had this been part of their original design, to generate low frequency sound?

The resonant frequency of the pits making up Durrington Shafts was found to be in the range of 10 to 15 Hz, low enough to produce not only very low frequency activity, but also infrasound. This has been linked with everything from the creation of altered states of consciousness in human subjects to a go-to explanation for paranormal experiences such as the feeling of presences and the seeing of ghosts.

ULF activity as well as infrasound has been detected in the underground chambers of the Great Pyramid in Egypt, suggesting that this might have been a factor in the architectural design of such monuments. It should be recalled that the Great Pyramid dates to circa 2600 BC, exactly the same time as Durrington Shafts. That its pits generated a similar frequency range adds weight to the idea that they too acted as sound resonators. If so, then how might this have been amplified? And more importantly, to what end?

Sonic Temple

Rodney Hale suggests that for the pits to be used as sound resonators the deliberate introduction of wind would have been necessary. Wind crossing the lip of a shaft would have invoked oscillations or vibrations, whilst air traveling to the bottom and back up again would have reinforced this process. The efficiency of such structures could have been enhanced still further by the creation of a roof-like structure with holes. The result would have been extremely deep sounds that were more felt or experienced than heard.

A Magnificent Chorus of Noise

The generation of sound vibration at such low frequencies would very easily have been carried on a sub-audible level through the earth in the same manner as seismic waves. This could have enabled communication between distant points, in particular features displaying the same resonant frequency range as the shafts themselves. As Hale makes clear, on windy days the shafts would have produced a magnificent chorus of noise that could have been detected across an extended distance.

In Britain it is usually the early part of winter that is the wettest and windiest time of the year, making it likely that this is when Durrington Shafts would have been at their fullest potential. A person in their vicinity with strong winds blowing may have experienced deep subliminal feelings from the resulting low vibrational sound. We may never know for certain how they interpreted this, or why it was important. However, there is evidence to suggest that the Grooved Ware culture were strongly focused spiritually on ancestor veneration and so perhaps this sound was considered a sign that the ancestors were returning to this world.

Sonic Pattern of the Universe

Proposing that Durrington Shafts functioned as an enormous sonic temple constructed within the Stonehenge landscape might seem far-fetched. Yet it is a fact that as far back as 1969 English Earth mysteries visionary John Michell (1933-2009), the author of various thought-providing books on the megalithic mindset, imagined Woodhenge as a giant Aeolian harp emitting unearthly sounds as wind passed through its concentric rings of wooden posts, each linked by a series of cords of varying lengths and thicknesses. In his words, Woodhenge “appears to have been a stringed musical instrument laid out according to the plan of the universe (Michell, The View Over Atlantis, 1969, 122).” For him the construction of the monument conformed to a “sonic pattern of the universe” known to the megalithic builders of Britain and rediscovered millennia later by Pythagoras and his followers.

Woodhenge monument, south of Durrington Walls, as it looks today. Did its rings of posts function as a generator of sound?

Woodhenge monument, south of Durrington Walls, as it looks today. Did its rings of posts function as a generator of sound?

Michell’s words now take on a new meaning in the knowledge that Woodhenge, being just a few hundred meters south of Durrington Walls, falls within the great circle defined by Durrington Shafts. It might also be no coincidence that the maximum diameter of Woodhenge’s outer ring of posts is 144 feet, the same unit of length defining not only the size of Durrington Walls but also the precise distance between the center of Durrington Shafts’ flattened circle and the center of Stonehenge. What then is the significance of this recurring distance? Why might the megalithic builders have been so interested in employing its use in the layout and placement of their monuments?

Schumann’s Resonance

The answer perhaps lies in the fact that the harmonic frequency of 144 feet is 7.85 Hz, meaning that the wavelength of 7.85 Hz, in other words its distance of travel from high pressure to low pressure back to high pressure again, is 144 feet. The first higher harmonic of 7.85 Hz is 15.7 Hz, corresponding with the resonant frequency range calculated in connection with Durrington Shafts in their role as sound resonators.

Perhaps not unrelated is the fact that the fundamental frequency of the Schumann resonance, the oscillation of the Earth’s atmosphere triggered most obviously by lightning flashes anywhere in the world, is itself 7.85 Hz. Even though the Schumann resonance is a radio frequency (RF) and not a sound frequency, the fact that its frequency corresponds with that of the 144 feet wavelength distance found in connection with Stonehenge, Woodhenge and Durrington Walls is curious indeed.

Are we seeing evidence here that the Grooved Ware culture were not only aware of sound frequencies, and the distance they travel to create one cycle of wavelength, but that they also, perhaps intuitively, became aware of the Schumann’s resonance? The evidence presented here would suggest the answer is yes. If so, then sound, and its relationship to the fundamental harmonics of the earth, might well be the key to understanding the greater functional purpose of prehistoric monuments such as Durrington Shafts, which, as John Michell surmised, could well have been deliberately attuned to reflect the “sonic pattern of the universe.”

*Thanks to Rodney Hale, Catherine Hale, Bob Trubshaw, Maria Wheatley, Graham Phillips, Debbie Benstead and Richard Ward.